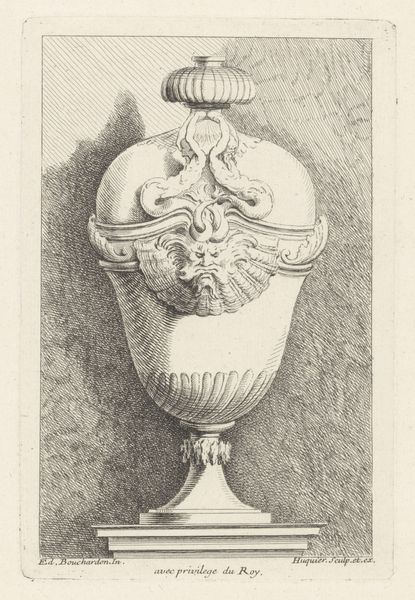

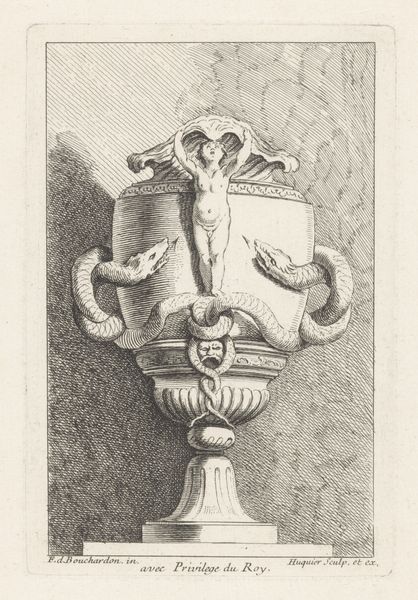

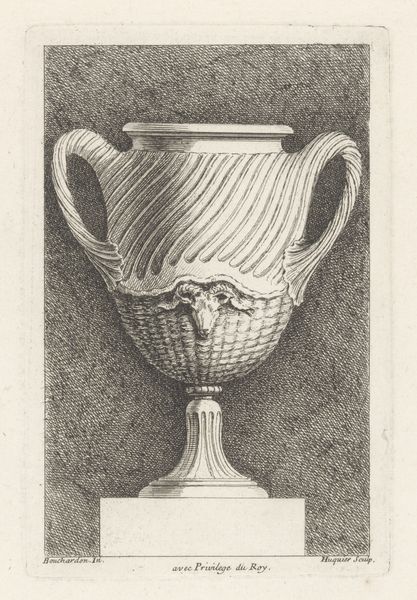

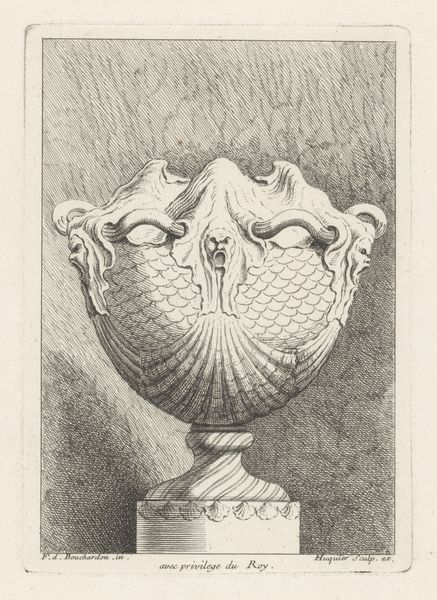

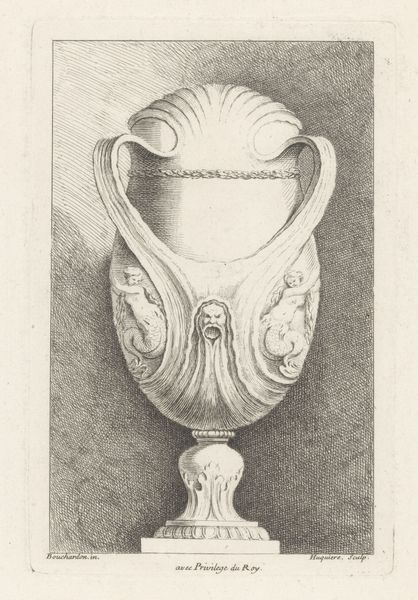

print, engraving

#

allegory

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

caricature

#

classical-realism

#

decorative-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 198 mm, width 129 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

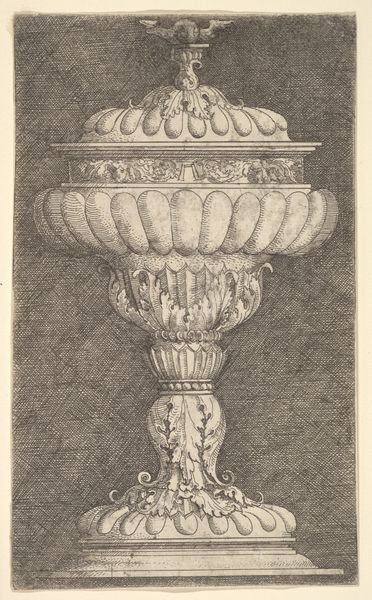

Editor: Here we have Gabriel Huquier's print, "Vaas met Venus in een kar getrokken door zwanen," created sometime between 1729 and 1737. It's an engraving of a vase depicting Venus in her chariot. The intricacy of the engraving is what first strikes me. What stands out to you? Curator: What intrigues me is how this engraving reproduces an object—likely intended for aristocratic consumption. Think about the division of labor inherent in its production: a designer like Bouchardon conceiving the vase, artisans crafting the original object perhaps in precious materials, and then Huquier translating it into a widely distributable print. Editor: That’s interesting. I hadn't thought about all the hands involved. So, is the print just a promotional tool then? Curator: Not just. Consider the social context. During the Baroque period, these images circulated among a growing class of consumers. Engravings like this made luxury accessible, albeit visually. It fueled desires, showcased taste, and propagated design ideas. It democratizes art, or at least the *idea* of art. But also, who profits most from its production? Editor: The person who owns the press, presumably. Are you saying this image highlights a class divide? Curator: Precisely! The detailed execution—the swirling lines, the allegorical figures—disguises the underlying economic structure that enables its existence. It makes you wonder about the working conditions of the engravers themselves, doesn't it? And what was the cost of the copper used in the print? Editor: I see what you mean. I initially focused on the image, but thinking about it as a product of labor gives it a whole new meaning. Curator: Exactly. By analyzing the means of production and the materials themselves, we uncover the social relationships embedded within the artwork.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.