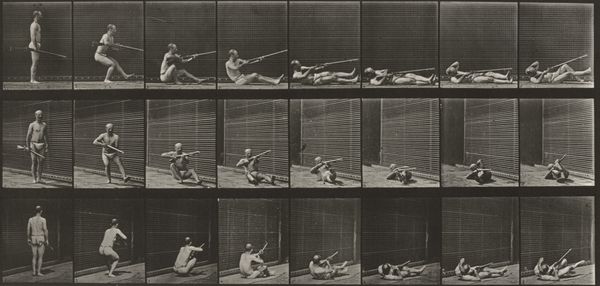

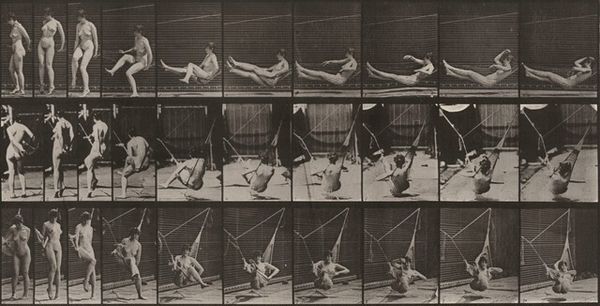

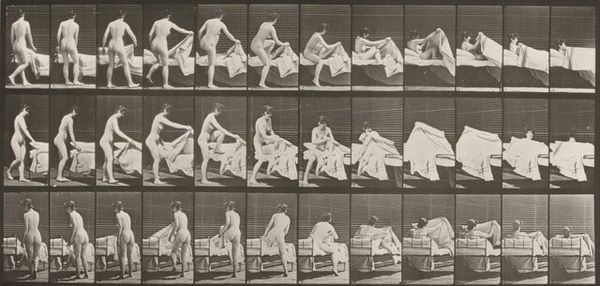

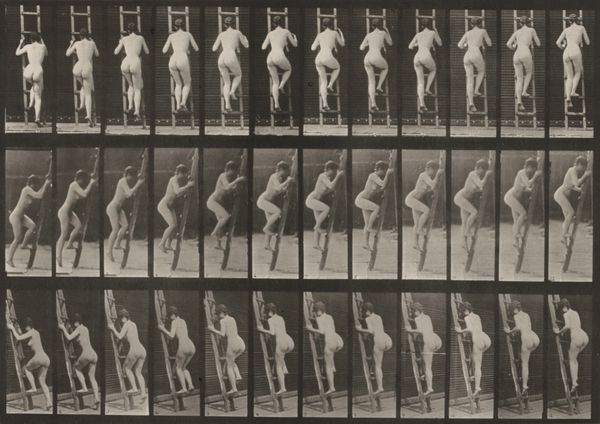

Plate Number 267. Turning and changing position while on the ground 1887

0:00

0:00

#

simple decoration style

#

natural stone pattern

#

muted colour palette

# print

#

sculpture

#

nude colour palette

#

historical fashion

#

stoneware

#

veil as a decoration

#

wedding dress

#

bridal fashion

Dimensions: image: 15.7 × 45.3 cm (6 3/16 × 17 13/16 in.) sheet: 47.8 × 60.2 cm (18 13/16 × 23 11/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

