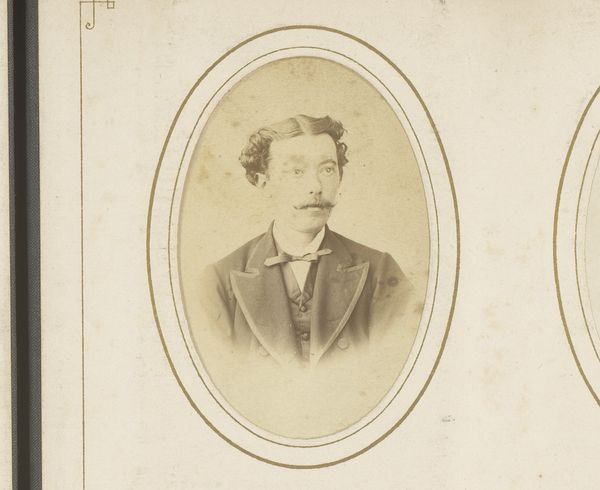

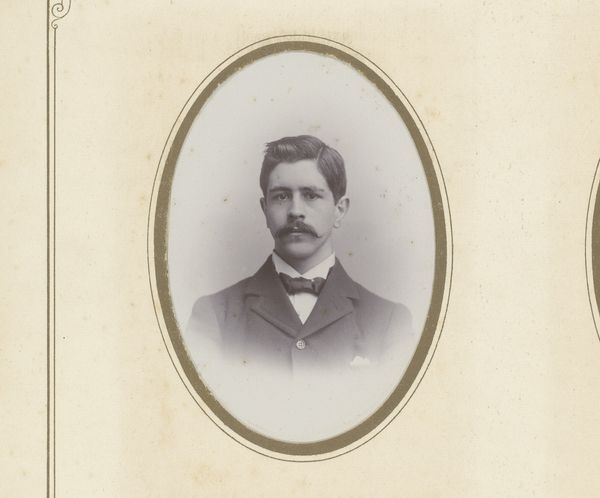

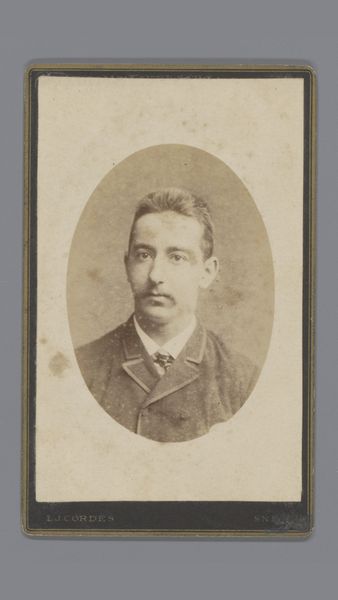

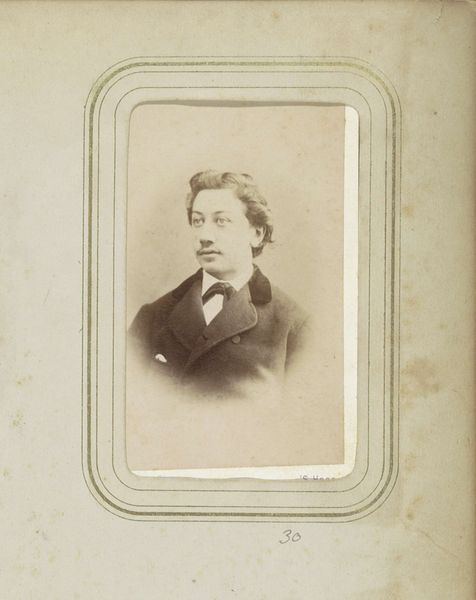

daguerreotype, photography

#

portrait

#

16_19th-century

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

19th century

Dimensions: height 85 mm, width 55 mm, height 105 mm, width 63 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

