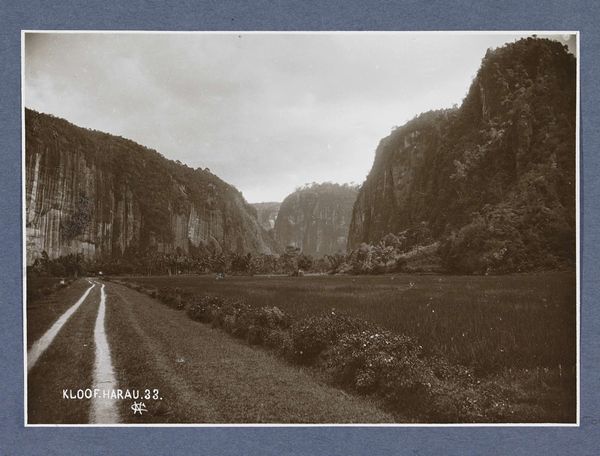

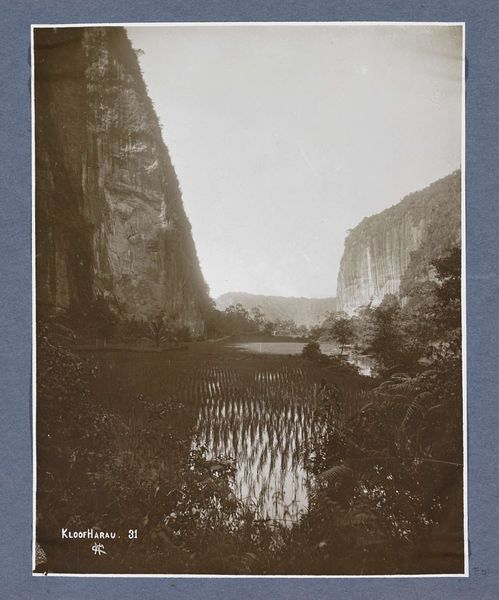

Kloof van Harau op Sumatra met op de voorgrond drie jongens c. 1900 - 1920

0:00

0:00

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

orientalism

#

gelatin-silver-print

Dimensions: height 189 mm, width 290 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

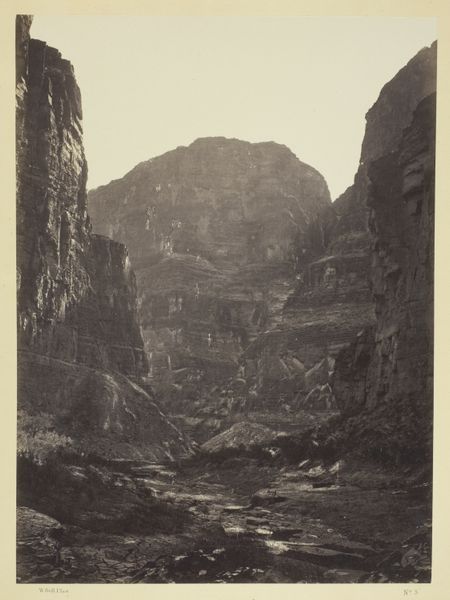

Curator: Standing before us is a gelatin silver print entitled "Kloof van Harau op Sumatra met op de voorgrond drie jongens," which translates to "Harau Ravine in Sumatra with three boys in the foreground." It’s attributed to Christiaan Benjamin Nieuwenhuis and dates from about 1900 to 1920. Editor: Wow, it feels… colossal. The sheer scale of those cliffs – they dwarf everything, even with the houses in the distance! It's as if nature is making a statement, a powerful "Here I am!" and those little human figures feel like tiny players in a giant landscape play. Curator: That feeling of overwhelming scale is certainly central to the photograph's impact. Nieuwenhuis captured this scene at a time of growing European interest in and engagement with Southeast Asia, aligning with the aesthetics of Orientalism, emphasizing the exotic and monumental aspects of these regions. The medium of photography itself also became a crucial tool in shaping and disseminating such perspectives, not always innocent in intent. Editor: Knowing that context gives me chills! It's beautiful, sure, but also kind of…exploitative? Those boys are framed so deliberately against that vastness; the romantic framing almost erases any individuality they might have. It’s a gorgeous visual, yet I feel unease. It's that photographer, inserting his frame, that kind of dictates how others later look back at these lands! Curator: Your response resonates with the photograph's complex relationship to colonial visual culture. These types of landscape depictions also played a part in attracting economic activities to these areas: exploiting them for agriculture, resources, other industries and ultimately transforming indigenous life there. Editor: Looking again, it’s not just visual, but a bit manipulative too, if you catch my meaning! Curator: It’s crucial to acknowledge this tension when looking at such images, to consider their active role, rather than passive reflections, of that period’s global power dynamics. Nieuwenhuis was deeply involved in agriculture. Editor: Food for thought indeed! Well, my initial feeling of awe hasn’t completely disappeared. It just got a whole lot more complicated now! Thanks for making it click, that looking isn't always so straight forward. Curator: Likewise. Recognizing these multiple dimensions enhances, rather than diminishes, the photograph's power to provoke critical engagement with the past.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.