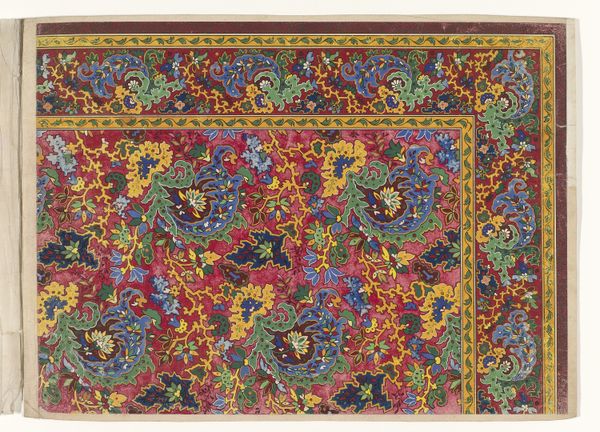

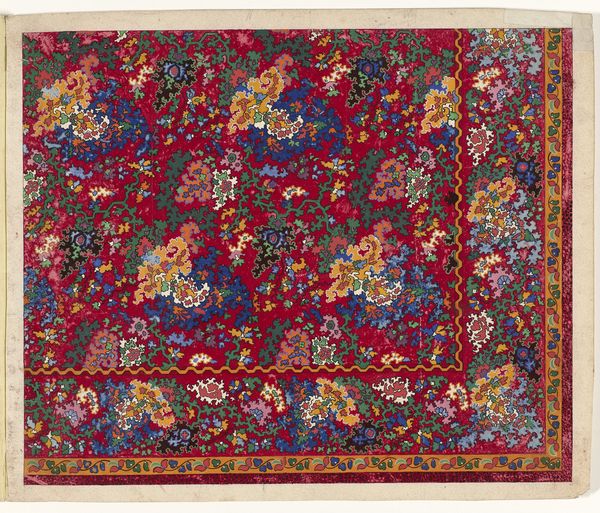

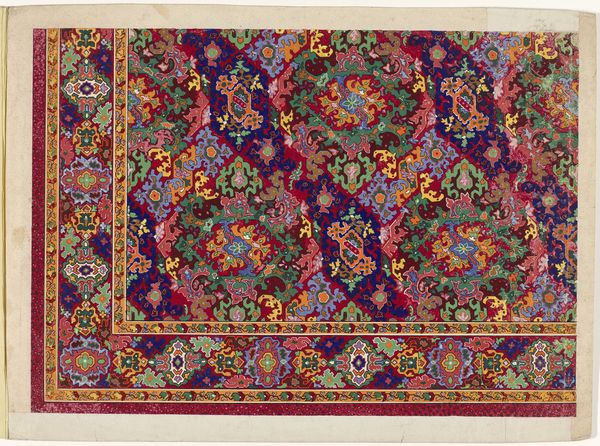

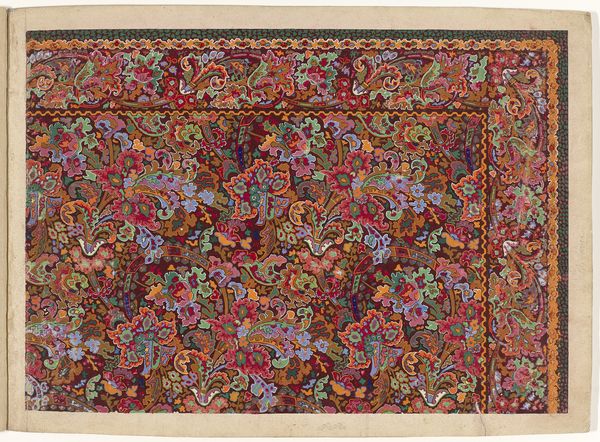

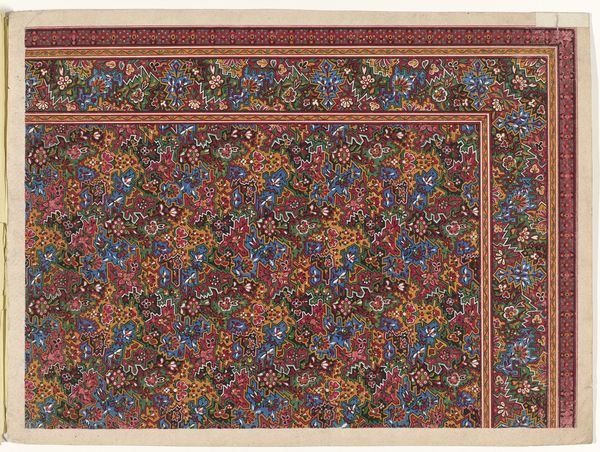

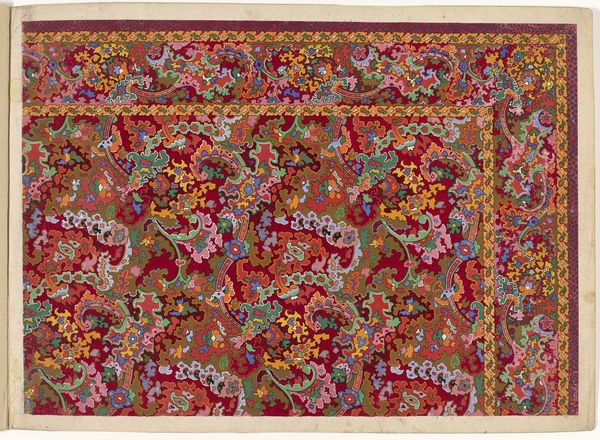

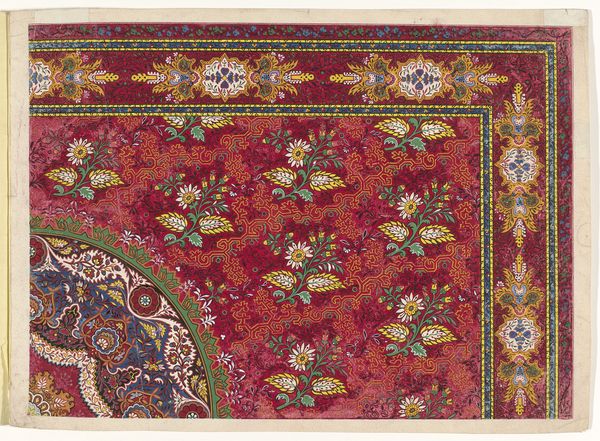

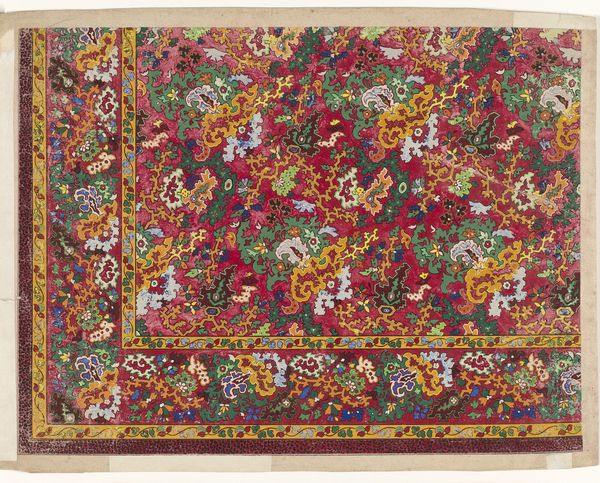

