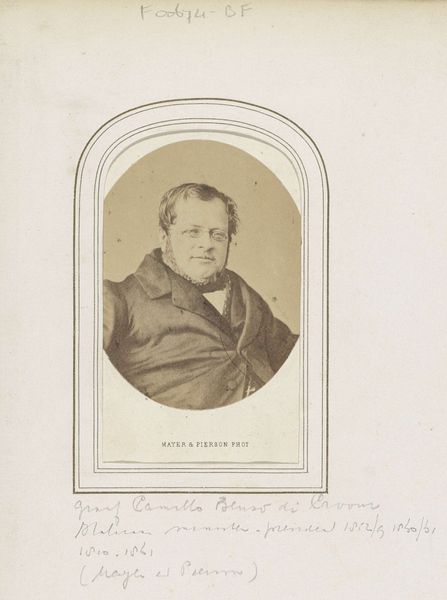

silver, print, daguerreotype, photography

#

portrait

#

16_19th-century

#

silver

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

daguerreotype

#

charcoal drawing

#

photography

#

pencil drawing

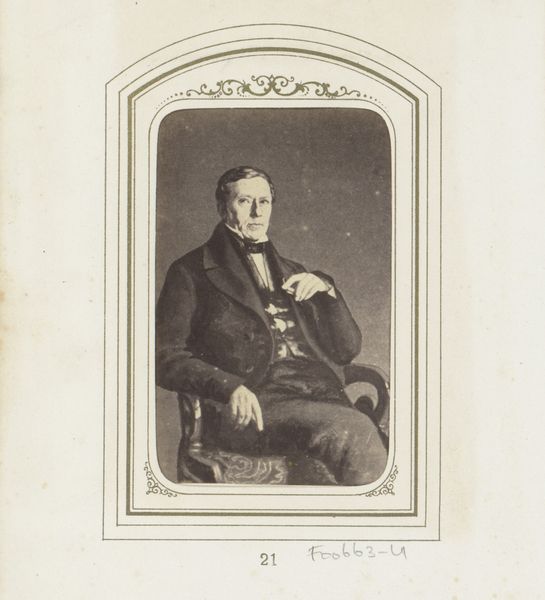

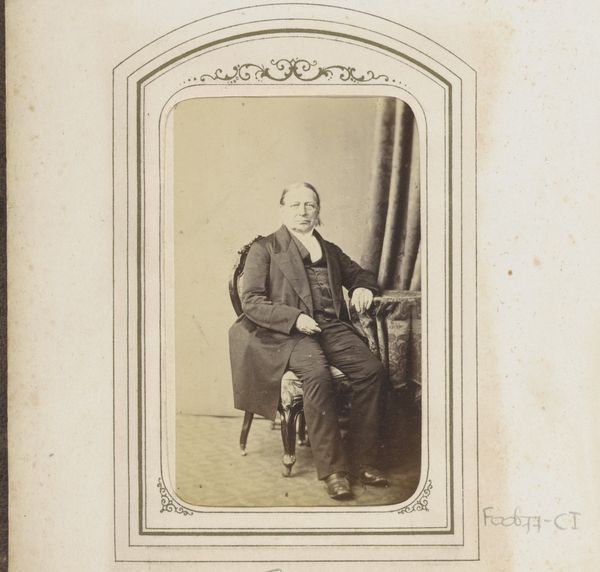

Dimensions: 8.4 × 5.5 cm (image/paper); 10.1 × 6.2 cm (mount)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Standing before us is "Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour," a fascinating piece from the 1860s. It's a photographic portrait, specifically a silver print daguerreotype. Editor: It’s strikingly…austere. There's something so controlled about the light, almost cold, despite the formality of his pose with his hand tucked into his jacket. The monochromatic rendering really reinforces that. Curator: Exactly! The medium itself – the daguerreotype – lends to that formality. In that era, photography was a technological marvel, and portraits like this became vital tools for projecting power and documenting important figures like Cavour. He was instrumental in the unification of Italy, and this image solidifies his presence in that historical narrative. How does the materiality speak to this construction of leadership, do you think? Editor: Well, you’ve got to think about the process. Silver print requires meticulous preparation, careful execution – much like statecraft itself. There’s a sense of alchemical precision here, mirroring the crafting of political image. It’s not a candid snapshot, but a carefully constructed presentation of authority through chemical processes and light manipulation. The labour behind its crafting clearly suggests an aura. Curator: Precisely. The daguerreotype freezes him in time, quite literally. Considering the socio-political upheavals happening at that very moment across Europe – revolutions, nationalistic fervor, and a drive for unification. He's centered in Italian identity building, his representation gains critical ideological heft and power when considering it was a portrait that, without a doubt, only reached the eyes of the elites. How might that exclusivity speak to how we reckon with figures like him now? Editor: Thinking about that audience…the material reality is that making portraits available via photograph expanded their reach exponentially when compared to painted portraiture of centuries past, democratising a genre and giving broader audiences direct access, with affordable photographs helping cement ideologies more easily among larger audiences, yet its precious material signals access nonetheless, thus re-entrenching historical disparities. Curator: And there’s the rub – technological advancement intersecting with social hierarchies and ongoing inequities. It's crucial that we unpack this complex weave. Any final reflections? Editor: Looking closely allows me to not just think about a historical figure or the artistic intention behind this representation, but of the means with which images cement narratives, as well as of those who historically wield power due to the sheer exclusivity linked to craftsmanship in materials like these.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.