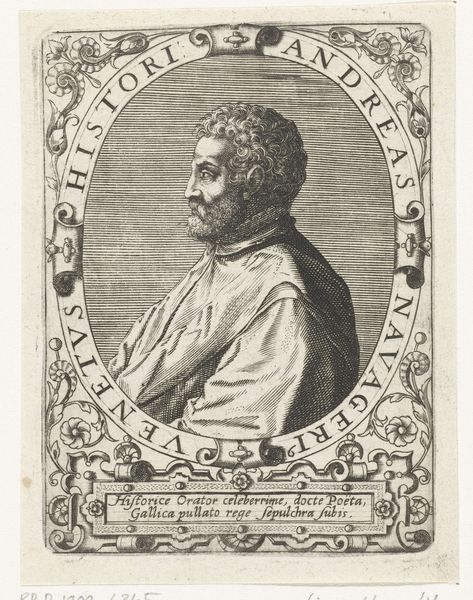

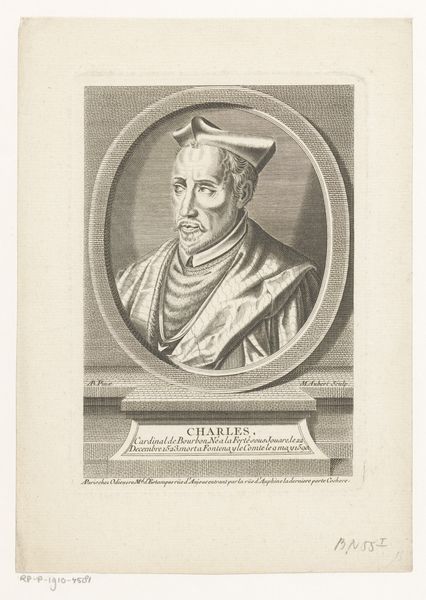

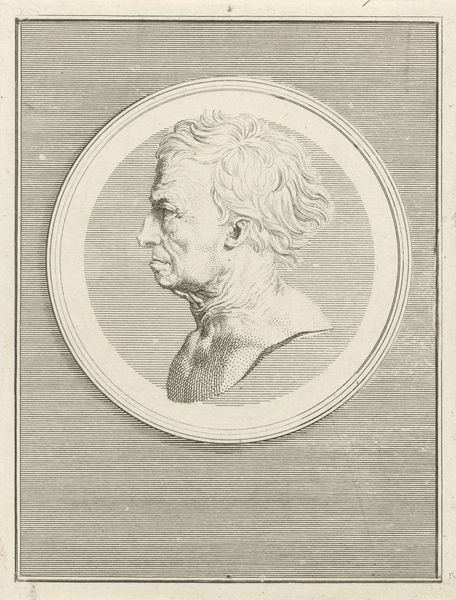

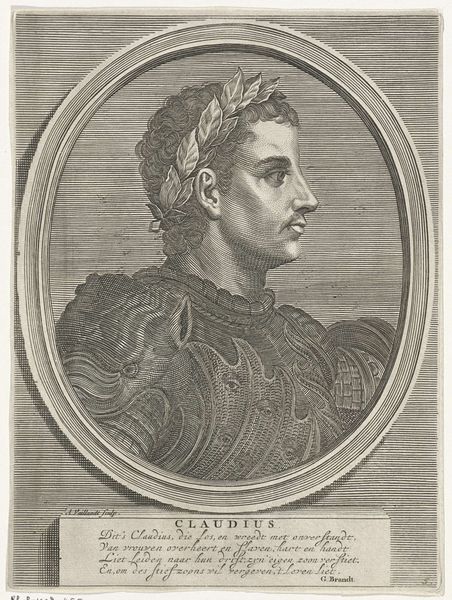

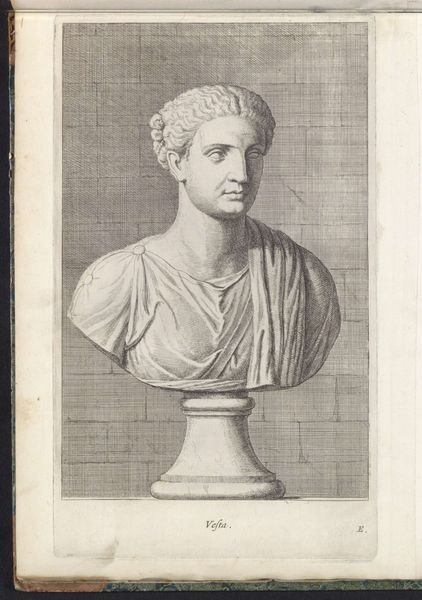

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

caricature

#

figuration

#

framed image

#

line

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 170 mm, width 132 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

