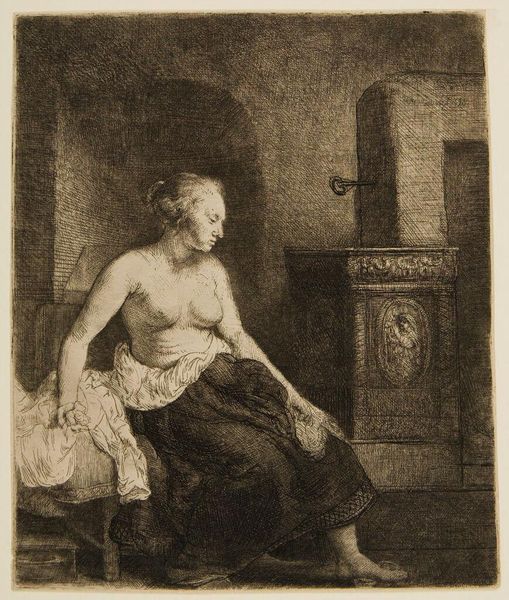

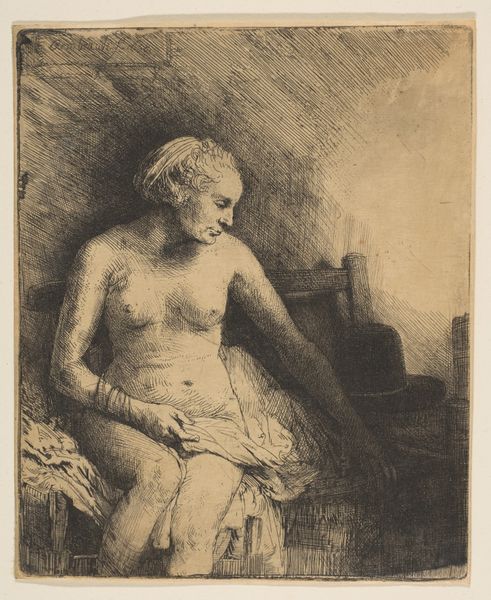

drawing, print, etching

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

etching

#

portrait reference

#

nude

#

realism

Dimensions: Plate: 8 15/16 × 7 5/16 in. (22.7 × 18.6 cm) Sheet: 9 3/16 × 7 5/8 in. (23.4 × 19.3 cm) Frame: 21 × 16 in. (53.3 × 40.6 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This etching by Rembrandt van Rijn, made around 1658, is titled "Woman Sitting Half-Dressed beside a Stove." It resides here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: There's a subdued intensity to the composition. The stark contrast and rough hatching give it a very somber, almost anxious feel. Curator: Yes, look closely at how Rembrandt masterfully uses shadow and light. Notice the geometric rendering of the background elements: a hearth, a chair, all receding from a light that graces the sitter's profile. There is almost a study in how light both reveals and conceals form. Editor: The image troubles me. Given its date, it's almost certain this depiction is from a male gaze. A woman presented, partially clothed and caught within the domestic space. One can't ignore the power dynamics at play here. It could be a social commentary on the everyday vulnerability experienced by women of that era, exposed to exploitation by those in power, though it lacks explicit context, there’s just the hint of everyday vulnerability. Curator: Undoubtedly, an interpretive layer. Yet I find the formal language quite fascinating in its own right: it is the dynamism of the line and stark interplay of dark and light values which creates a visually compelling form—quite aside from whatever message you attribute. Editor: But form does not exist in a vacuum, does it? It always arises within, and refers back to, social contexts. We cannot just unsee our understanding that the history of art is unfortunately entangled with representations like these, often made from inequitable power dynamics. Even in admiring Rembrandt’s use of light, we must acknowledge the historical circumstances from which it emerges, which may or may not critique, but at least references those same conditions. Curator: I agree that context is crucial, yet I find the stark light more as something transcending these earthly interpretations; it points towards an elegance beyond a straightforward patriarchal lens. We shall not, and perhaps cannot, reach full interpretive resolution, alas. Editor: And isn't it within those tensions, within those unresolvable ambiguities, that the etching gains meaning? Curator: Indeed, perhaps that’s where its enduring resonance is discovered. Thank you. Editor: A pleasure.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.