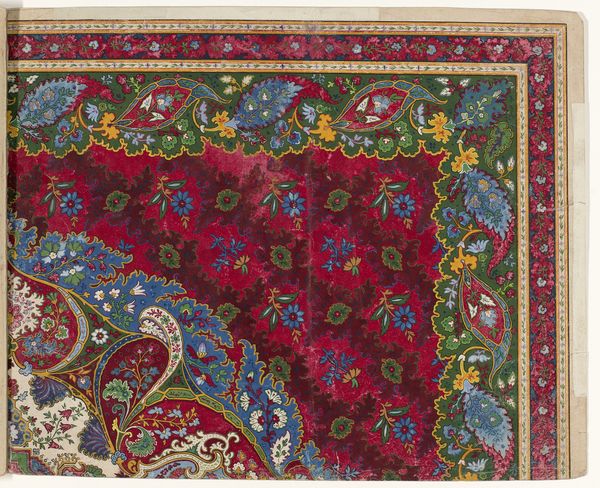

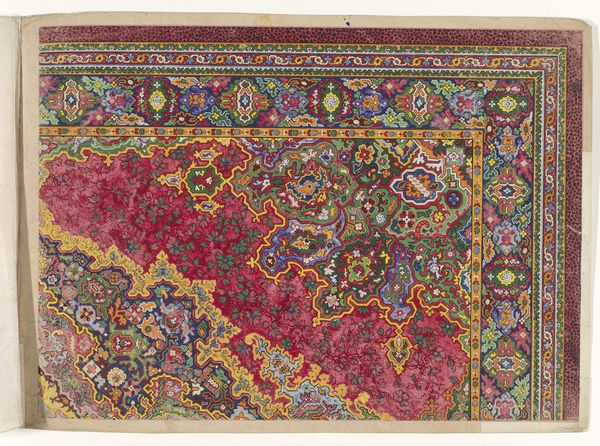

fibre-art, textile

#

fibre-art

#

naturalistic pattern

#

organic

#

loose pattern

#

textile

#

geometric pattern

#

abstract pattern

#

organic pattern

#

decorative-art

Dimensions: 112 1/2 × 90 in. (285.75 × 228.6 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

