painting, oil-paint

#

portrait

#

figurative

#

portrait

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

figuration

#

romanticism

#

academic-art

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

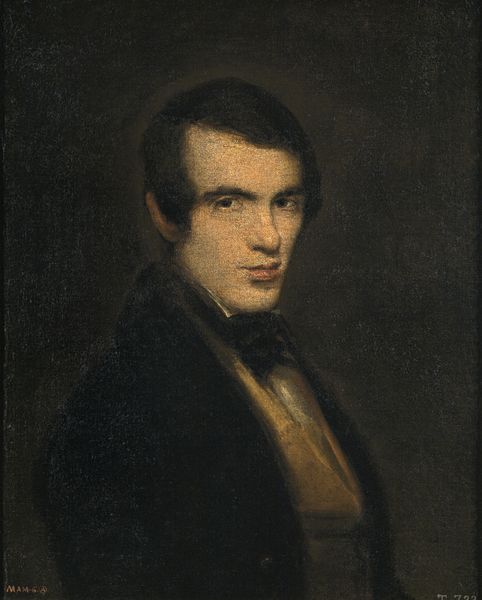

Curator: Let's delve into Jean-François Millet's "Portrait of a Man," circa 1845, rendered in oil paint. The subject presents an intriguing solemnity. What's your immediate impression? Editor: I’m struck by how tactile the painting is—almost like you could feel the texture of that wool coat and see the individual brushstrokes, each adding density to the surface. There’s a clear sense of the materiality and the labour that went into creating the figure’s very being. Curator: Indeed, observe how the tonal contrasts articulate form and define the sitter's contemplative gaze. The composition guides our eye directly to his face, illuminated against a more muted background. The formal qualities create a distinct sense of introspection. Editor: But that isn’t accidental, is it? Consider Millet's trajectory; wasn't he interested in depicting ordinary people and rural laborers? Even here, the portrait feels less about glorifying aristocracy and more about honestly depicting a working person, perhaps. I wonder about the man's profession. What materials did Millet have access to, and how did this influence his aesthetic choices and the level of accessibility? Curator: You raise a key point about accessibility. The restrained palette and lack of ostentation suggest a move away from purely decorative ideals. Yet, the masterful rendering demonstrates a clear understanding of academic conventions within portraiture. He deploys a visual vocabulary carefully crafted. Editor: Exactly, a vocabulary reflecting shifting social realities! Romanticism wasn't just about fanciful landscapes. It also prompted an investigation of authentic lives, the kinds usually hidden from artistic representation. The production— the mixing of pigments, the stretching of the canvas—these all played into constructing meaning in the final image. Curator: A harmonious blending of technical mastery with expressive intent. The balance between shadow and light invites the viewer to decipher not just who is represented but what they might be thinking. It has to do with composition but also the use of color. Editor: Ultimately, to appreciate a work such as this we must address its context. Examining artistic tools, available training, and evolving notions regarding labor are essential when analyzing art rooted within specific sociopolitical situations, like those of the 19th century. Curator: Agreed. By engaging with both form and sociohistorical context, a fuller understanding is made possible. Editor: And a richer experience had by any listener.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.