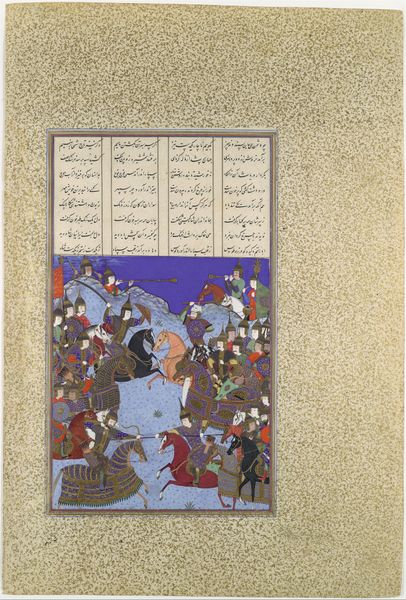

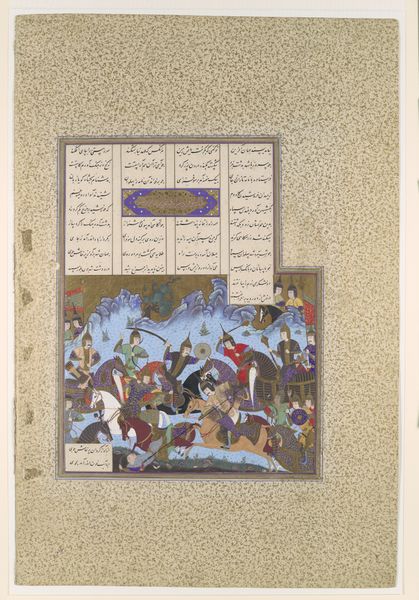

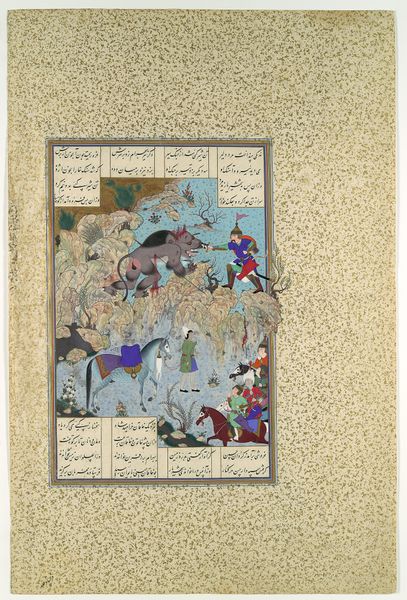

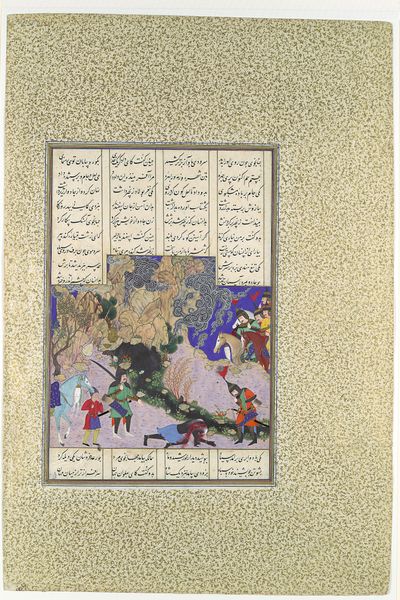

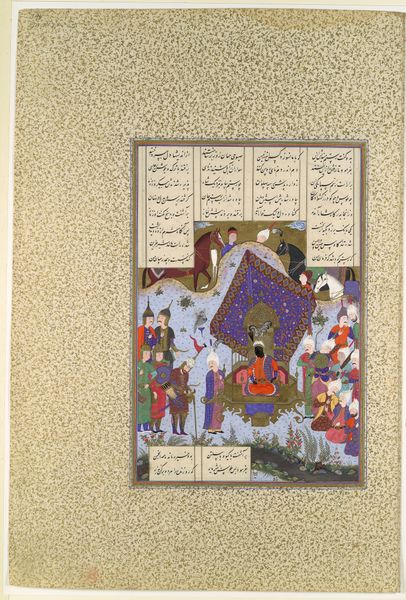

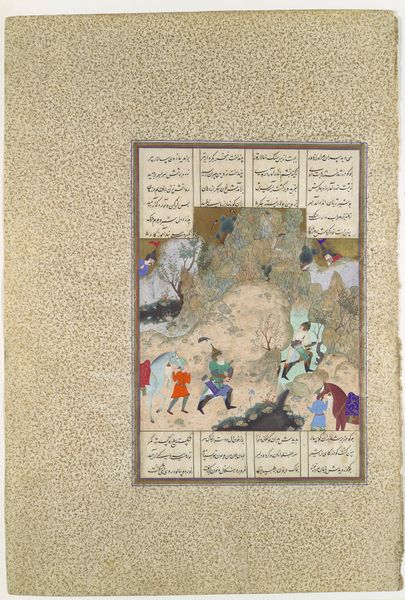

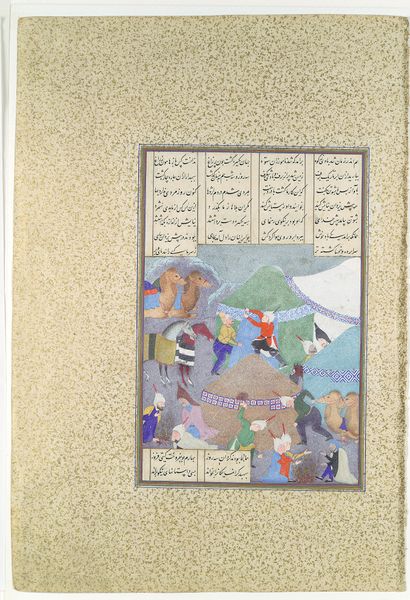

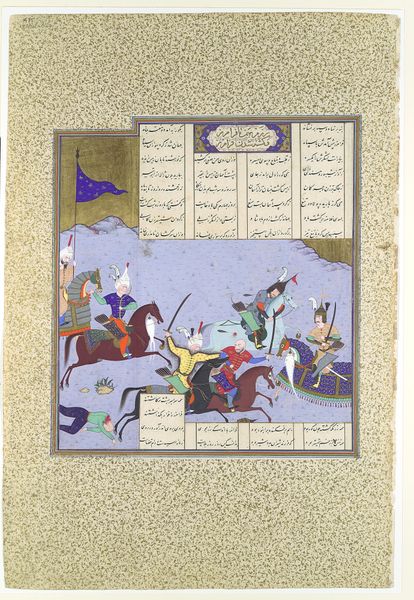

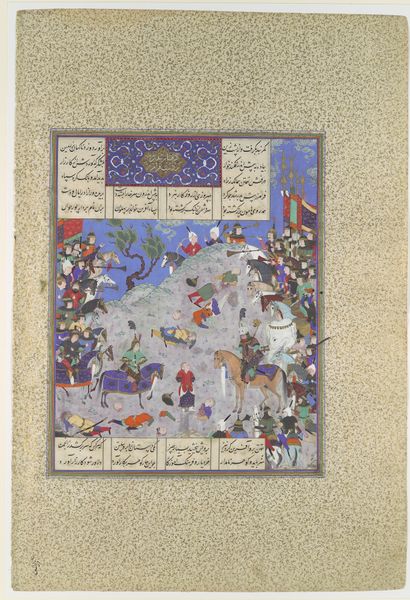

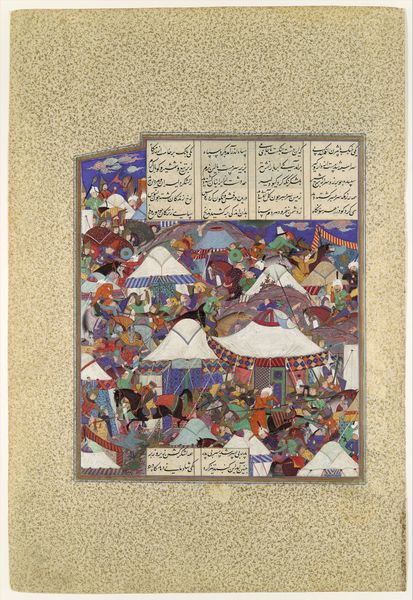

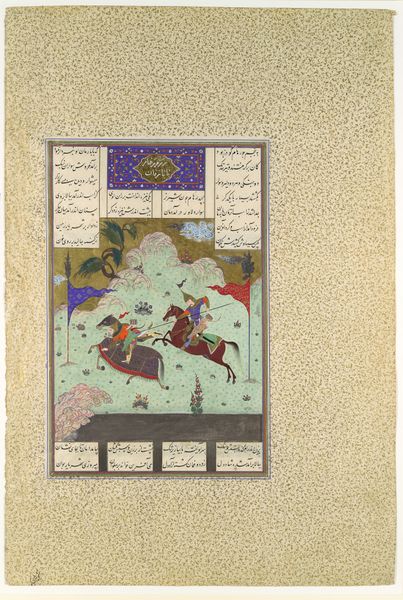

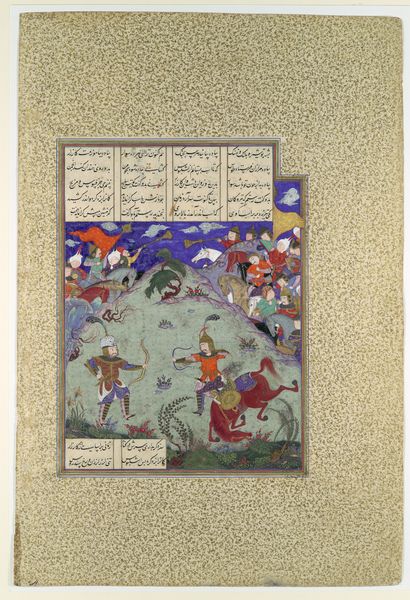

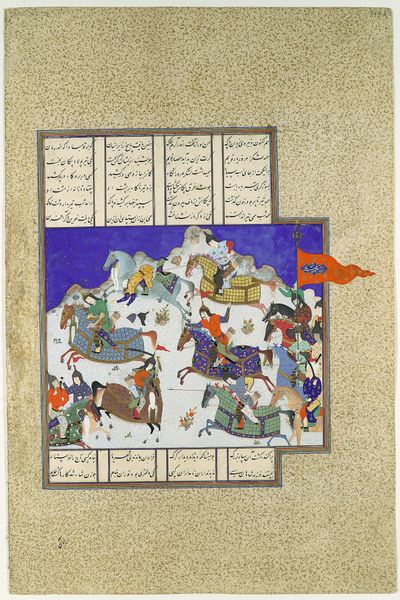

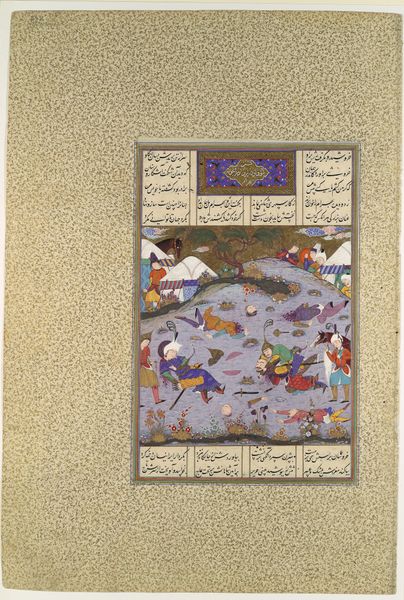

"Bahram Recovers the Crown of Rivniz", Folio 245r from the Shahnama (Book of Kings) of of Abu'l Qasim Firdausi, commissioned by Shah Tahmasp 1500 - 1555

0:00

0:00

tempera, painting

#

narrative-art

#

tempera

#

painting

#

asian-art

#

traditional media

#

figuration

#

horse

#

abstraction

#

men

#

islamic-art

#

history-painting

#

miniature