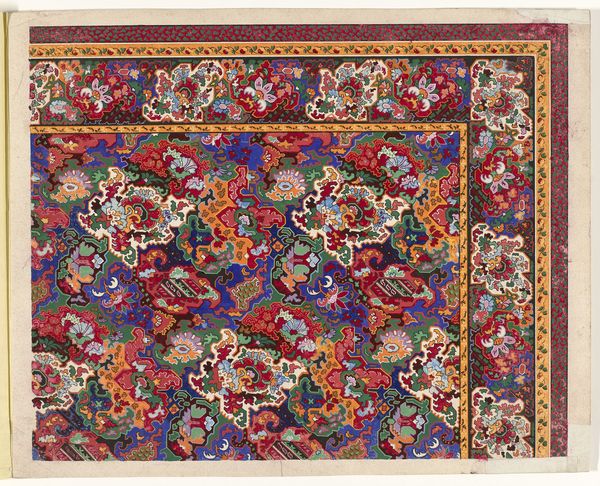

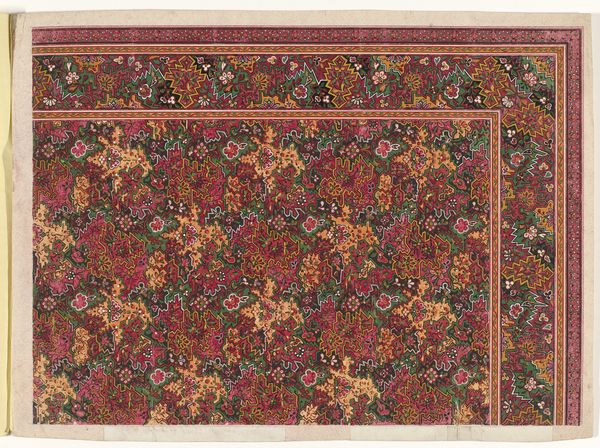

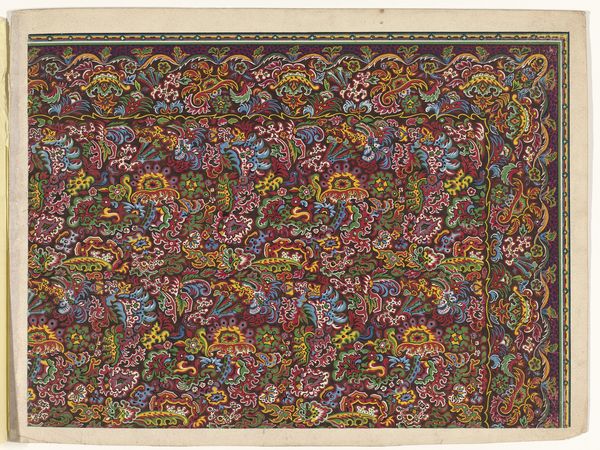

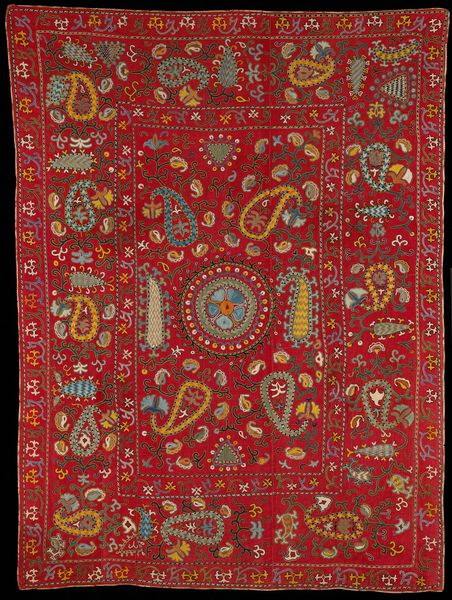

Curator: Here we have a “Carpet,” its creation is placed sometime between 1737 and 1745. This textile is part of the collection at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Woven with wool, it presents a mesmerizing field of floral patterns. What’s your first impression? Editor: Utterly enchanting! The density of blooms creates such a lush, almost overwhelming effect. The color palette, although rich, feels grounded, like a secret garden discovered after years of slumber. Curator: I think that "secret garden" idea is spot on. Tapestries and carpets, beyond their practical use, held symbolic importance in aristocratic society. This carpet may have acted as a kind of portable garden, representing power and refinement, where ownership equaled the control of nature’s abundance. Editor: It's intriguing to think of it as a controlled ecosystem. The precision of the geometric borders contrasted against the organic chaos of the floral interior really does emphasize that notion of control, doesn't it? Yet, even in that control, the artistry seems deeply intuitive, a conversation with, rather than a domination over, the natural world. Curator: Absolutely, and consider how a piece like this mediated social interactions. It might be unrolled for specific guests or displayed to convey a certain status. Textiles were highly prized goods, circulating within elite social circles and becoming statements of personal and familial power. The colors and patterns became their own kind of language. Editor: Do you see the pattern as language, something akin to codes and symbols? My first impression wasn’t especially academic – I reacted viscerally. It conjured memories of wandering through my grandmother’s