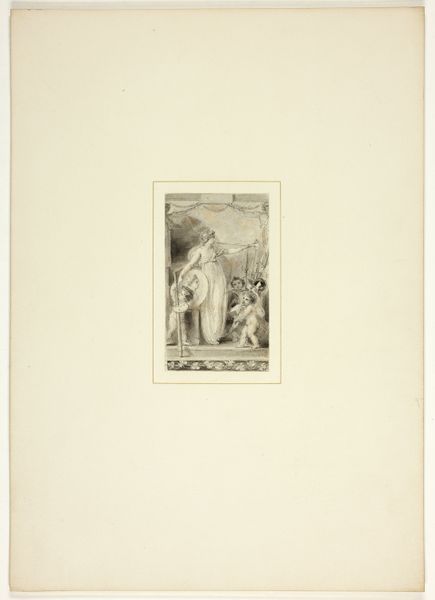

Dimensions: height 231 mm, width 169 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

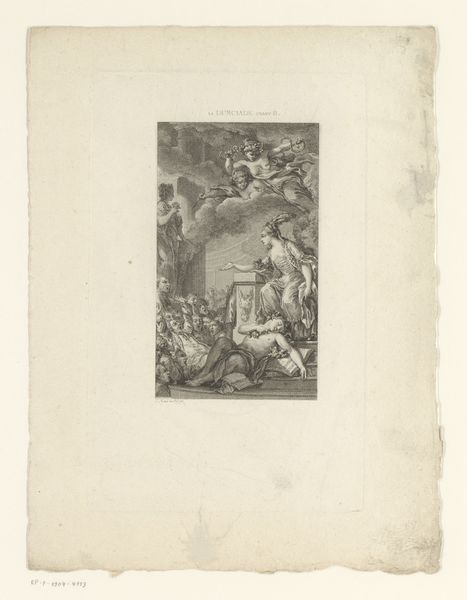

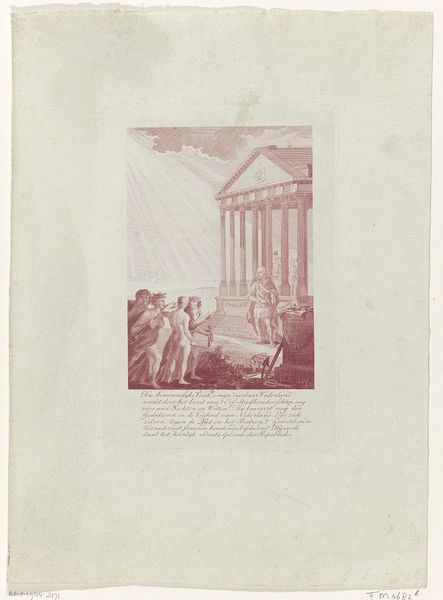

Editor: We’re looking at “Buste van dichter gelauwerd door drie muzen,” an engraving from 1783 now at the Rijksmuseum. There’s a classical feel with the muses and bust, but it seems almost overly celebratory, a bit staged, wouldn't you say? How do you interpret this work? Curator: I see this piece as a complex visual argument deeply embedded in the Enlightenment’s evolving understanding of genius and artistic patronage. The act of “laureling” itself—bestowing honor through a wreath—speaks to the power structures at play. Notice how the muses aren't simply bestowing gifts but crowning a *male* poet, reinforcing a gendered hierarchy of creative authority. Editor: So, it’s not just about honoring the poet, but about solidifying existing social norms? Curator: Exactly. Consider the role of the print itself: it was a medium accessible to a burgeoning middle class, disseminating ideas about artistic merit and who gets to define it. How does the artist leverage classical imagery to legitimize contemporary power dynamics, or perhaps critique them? Editor: I didn't think about it that way. The medium as a tool for social commentary, fascinating! Curator: It's also worth noting the political context of 1783. Revolution was brewing. Were artists using allegory to subtly question or reinforce the established order, given that direct critique could be dangerous? What does this overt display of praise, mediated by idealized figures, tell us about the artist’s role in shaping public opinion? Editor: It reframes the piece entirely. It's much more than just an image; it's a statement about art, power, and society. Thank you! Curator: Indeed, it reminds us that art rarely exists in a vacuum. It’s crucial to consider what art does in its historical moment, and the societal pressures it reflects.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.