print, photography

#

pictorialism

# print

#

landscape

#

nature

#

photography

#

england

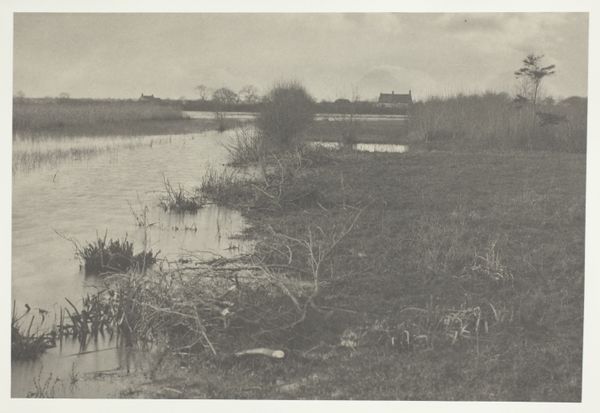

Dimensions: 17.6 × 28.9 cm (image/paper); 28.6 × 40.7 cm (album page)

Copyright: Public Domain

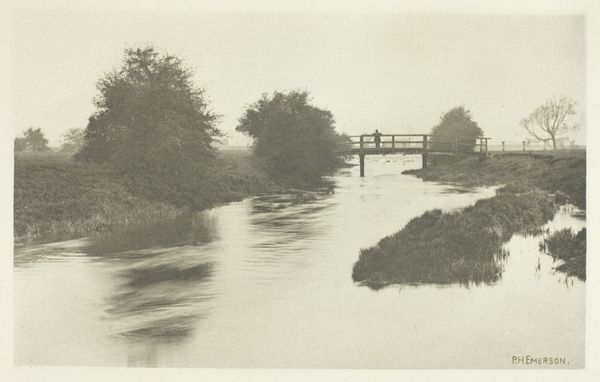

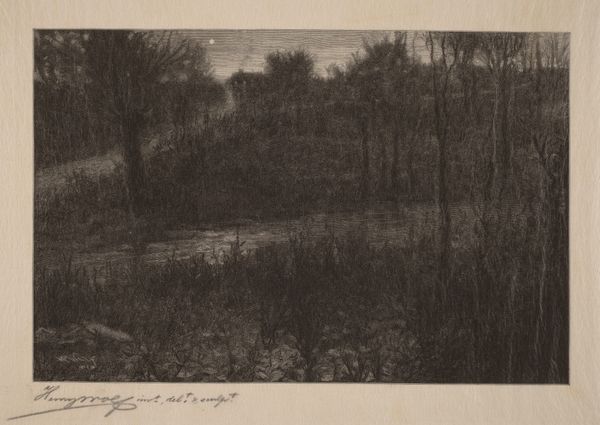

Curator: Here we have Peter Henry Emerson's "The Fringe of the Marsh," a photograph from 1886, currently residing here at The Art Institute of Chicago. Editor: It’s remarkably subdued, isn't it? The gray tones are so muted; it’s almost melancholic, especially the still water and the indistinct forms of the buildings in the background. Curator: Indeed. Emerson, a key figure in Pictorialism, sought to elevate photography to the level of art. His techniques, like soft focus, mirror the aesthetic concerns prevalent in painting at the time. This image speaks to his dedication of showcasing the dignity of rural life in England, as seen in this fenland landscape. Editor: I am struck by the formal composition. The texture is key here: how the reeds and grasses define a subtle layering in the visual plane leading the eye to those dwellings along the horizon. It makes one aware of the image's materiality and what his artistic choices invoke. Curator: Absolutely. Pictorialism in general, and Emerson particularly, rejected the notion of photography as purely documentary. There was considerable debate among photography circles. His techniques—manipulating the printing process, using specific paper—emphasized the photographer’s artistic hand, their role in creating a specific narrative, often highlighting local labor. Editor: He masterfully manipulated light and shadow; one could easily view its surface as impressionistic. We must acknowledge this visual language. Emerson utilized the science of optics, translating them to convey mood through careful attention to composition and gradations. Curator: And by representing the natural world in a specific context: agriculture, labor relations, and the impact of industrial progress on those communities. The value shifts when considering how many rural areas were impacted through increased mechanization and enclosure, and whether the reality truly lined up with Emerson’s idealized view of English countryside life. Editor: A stark reminder to decode imagery by acknowledging not only content but form! His emphasis on structure and aesthetics enables our eye to experience his work, providing an entry into an exploration into its deeper meaning. Curator: Precisely! Through the lens of process, and considering how this art piece contributes towards shifting attitudes surrounding class and the romanticization of certain kinds of manual labor, there’s an opening for considering class relationships as commodities to be displayed or bought. Editor: Understanding its semiotic complexity enables us to recognize the art not as mere depictions but constructions. Hopefully visitors now feel they possess some of the tools and frameworks to think about artwork from varying and insightful viewpoints.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.