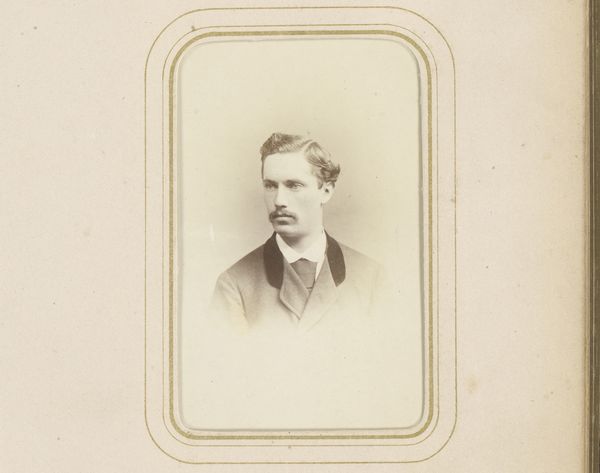

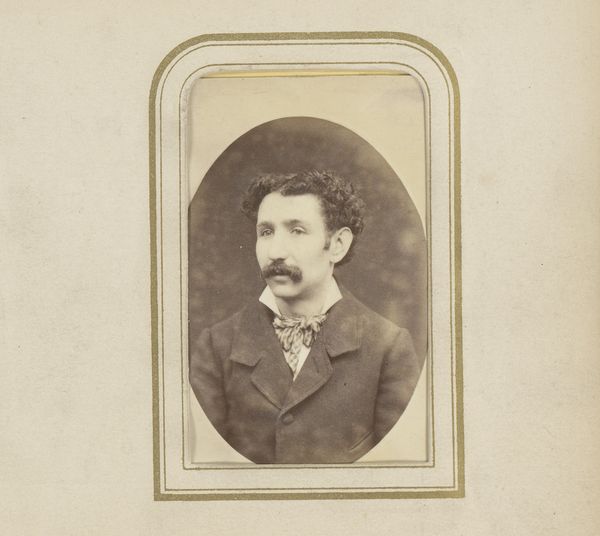

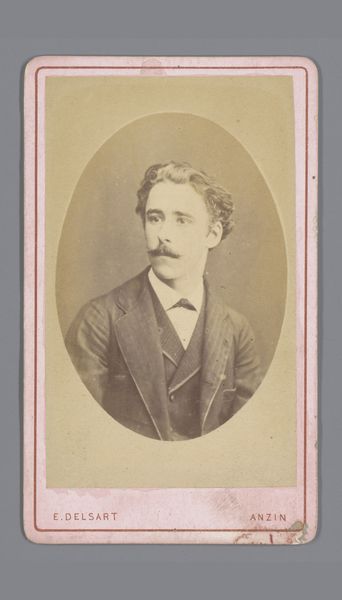

Curator: Look at this intriguing portrait. It’s listed as "Portret van een man met een stropdas" which translates to Portrait of a Man with a Tie. It was created sometime between 1870 and 1903, the photography attributed to De Lavieter & Co. Editor: The sepia tones immediately evoke a sense of solemnity. There's a certain rigid formality to the subject, emphasized by the tightly knotted tie, and the tight oval framing of the subject. The expression isn’t quite severe, though; it reads to me as more contemplative, or perhaps self-conscious. Curator: Self-consciousness is a fascinating read, particularly when thinking of daguerreotypes and the dawn of commercial photography. The photographic image promised both realism and posterity, though required long sittings, making for staged, rather serious visages. Consider, here, how the trappings of professional attire signify status, presenting an upwardly mobile respectability that served a rapidly changing society. The tie itself signals societal inclusion through an enacted participation of fashionable standards. Editor: Yes, absolutely. The portrait acts almost as a social marker, conforming to dominant class expectations even amidst the anxieties and hopes of a transforming social order. Looking closer, you also get a sense of fragility; the light etches a vulnerability onto the face that the suit cannot entirely mask. He isn't necessarily at ease in his clothing. What's striking too is the framing with those simple lines—they really constrain him, don't they? Curator: Restrictive boundaries can be sources of protection. These kinds of oval portrait frames echo similar framings in paintings and lithographs, placing the subject within an accepted context of status. In many ways, his expression evokes something quite persistent, an attempt to transcend temporal circumstances—his image carrying emotional resonance through repetition. The simple suit and tie become, not oppressive signifiers, but familiar forms. Editor: It’s true—these conventions of display gave accessibility. Although such rigid formal portraiture became less fashionable throughout the 20th century, there are definitely persistent performative displays still enacted through various modern social media engagements with similar, standardized, almost “boilerplate” expectations. Even now, images, what we present through digital or even written impressions, operate through codified performance. So yes, his image remains, his narrative continuing to resonate with new interpretations. Curator: I'm left with the intriguing juxtaposition of something temporal locked within an endless symbolic loop. Editor: It’s a portrait that continues speaking, offering us glances backward and considerations towards current conversations.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.