Dimensions: Painting: H. 9 1/4 in. (23.5 cm) W. 10 3/8 in. (26.4 cm) Entire Page: H. 18 3/4 in. (47.6 cm) W. 12 5/8 in. (32.1 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Examining "Bahram Recovers the Crown of Rivniz" from the Shahnama, commissioned by Shah Tahmasp around 1500-1555, we need to look at it beyond just an illustration of a historical tale. How was this object actually produced and consumed? Editor: Well, it's stunning! This tempera painting, a miniature, depicts such a dynamic scene, with so many figures and details crammed in! What can you tell me about this piece, particularly looking at the labor and social context surrounding its creation? Curator: Notice the meticulous detail achieved with tempera. Think about the workshops—the physical space, the hierarchy of labor. We aren't just seeing pigment on paper. We're witnessing the result of highly skilled artisans working under the patronage of a powerful figure. Who were these artisans? What were their lives like? Editor: So it’s about moving beyond admiring the surface and asking about the material conditions that allowed it to exist? Were these artists celebrated or considered more as anonymous laborers fulfilling a commission? Curator: Precisely. It's not enough to simply say, "This is beautiful." We have to ask *why* it looks the way it does. Consider the cost of the pigments, the preparation of the vellum, the years of training required. All of this reflects power structures and the allocation of resources. What impact did Shah Tahmasp's patronage have on the artists' lives and creative choices? Editor: I hadn't thought about it that way before; it gives me a whole new framework for thinking about the object. It encourages a broader understanding of both the artwork and its position in a socio-economic reality. Curator: And remember, this wasn’t just passively admired. It was actively used, likely for instruction or legitimation of the Shah's power. Its value extended beyond aesthetics. Its materiality is deeply embedded in its use. Editor: Seeing this as the result of material practices definitely enriches my perspective and has moved my thinking towards broader historical context. Thanks.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.