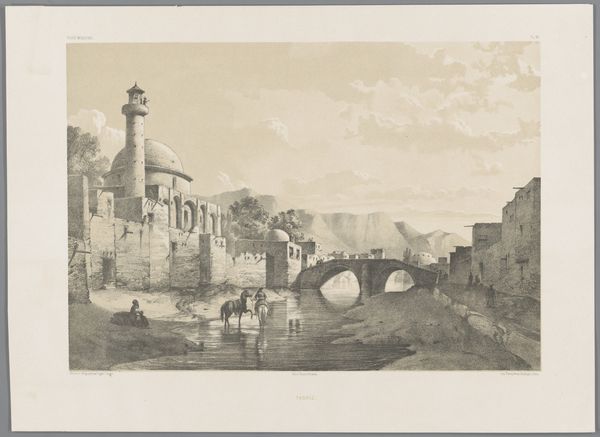

drawing, lithograph, print

#

drawing

#

lithograph

# print

#

landscape

#

orientalism

#

cityscape

#

islamic-art

Dimensions: height 266 mm, width 382 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

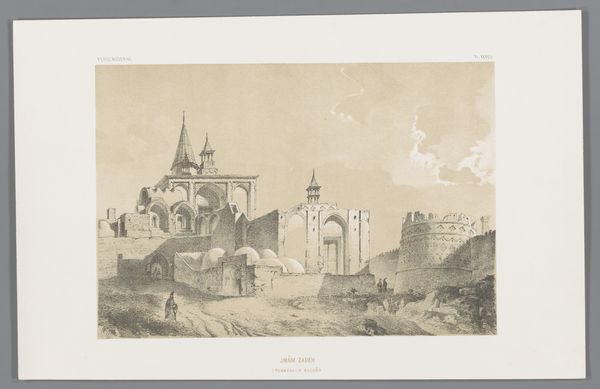

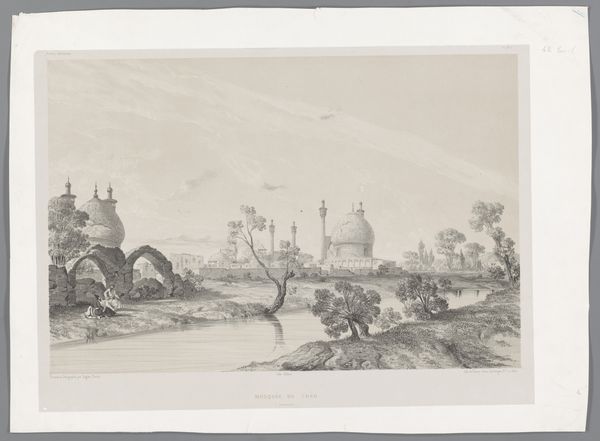

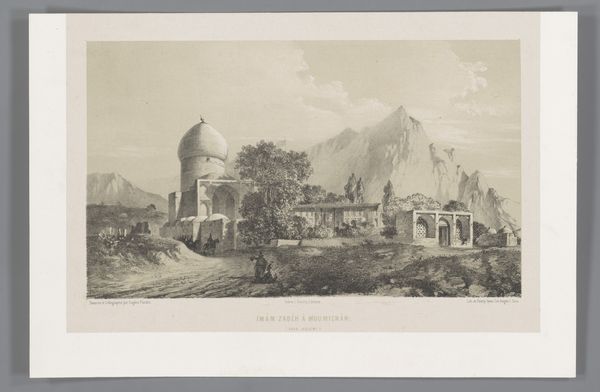

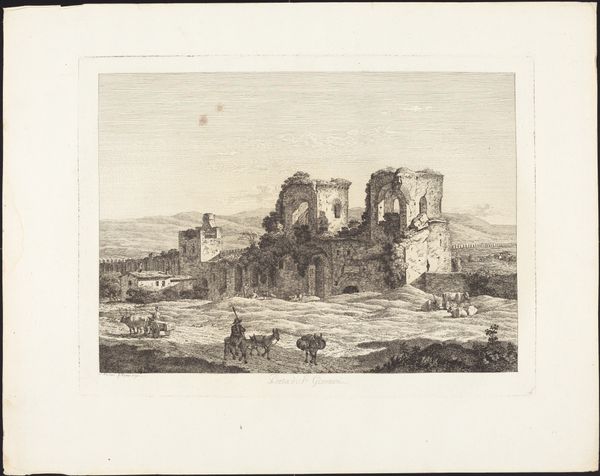

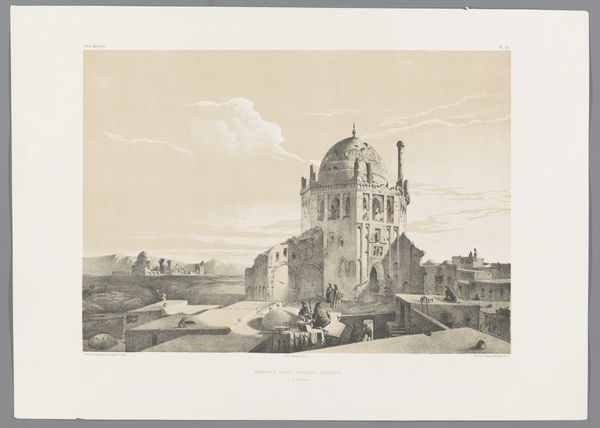

Curator: Today we're looking at Eugène Flandin's lithograph, "Graftombes in Qom," created between 1843 and 1854. It’s currently housed here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My first impression is one of solemn grandeur. The pale sepia tones create a somewhat melancholic, ethereal quality that sets a mood of contemplative reverence, as though capturing history itself fading slowly away. Curator: Exactly. Flandin's masterful rendering captures the silent narratives embedded in the architecture of the tomb structures. The pointed domes often symbolize transcendence and act as visual markers connecting the earthly and celestial realms. We should also note the impact of Orientalism on Flandin. Editor: Absolutely. This piece clearly evokes Orientalist aesthetics of that period; but beyond the artistic movement of the time, I’m drawn to the actual physical labor involved in crafting this image, turning a drawing into multiple printed copies. It also raises a number of questions about circulation, accessibility, and audience for such a piece, not to mention how Flandin himself was supported on such expeditions. Curator: Good points. And it’s relevant, as the cityscape theme invites a conversation on the power dynamics inherent in architectural representations of the ‘other’—an element intrinsic to this particular branch of landscape art. Look at the men gathered on the lower hill. They add both depth to the scene and context, in what looks like contemplation or rest. Editor: True. There’s also an underlying suggestion about their connection to the site – perhaps the building work and the significance behind it. These sepia lithographs offer a sense of accessibility through its reproduction method, enabling people to grasp the social implications related to cultural patrimony at that time. Curator: Yes, it presents itself not just as a representation of Islamic art but as a point of intercultural intersection, inviting interpretations rooted in collective historical memory, and also a colonial eye looking at it. Editor: It’s fascinating to consider the artwork’s status as a reproducible commodity carrying particular implications – both a means of artistic expression as well as evidence of artistic labor. Curator: Indeed. Its significance lies in its multiple layers of visual coding from symbols to its making process, leaving much to explore still today. Editor: Leaving us all to wonder what happened to the hands that toiled on creating these magnificent tombs, and on replicating Flandin’s artistry into the wider world.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.