drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

death

#

human-figures

#

figuration

#

human

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

angel

Dimensions: sheet: 6 x 6 7/8 in. (15.3 x 17.4 cm) plate: 5 15/16 x 6 3/4 in. (15.1 x 17.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

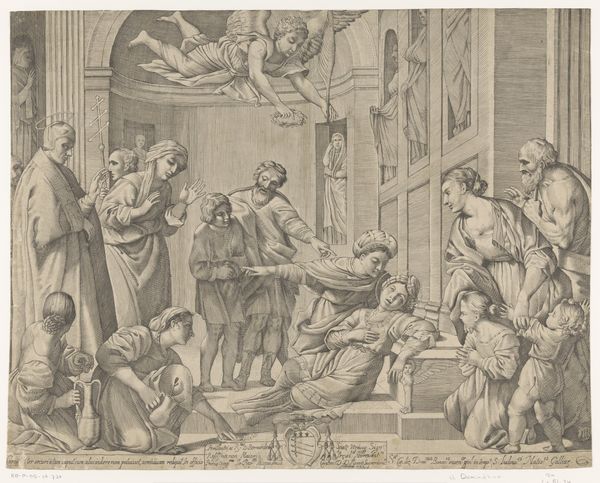

Curator: Here we have Johann Friedrich Greuter's "The Death of St. Cecilia," an engraving dating from roughly 1640 to 1660. It’s currently held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. My first impression is of overwhelming density. So many figures crowded into the space, and the sharp lines of the engraving… It creates a sort of agitated drama. Editor: Absolutely. The compressed composition seems appropriate, considering the subject matter. St. Cecilia, patron saint of music, is depicted here at the moment of her martyrdom. If we delve into the visual vocabulary, it is an iconic rendering. Curator: Can you elaborate on that? What makes it so iconographically significant? Editor: Well, look at the angel descending with the laurel wreath, a traditional symbol of victory and heavenly reward. Note, too, Cecilia herself is not depicted as passively suffering. The light around her and the upward, expectant gaze suggest a transcendence beyond the immediate physical ordeal. She clutches her heart; music of a different register! Curator: The gestures of the surrounding figures are also telling, wouldn’t you agree? Some recoil in horror, while others seem to offer comfort or aid. What do you think the woman kneeling at her feet with a pitcher is signifying? Editor: Most probably preparing the Saint's body for final rites or symbolically cleaning Cecilia. You can see here echoes of classical visual arrangements being translated into the heightened emotionality of the Baroque. What's fascinating is how the drama functions, really. The gestures of care mingle with repulsion... which really encapsulates the social tension surrounding sanctity and martyrdom at the time. To publicly be 'of faith' was not always straightforward and was fraught with difficulty, depending on who and where you were. Curator: It is, undeniably, powerful. Looking closely, it speaks to an era grappling with faith, mortality, and the social theater surrounding both. The image doesn’t simply illustrate an event; it stages a whole network of beliefs and fears. Editor: Indeed. The image speaks to an array of conflicted emotions that frame the subject. And to reiterate, martyrdom narratives during the 17th century are always charged sites where personal conviction confronts public scrutiny. A reminder of the social and personal forces converging through imagery.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.