print, ink, woodblock-print, wood

#

ink painting

# print

#

landscape

#

ukiyo-e

#

figuration

#

ink

#

woodblock-print

#

wood

#

watercolor

Dimensions: 8 3/8 × 5 13/16 in. (21.2 × 14.7 cm) (image, sheet, vertical chūban)

Copyright: Public Domain

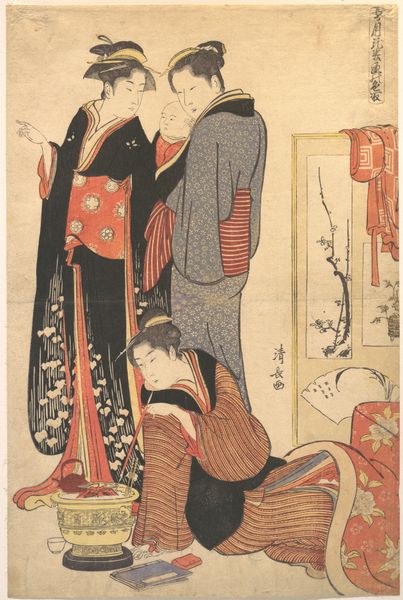

Curator: Well, this looks intriguing. Editor: Indeed. What we’re viewing is titled "The Ninth Month," a woodblock print in ink and color by Katsushika Hokusai, created around 1793. It's part of the collection at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. My first impression is that the piece feels intimate, domestic even, despite being a printed medium rather than a unique painting. There's a softness, a gentle elegance to the composition and line work. Curator: I agree about the intimacy. The choice of woodblock printing allows for the wide dissemination of such scenes, bringing glimpses into the lives of these figures, these refined commodities, into the hands of a broader public, and playing a crucial role in popularizing Ukiyo-e prints. The visible grain of the wood itself, even through layers of ink, speaks to its production and consumption. Editor: And it's interesting to consider the social function of prints like these. They depict courtesans and everyday life, effectively acting as visual documentation of contemporary culture but simultaneously shaping perceptions and reinforcing social hierarchies through their distribution and imagery. Curator: Absolutely. The material process inherently shapes its social role. Take the chrysanthemums, for instance. We tend to see these floral elements as mere background details. But to the Japanese populace, they're symbols of longevity and nobility. The fact that these attributes are deliberately situated around people makes us question their social status, whether through hard labor or through their status of nobility. Editor: It's all deliberately curated by Hokusai and his production teams to not only capture a likeness but also transmit cultural values and subtly promote status. The arrangement also implies narratives. Are we witnessing a scene of companionship, service, a fleeting interaction within a larger social space? It encourages speculation, it gives viewers a peek into a world just out of reach for some, aspirational perhaps. Curator: Precisely, aspirational because there's a craft at play in producing such pieces, the artisan who must cut away all areas except for the lines. By using print rather than painting, a means of mass production that would have impacted what an artist in this era can truly produce. The value wasn't so much tied to what could have been created with ink, brush, and paper, but to how they managed and oversaw the making and production of these artworks, where their social impact might lay. Editor: Examining the social context and how production informs reception… That has truly deepened my understanding. Thanks for illuminating those processes. Curator: My pleasure, considering the materials and mode of creation provides rich insights.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.