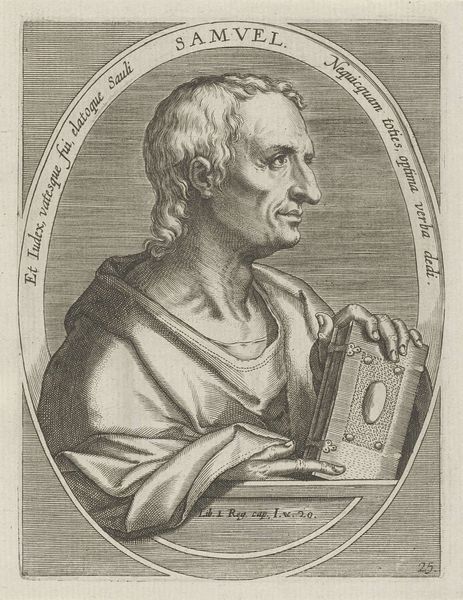

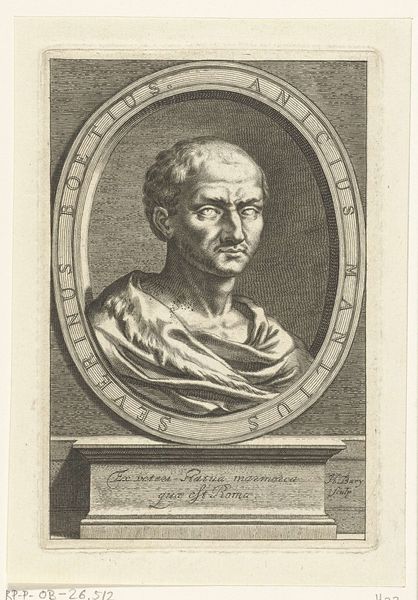

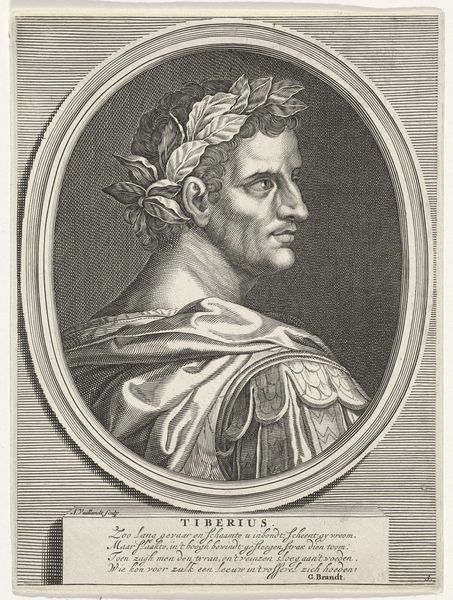

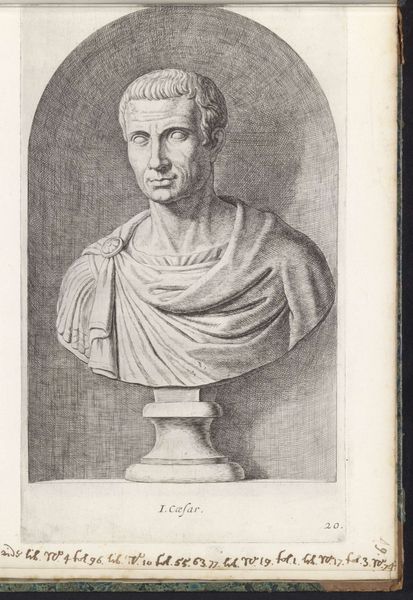

Curator: This print, simply titled "Gad," created in 1613 by Cornelis Galle I, shows a figure in profile, encased in an oval frame. It’s an engraving, part of the Rijksmuseum's collection. What strikes you first? Editor: He seems weathered. You can see the signs of hardship in his face. The artist captured something melancholic. He’s got his hands clasped, resting them. I wonder about his burdens. Curator: Well, Gad himself in the Bible was one of Jacob's sons. His name signifies "good fortune." The phrase surrounding him on the oval relates to a choice between war, plague, and famine; a bit ironic, perhaps. Editor: Irony definitely seems to be at play here. Look at his portrait; you read those furrows, that set of the jaw...and the choice is suffering in all forms? Even the clasped hands look tense. There’s almost a visual paradox. It speaks to the complicated relationship humans have always had with fortune. It’s rarely straightforward. Curator: The composition itself is classic Baroque: dramatic contrast and a flair for representing emotion, despite the simple lines. The line work emphasizes the depth and texture. What I also find telling is the use of scripture at the bottom, tying Gad directly into this historical context. Editor: Indeed. Context is essential here; consider the plague ravaging Europe during that period, then wars brewing, famine always looming...This wasn't just art, it was mirroring collective fears back to the viewers, but anchored in this biblical character. I keep noticing, too, how contained he seems within that oval. Like fate is this unescapable ring. Curator: I completely agree; he is certainly not free to move. This is not just Gad the figure. This is Gad as a symbolic emblem of a tumultuous world, condensed into lines and shadow. The detail for an engraving of that era really draws you in. Editor: Makes you reflect on today, doesn't it? Curator: It certainly does. A poignant statement on human condition—as resonant today as it was then.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.