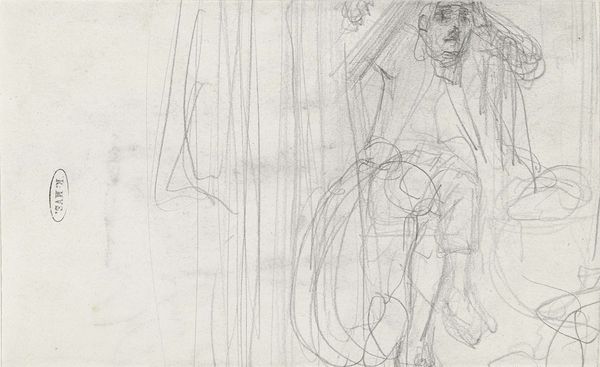

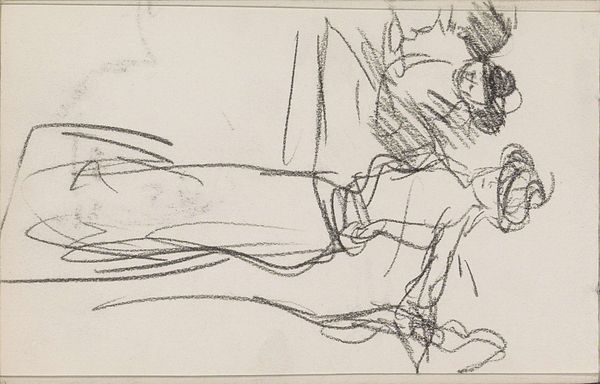

drawing, paper, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

figuration

#

paper

#

pencil

#

line

#

pre-raphaelites

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

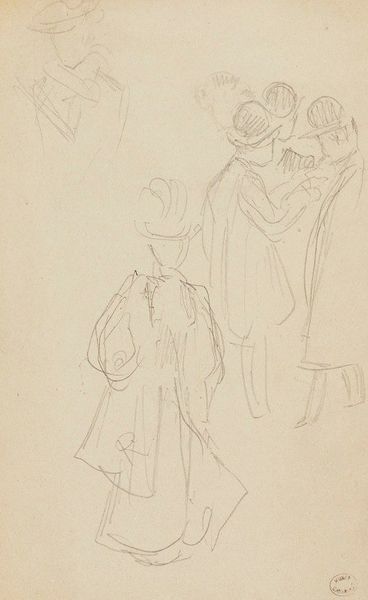

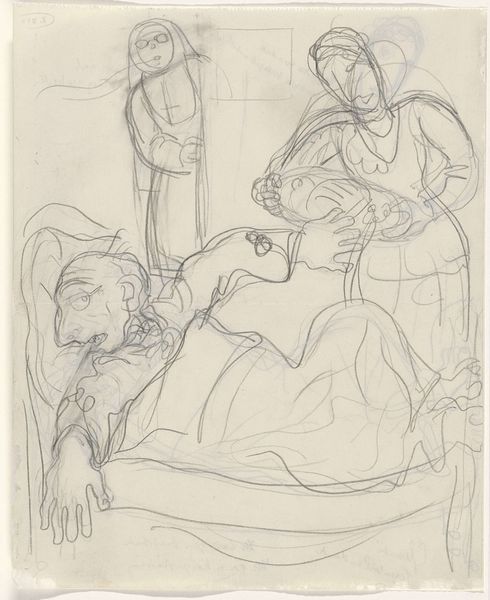

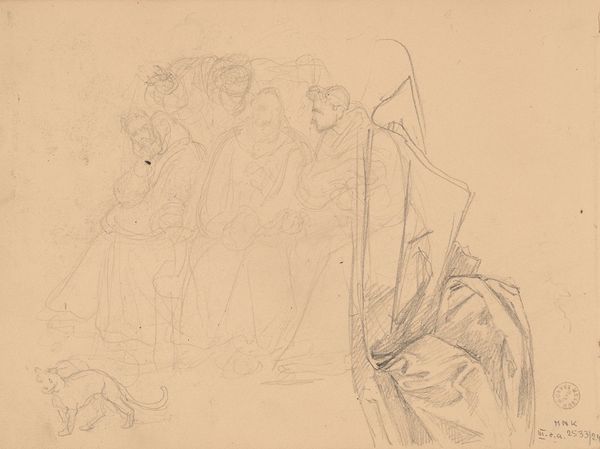

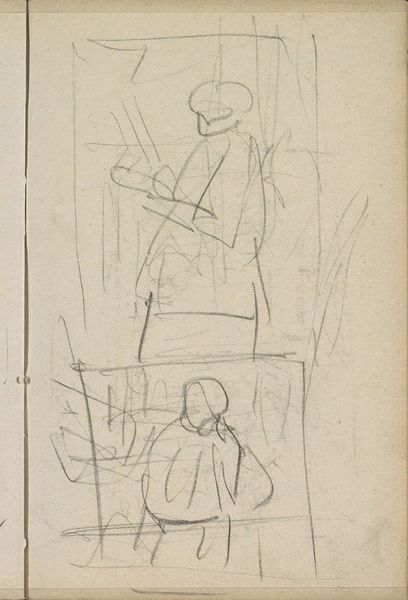

Editor: This is “Christina Rossetti’s Maude Clare – Figure and Head Studies” by John Everett Millais, dating back to 1859. It’s a pencil drawing on paper, a flurry of lines really. I'm immediately struck by its unfinished quality; it feels like a glimpse into the artist’s process. What stands out to you? Curator: Well, beyond the delightful peek behind the curtain, it's the expressiveness Millais achieves with so little. Those quick, light strokes give us everything we need. There’s a sense of captured movement, of fleeting emotion, like a whispered secret overheard at a crowded ball. The Pre-Raphaelites were fascinated by capturing heightened emotional states, wouldn’t you agree? And the composition with all the variations and groupings offers quite an interesting story to unlock as a puzzle. What do you notice about the subjects' interactions? Editor: I guess it’s in those sketched facial features that the human side shines through. Their relationship appears confrontational, maybe? There is such subtle, beautiful anger rendered! It’s so immediate despite the time that has passed! Curator: Yes, the power lies in implication. Look at the negative space, the implied gazes. The subjects are certainly engaged in the act of witnessing a confrontation of sorts. It echoes Rossetti's poem, doesn't it? The artist almost doesn’t even need a complete figure to evoke the narrative. Think about what a highly finished painting would conceal from us, actually, obscuring as much as revealing through laborious process. Editor: It’s amazing how a sketch can sometimes tell you more than a fully realized painting. Seeing the process really strips the image down. Thanks, I now see how less can be so much more. Curator: Indeed. That’s what is the most powerful and most endearing about art – isn't it? – Its endless capacity for evocative reinvention, revision and self-revelation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.