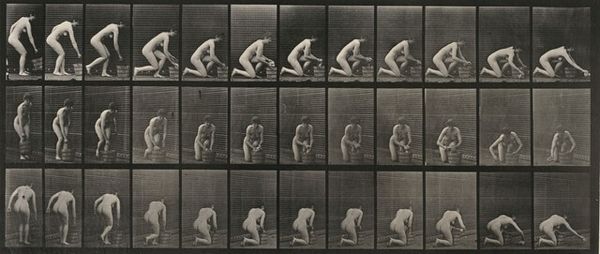

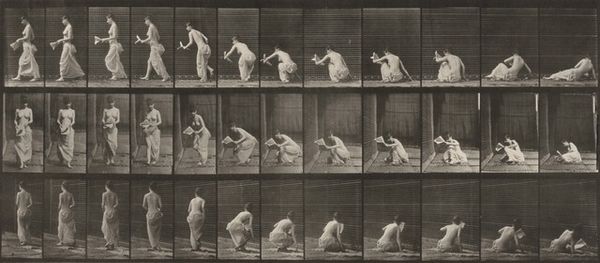

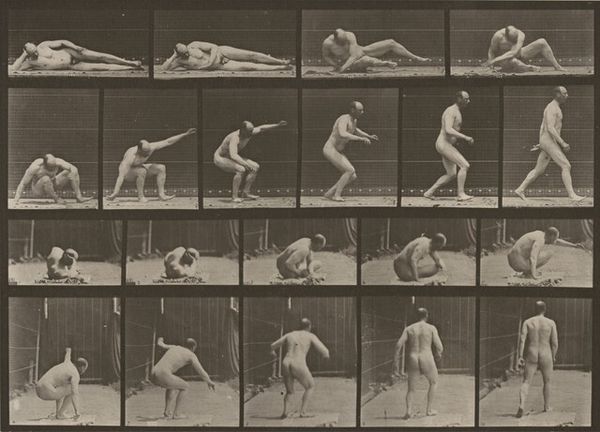

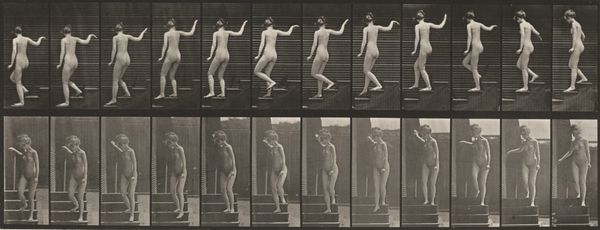

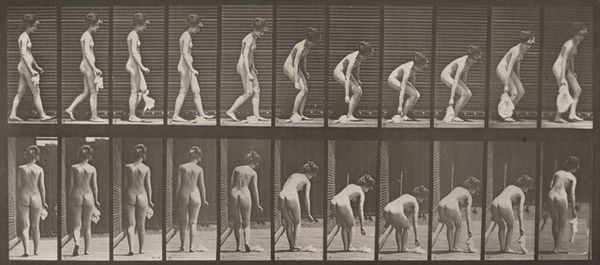

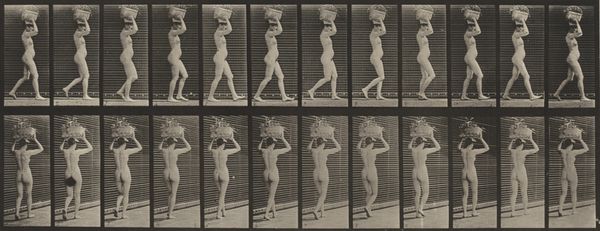

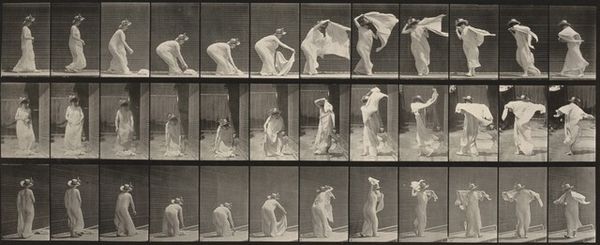

Curator: Eadweard Muybridge's "Plate Number 267. Turning and changing position while on the ground," dating back to 1887, is a fascinating study of motion. Its monochrome aesthetic is immediately striking, wouldn't you agree? Editor: Yes, the stark, grid-like presentation of the sequential images feels quite clinical, almost like a scientific document rather than what we traditionally consider art. There’s a vulnerable stillness amid all that movement, though, isn't there? Curator: Indeed. Muybridge was interested in dissecting movement, driven by technological advancement and scientific inquiry. Think about the context: it reflects a late 19th-century fascination with documenting and analyzing the human body. How were women seen during that period? How did they function in scientific discourse? Editor: Absolutely. It prompts questions about how women’s bodies were and still are being perceived as spectacles, under scientific examination. The sequencing makes you hyperaware of the physical vulnerability, and perhaps objectification, inherent in capturing such intimate actions frame by frame. Was the model's consent thoroughly informed, especially by today's standards of ethical representation? Curator: Those are precisely the important, challenging questions we should consider. Muybridge’s work existed within, and perpetuated, specific power dynamics. While he made advances in photographic technology, his depictions were deeply embedded in his cultural moment. Museums must show, but also investigate and interrogate how these images are framed, and the politics embedded within that imagery. Editor: Exactly. The dialogue between art history and current ethics is what helps to really challenge these narratives. Examining this series allows us to explore important discussions about the complex politics of gender, representation, and observation. It becomes an active piece engaging in contemporary issues and dialogues. Curator: It shifts the focus of discussion from 'what we see' to 'how and why we see,' and that, perhaps, is one of art history's most critical roles. Editor: Precisely. To reflect and, hopefully, instigate critical engagement with art’s power to shape societal perspectives.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.