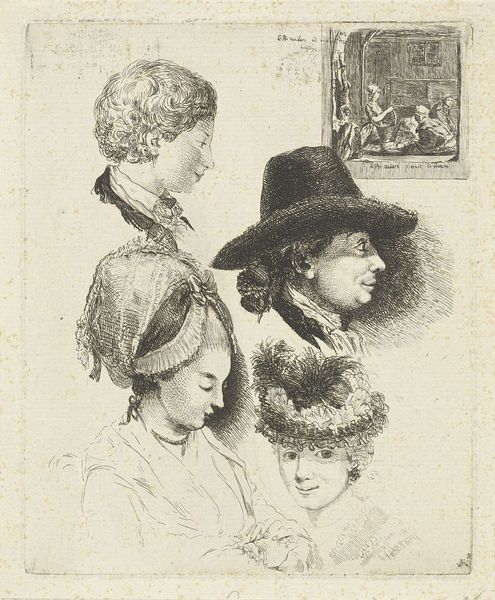

drawing, pen

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

#

pencil sketch

#

pencil drawing

#

pen

#

pencil work

#

academic-art

Dimensions: height 159 mm, width 128 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

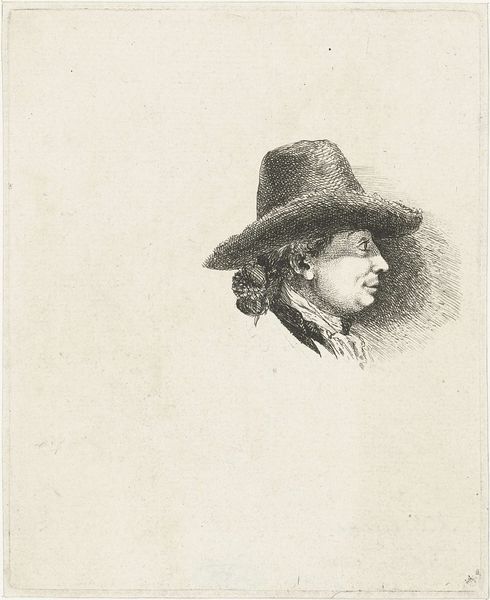

Curator: Here we have Louis Bernard Coclers’s "Studieblad met portretten van Louis Bernard Coclers en zijn familie," a drawing created around 1780 using pen and pencil. Editor: My initial reaction is that it feels very intimate and reserved. There’s a quietness to it, despite it being a family portrait, of sorts. A stark study in observation. Curator: Precisely. Note the restrained lines and the classical profiles, indicative of Neoclassical sensibilities. Observe how Coclers employs hatching to create subtle tonal variations, particularly in rendering the faces and clothing. Editor: Yet, one wonders about the absence of interaction. The figures seem disconnected, each trapped in their own internal world. Perhaps it reflects the limitations placed on women during that period. Their gaze is downcast or averted, a visual representation of restricted agency. Curator: Interesting observation, but focusing on the composition, the arrangement of the heads creates a visual rhythm, directing the viewer's eye across the picture plane. The varied textures, from the woman’s intricately detailed cap to the man’s rough straw hat, add depth and visual interest. Semiotically, these elements speak volumes. Editor: I agree with your observation about rhythm, and I’d suggest further considering how those textured and constructed realities mirror their roles in society. The straw hat signals a life of work, of outdoors; and the bonnet signals an engagement in the decorative domestic sphere. The act of rendering those realities becomes the real significance of the drawing, not the technical prowess. Curator: Perhaps we're applying contemporary sensitivities to an eighteenth-century work, reading into the artist's intentions what may not have been there. Coclers may have simply been striving for an objective portrayal, capturing likenesses in the manner of his time. Editor: But can we ever truly divorce ourselves from the socio-historical context? Even the pursuit of “objectivity” is laden with cultural baggage, reflecting the dominant ideologies of the time. And furthermore, why would we want to? By viewing the artwork through lenses of gender, race, and power, we enrich our comprehension. Curator: A perspective to consider indeed. I find it personally to be more a case study in line and light, but a valuable conversation nonetheless. Editor: Agreed. May viewers find meaning through whichever avenue resonates!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.