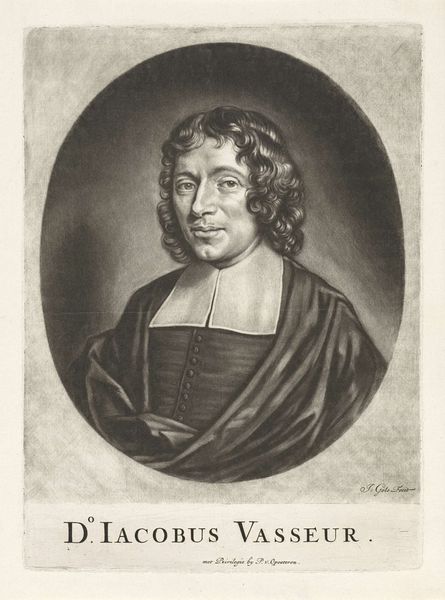

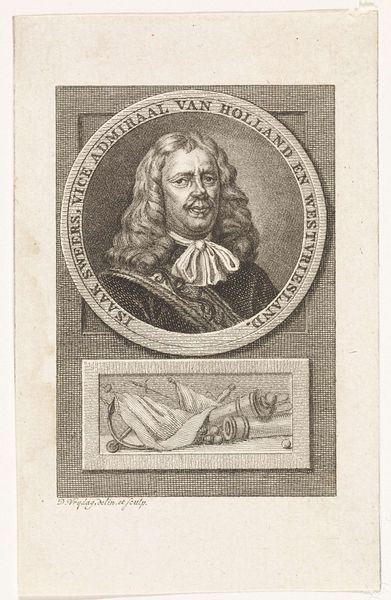

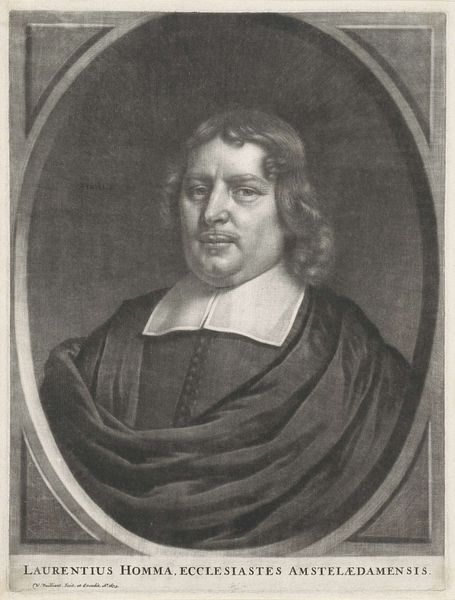

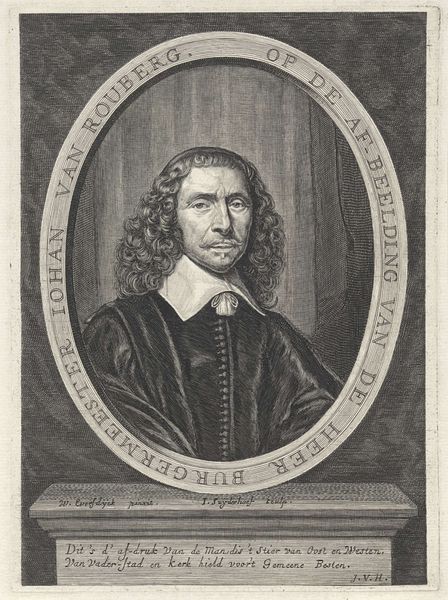

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

old engraving style

#

historical photography

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 290 mm, width 208 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

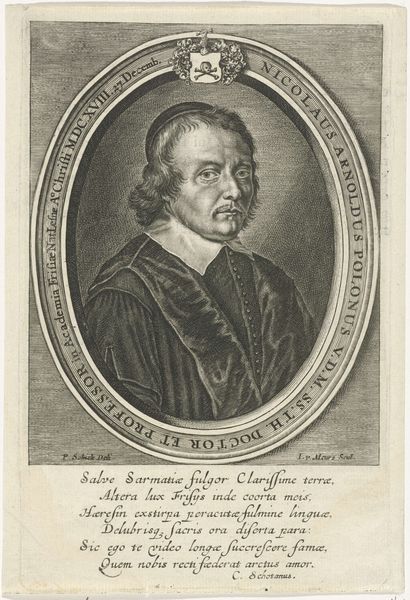

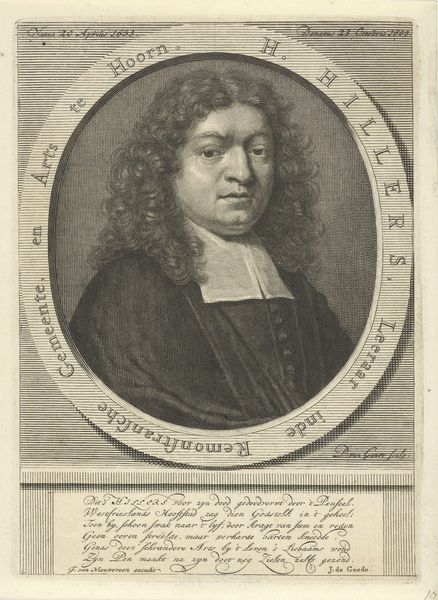

Curator: Look at this stunning engraving, "Portret van Nicolaas Haring," created by Jacob Gole in 1685. There's an almost tangible presence to the man. What's your initial impression? Editor: Austere. I feel a certain... distance? He looks directly out at us, yes, but with a closed-off demeanor. Is it the formal setting, that dark clothing against the lighter collar? Or is it something deeper? Curator: It's interesting you say austere. I see a kind of gentle intelligence, even vulnerability. The delicate lines around his eyes, the soft curls... Perhaps it's the humanist in me, always searching for the tender moments. And remember, portraiture of this era was often about projecting status. Editor: Exactly! That's precisely where my "distance" reading comes from. We can't separate this image from its context: 17th-century Dutch society. He's a pastor, important to the community, and that's the image he wants to convey. This isn't some candid shot; it's carefully constructed. Curator: Ah, but isn’t there a dance, always, between the intended image and what bleeds through? I find the engraving technique fascinating – those fine, deliberate lines building depth, hinting at the inner life he holds beneath. Editor: Yes, and Gole was a master engraver. Still, to your point about “bleeding through,” I'm struck by the gaze. There's something in the set of his eyes—wary maybe?—that seems to push against the pious pastor persona. What was he like outside his profession? We'll never really know, will we? Curator: Maybe not know *fully*, but isn’t that the magic of portraiture? This artwork—with the Latin phrases circling the oval frame like whispered secrets—gives us just enough to spin our own narratives. To imagine. Editor: That’s the seductive pull, indeed, even if our narratives must acknowledge the limitations and power dynamics inherent in this historical representation of identity. Ultimately, portraits offer a mirror reflecting back not only the sitter but also the viewer's own assumptions and biases. Curator: Beautifully said. So, we started with austerity and distance, and now we’re considering reflections and biases… I’d call that a journey worth taking.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.