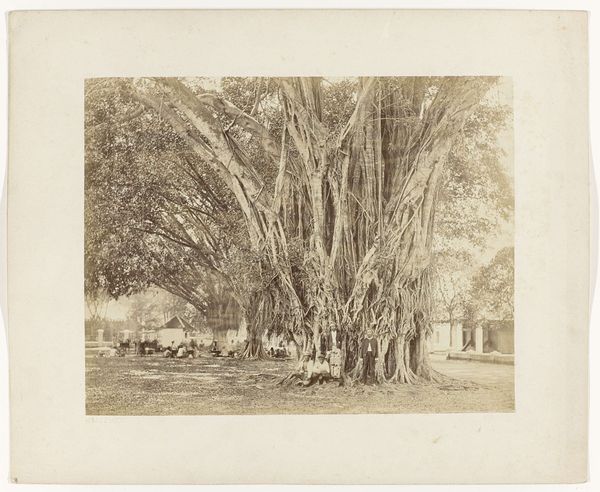

stereo, contact-print, photography

#

stereo

#

landscape

#

contact-print

#

photography

#

coloured pencil

#

realism

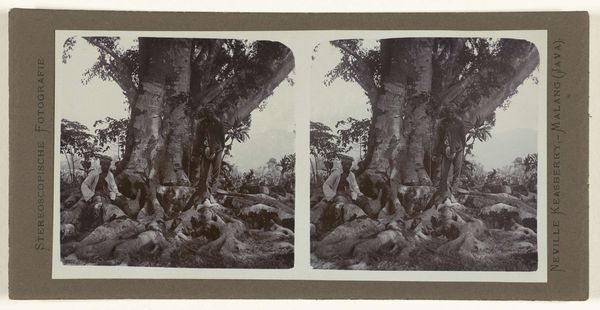

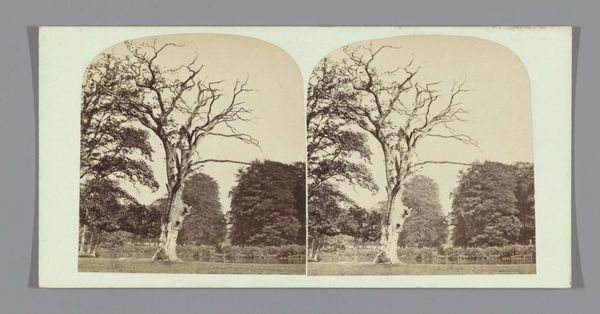

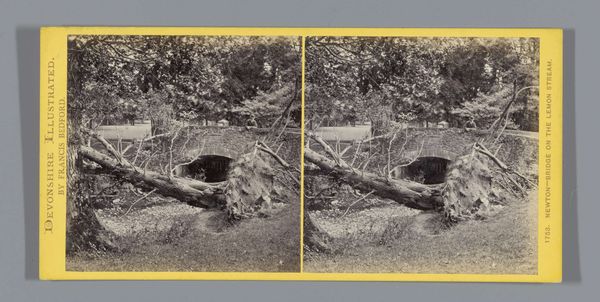

Dimensions: height 88 mm, width 178 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: What we have here is a stereoscopic photograph titled "Rubberboom in Florida," likely taken between 1891 and 1909. The photographer is anonymous, unfortunately. What strikes you initially? Editor: An uncanny, almost surreal sense of entrapment, despite it being a landscape. The branches loop and descend like constricting pythons, and the sepia tones add a layer of faded memory, a kind of decaying colonial dream. Curator: Intriguing. Notice how the composition itself emphasizes this looping effect. The stereo format gives an enhanced depth of field, drawing us into the tangled embrace of the tree’s boughs. It becomes a physical experience. The tonality ranges are limited, pushing similar grayscale intensities toward the back of the picture to give the branches much more depth, though the single person appears in the mid-plane. Editor: Yes, that depth! It’s almost claustrophobic, and the lone figure beneath the tree reinforces the symbolism of man dwarfed by nature. The tree becomes a powerful metaphor for the overwhelming forces of the natural world, or perhaps even the suffocating grip of colonialism itself, considering the region and time. "Rubberboom" suggests a human exploitation of nature's resources. The photographic medium is quite interesting since a contact print means we are very close to the thing recorded in the image; we have touched what we see. Curator: Precisely! We can also consider the tree as a subject with unique aesthetic properties. The repetition of curved lines, the textures of the bark and foliage. They compose a complex interplay of light and shadow that invites close visual analysis. Even the formal symmetry of the stereo format contributes. This offers us slightly offset images of the exact object to examine. I suspect there is a commentary in what can be known and what escapes simple optical inspection. Editor: A fruitful paradox! I also can't help but consider how rubber has shifted as a symbolic carrier across time. Now seen as tires and bouncy balls, in the nineteenth century, its novelty must have conjured thoughts about foreign wealth and power structures. Curator: Agreed, perhaps my formal perspective is somewhat dry after all. These cultural and historical readings certainly unlock a richer dialogue with the piece. It allows us to interpret how this strange natural figure relates to its place in the visual arts more broadly. Editor: It’s always such a dance between the inherent aesthetics and what meanings they gather to themselves, isn't it? Together, these insights help give an image of not only the artwork, but the worlds the artwork participates in and creates.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.