rose garden, overwhelmed by scent and color… Did people at the time appreciate its pure beauty as well? Curator: It's important to remember that "beauty" is always a product of its time. While we respond emotionally to the work, people then had specific expectations. Skill, material value, adherence to particular design conventions, these all mattered in determining worth. Beauty was a calculated part of the visual culture that reinforced social standing. Editor: Right, of course. It makes one consider the distance between the intentions of the artist and how we view such objects centuries later. What was once functional and performative can now elicit such personal introspection. I feel almost guilty imbuing it with so much personal meaning! Curator: But that is exactly the magic of art! This textile embodies the past’s formal artistry but offers fertile ground for a dialogue with the present. Editor: A beautiful, unexpected collision between then and now, and I thank you for giving us insight on what this textile truly meant in its era!

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

This entirely hand embroidered textile was probably intended for use as a table covering. Such decorative cloths were highly prized and either covered or removed when the table was used. The embroidery was the work of Abigail Goodwin and her eldest daughter Anna-Maria. It took eight years to complete the project; beginning and end dates (1737 and 1745) are embroidered at each end of the carpet. Tragically, Anna-Maria died in 1743. For the following two years, Abigail continued the project on her own. Among other surviving carpets made during this period, this example is exceptional for its remarkably fresh colors. It is possible that it was never used given its association with Anna-Maria and her unfortunate early death.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.