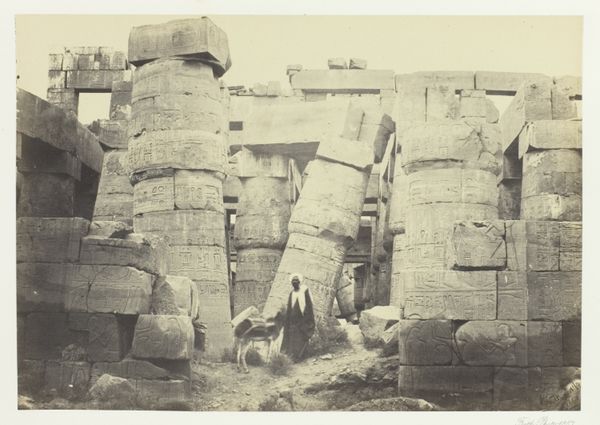

photography, sculpture, gelatin-silver-print

#

landscape

#

ancient-egyptian-art

#

outdoor photography

#

photography

#

sculpture

#

gelatin-silver-print

Copyright: Public Domain

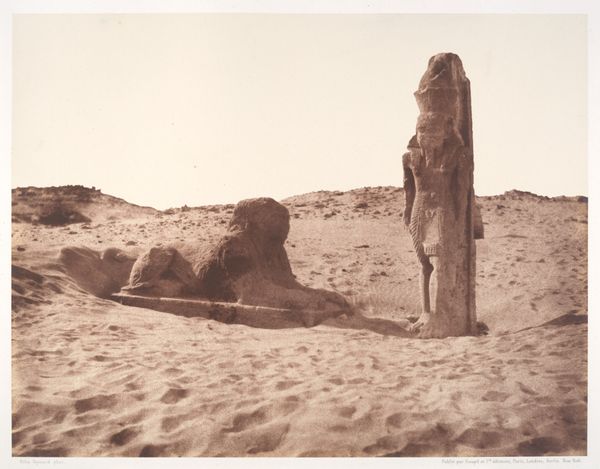

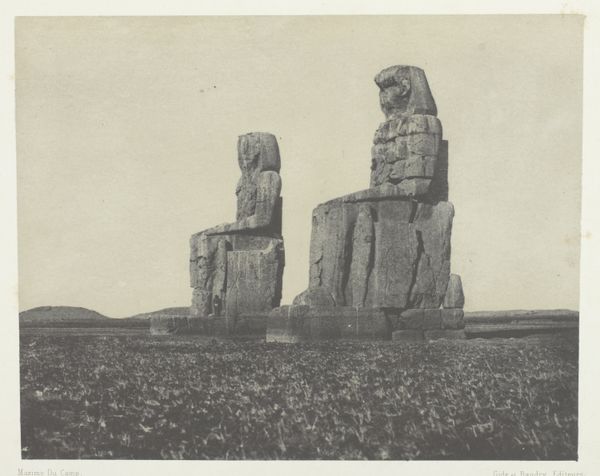

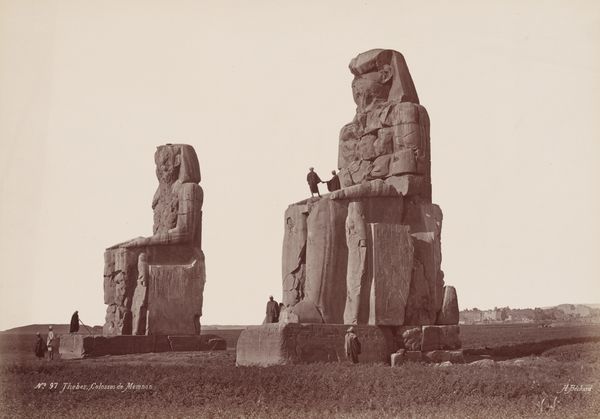

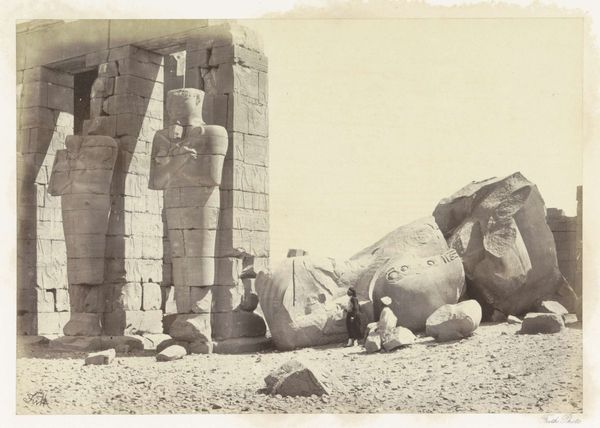

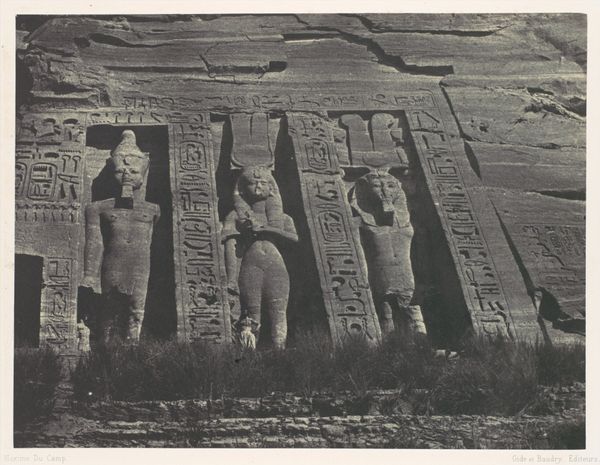

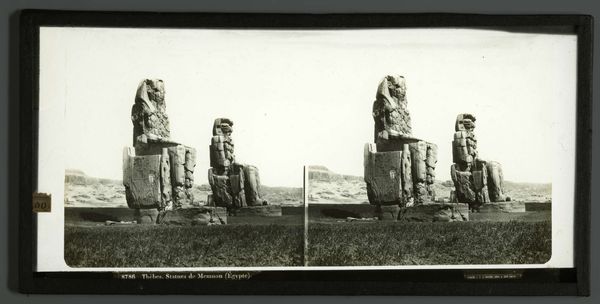

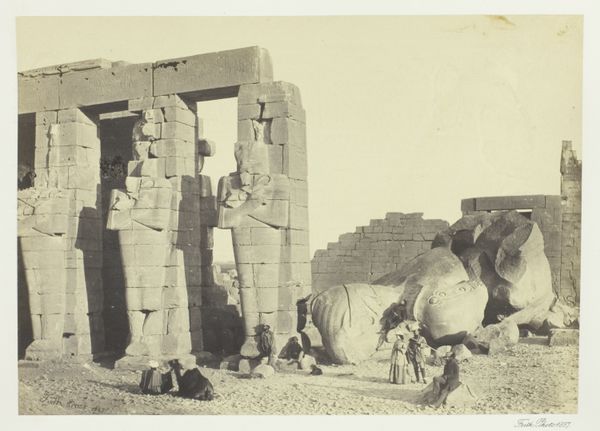

Curator: Francis Frith's gelatin-silver print, “Colossi and Sphynx at Wady Saboua,” created in 1857, offers us a fascinating glimpse into 19th-century Egypt and its encounter with early photographic documentation. Editor: Wow. The scene has a haunting serenity. It's almost like a dream, a mirage shimmering on the horizon. Are those whispers of wind I hear? Curator: It is an evocative image. Frith was one of the first photographers to venture to Egypt, part of a larger colonial project of documenting and, in some ways, possessing its history and monuments. The photography, exhibited in European halls, created an easy understanding for how colonizers would see a world they dominated. Editor: That makes sense. I guess it feels a little bittersweet knowing what happened next. But even so, look at how he’s captured the light; the sheer scale of the statues half-submerged in sand... It's just... immense. Does anyone know why these monuments are at that spot? Curator: Wady Saboua was the site of an important temple built by Ramses II. The temple and these sculptures would have been integral in demonstrating Pharaonic power and the divinely ordained rule of the pharaoh. In his travels, Frith traveled widely, photographing temples, cities, and landscapes, constructing for a European audience an image of the “Orient.” Editor: There’s something powerful in the contrast between that history, that original assertion of power, and the quiet way nature is reclaiming everything here. Like nature, even over the monuments humans built for permanence. What did people think back in England, seeing scenes like this for the first time? Did they sense any of that? Curator: For many, images like these reinforced a narrative of a 'lost' or 'sleeping' civilization that needed European intervention and guidance. The technical aspects of the photograph itself—the sharp details rendered through the gelatin-silver print—would've offered an undeniable sense of ‘reality.’ Editor: Reality, processed and framed by the photographer. You know, even with the problematic colonial undertones, I can't help but feel a strange sort of beauty, seeing this moment in time captured. All that we know now about these colonizing ways seems to blend away into these serene scenes. Curator: It is this very complexity that makes the photograph resonate; its ability to carry a message, and convey something beautiful, without us really even grasping at the depths of that which the photograph tries to tell. Editor: Absolutely. It’s a good reminder that images, like these old colossi, hold so much more than what meets the eye. A single picture does paint a thousand words but many interpretations and insights will give context to it, both good and bad.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.