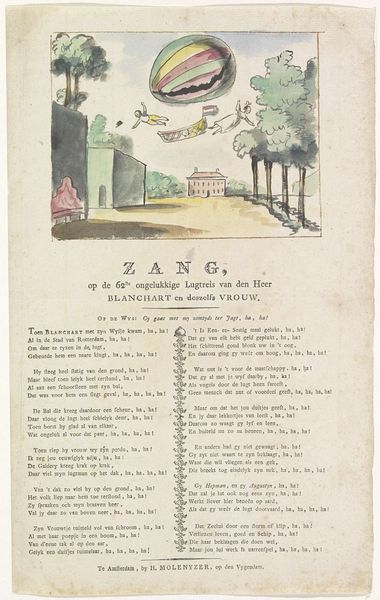

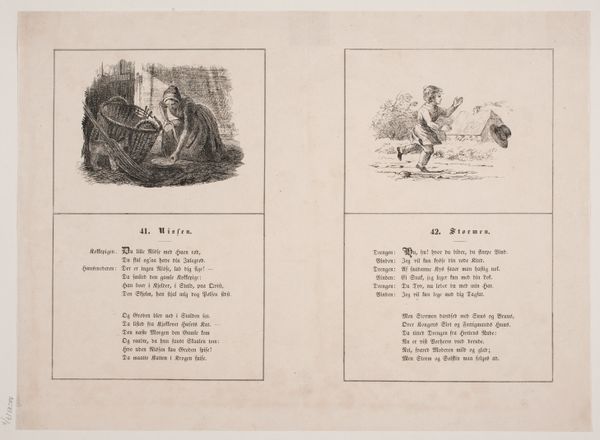

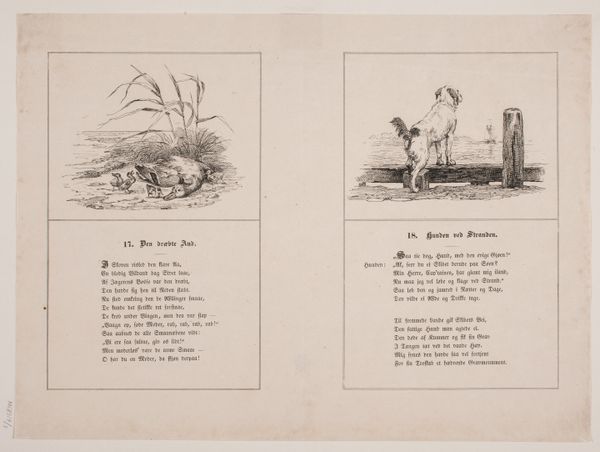

print, engraving

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

caricature

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

line

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 367 mm, width 234 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

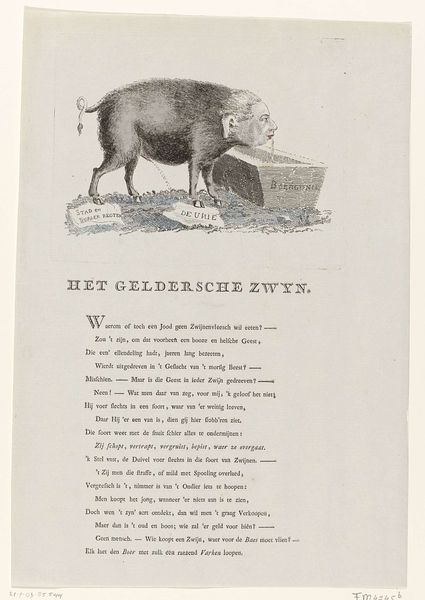

Curator: Looking at this print, created in 1787, what springs to mind for you? It's titled "Spotprent op Willem V en zijn vrouw en kinderen, 1787," at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Immediate impression? Chaotic and charged. There's a rawness in the line work and a blatant critique of power. The animals... are those pigs dressed in human faces? It's unsettling, and fascinating. Curator: Exactly. Consider the technique. This is an engraving, a medium reliant on precise labor and replicability. Its form and content implicate social hierarchies by mocking Willem V. Note the visual construction: pigs in human masks trampling on documents. What do you make of that? Editor: For me, those documents are key. They're the very foundations of Dutch society: laws, property rights. This print isn't just criticizing Willem V, it’s pointing to a systemic failure – a complete upending of the social contract, and who bears the cost when those at the top create policy divorced from those they affect. Curator: Indeed. The print, as a material object, exists to circulate these sentiments widely. The means of production – the labor of engraving, the printing process itself – are fundamental to its purpose: dissent as a collective activity. This challenges a simple "high art" categorization, locating meaning in its usage and propagation. Editor: Right. We should contextualize this work, also, in light of the broader issues that inform the caricature. Who is profiting, whose land is seized and enclosed? This work speaks directly to those inequities. Curator: Considering the accessibility of printmaking at that time, its capacity to disseminate this image would likely impact public discourse and galvanize resistance against perceived oppression and, indeed, to promote the virtues of revolution. Editor: It shows us how effective visual culture is for encouraging dialogue. This seemingly simple image is pregnant with societal anxieties and acts as a critical text against corruption and dispossession of wealth by those in charge. Curator: Yes, this engraving allows us to rethink established historical narratives around agency, dissent, and who the real authors of change were, as well as the many ways visual messaging becomes a symbol and catalyst of change. Editor: Agreed, reflecting on this artwork now makes me aware of the continuing role and responsibility artists have to examine and challenge oppressive powers, reminding us that art can operate in the service of revolutionary thought.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.