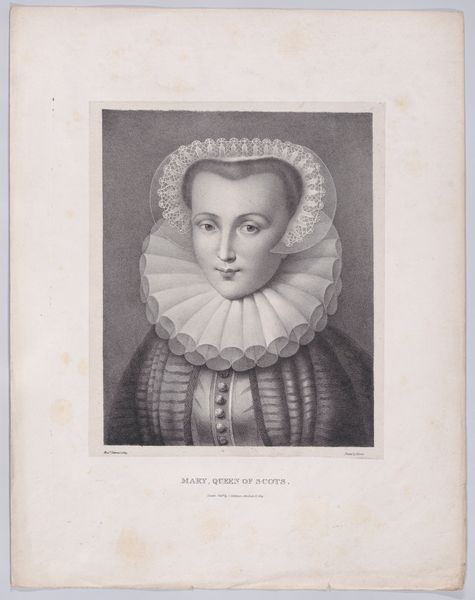

Dimensions: Sheet: 6 7/8 × 12 11/16 in. (17.4 × 32.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: Here we have a print titled "Mary, Queen of Scots" made sometime between 1850 and 1871, attributed to Schenck & McFarlane. It's a very detailed portrait, and I immediately get a sense of formality, even sadness, from her expression. What do you see in this piece, considering the weight of imagery? Curator: This image presents us with more than just a portrait; it offers a glimpse into cultural memory. Notice the meticulous detail in her lace collar and headdress. Lace in portraits from this period was a symbol of status and femininity but it can also be perceived as restrictive, a gilded cage, can’t it? What sort of ideas does it evoke for you? Editor: That's a compelling interpretation. The lace is beautiful, but yes, it also seems constricting, almost like a barrier. So, are you saying these details were deliberately chosen to convey certain meanings about her life and role? Curator: Precisely. Symbols are rarely accidental. Consider Mary's story—a queen, a prisoner, and ultimately, a martyr. Artists throughout history have used her image to explore themes of power, betrayal, and tragedy. It served to consolidate her image as Catholic martyr after her death. How do you see that playing out here? Editor: Now I see the sadness more clearly; the lace almost emphasizes it, setting the stage for her fate. It is quite striking how a garment may inform perception, especially after hearing you describe the context of the symbol. Curator: It also highlights how artists embed these cultural memories. The image of Mary has gained more weight with history. A sad, but poignant life. Editor: Definitely! Thinking about how historical context informs art in the romantic period truly changed my perception. Curator: And the reverse too; images inform the context we come to know!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.