drawing, print, ink

#

drawing

# print

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

ink

#

genre-painting

#

northern-renaissance

Dimensions: Sheet: 2 5/16 × 3 3/8 in. (5.9 × 8.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

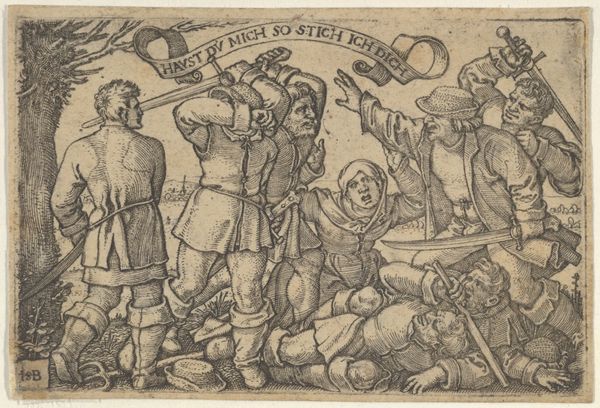

Curator: This drawing, "Farmers, from Das Bossenbüchlein," comes to us from Mathais Beitler, dating to somewhere between 1577 and 1587. Crafted using ink, it combines the mediums of drawing and print, offering a snapshot into life during the Renaissance. What are your immediate thoughts on it? Editor: Well, my initial feeling is one of somewhat stilted formality. There's a peculiar stillness to the figures and landscape, despite ostensibly depicting agricultural life. It feels less like a natural scene and more like a staged tableau, somehow. Curator: Indeed. It’s worth considering the role prints and drawings like this played at the time. This piece from Beitler served to instruct on various social classes and occupations. We're seeing farmers, but within a broader context of cataloging and, arguably, codifying social order. Who is seen working on the land? Who gets the spoils, if there are any? How do we define our social structures today, and are there links to what Beitler sought to achieve in the 16th century? Editor: It definitely reads that way, a visual taxonomy almost. Look at the detail in the man's garb compared to the woman. His feathered cap, his sword, his staff -- symbols of authority, even a certain masculinity. And there’s the gendering of labor, too: the woman carrying the basket, passively receiving perhaps, and the man seemingly directing, asserting. Can we connect this with the division of agricultural labor that’s persisted across time? Curator: Exactly. Beitler places them within an imagined hierarchy, reflecting contemporary attitudes towards labor and gender. What is equally interesting, and often missed, is how he subtly encodes rural spaces as somehow removed from the center of societal ‘progress.’ Even if the work done here quite literally feeds the engine. Editor: And the setting reinforces this separation. The quaint buildings, the rudimentary watermill. It all feels intentionally simplistic, perhaps as a way to other or essentialize the rural experience. Thinking about the watermill particularly: what part of this technology and the wider economic and social implications are left out of the rendering? It forces us to consider who these images served, and who benefitted. Curator: These details highlight the ways images, even seemingly straightforward genre scenes, carry embedded social and political ideologies. Images serve many masters and mistresses. Editor: So true. Analyzing artworks like this challenges us to excavate these often-unacknowledged layers, understanding how representation shapes our understanding of history. I’m leaving with new questions. Curator: It's been enriching to revisit this piece with fresh eyes, noting how historical artworks still spark debate and inquiry. The conversations always linger far longer than anticipated, wouldn’t you agree?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.