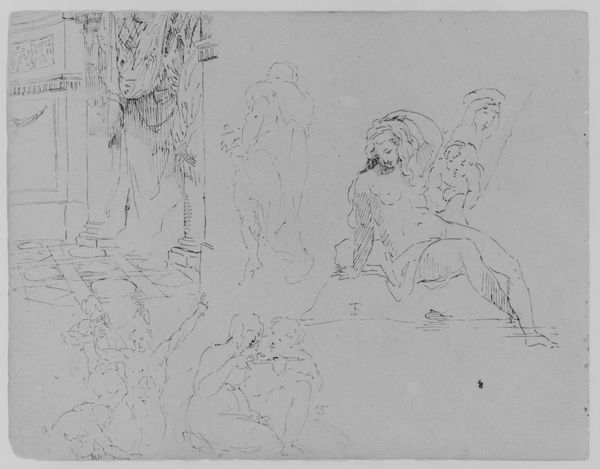

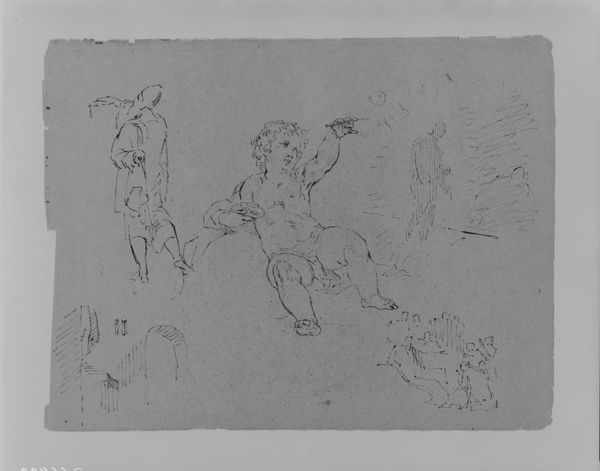

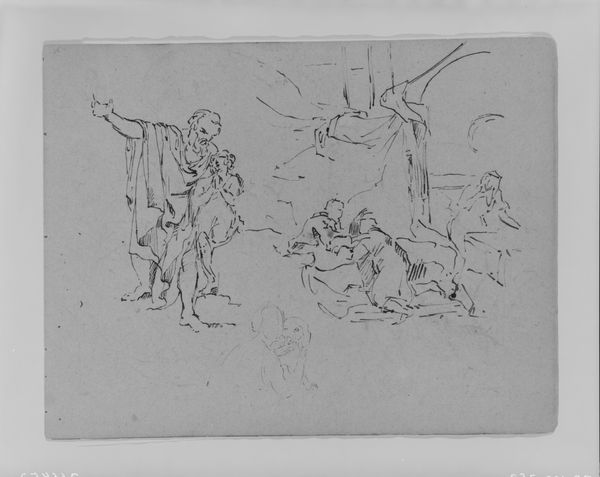

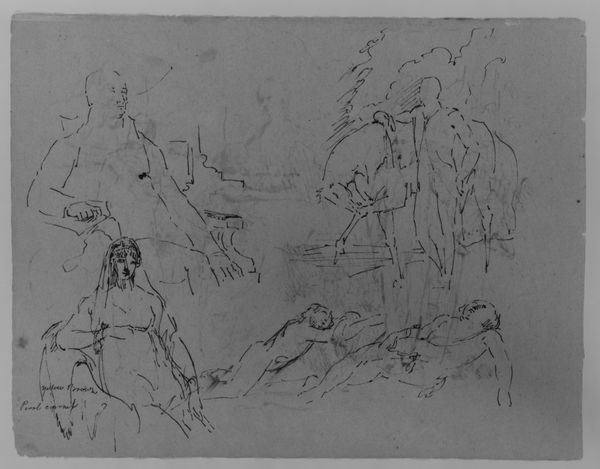

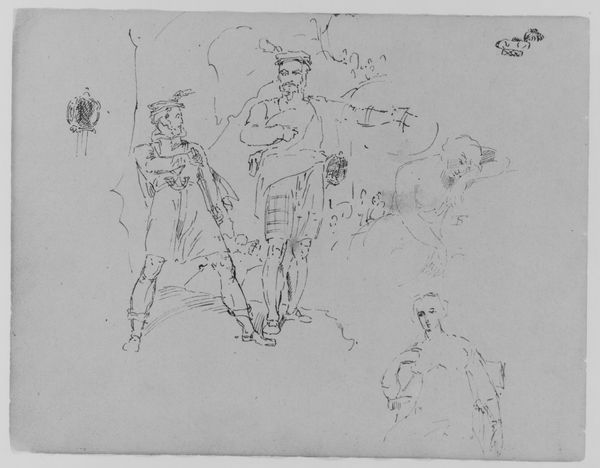

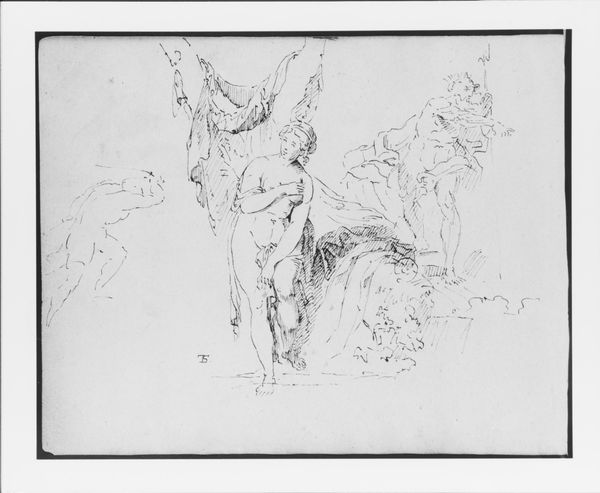

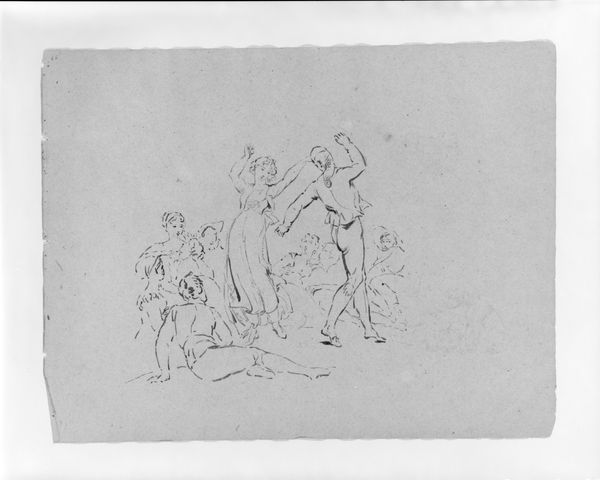

Man on Horseback with Standing Figure; Female in a Landscape (from Sketchbook) 1810 - 1820

0:00

0:00

drawing, pencil, pen

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

light pencil work

#

pencil sketch

#

incomplete sketchy

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

personal sketchbook

#

sketchwork

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

romanticism

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pencil

#

horse

#

men

#

sketchbook drawing

#

pen

#

sketchbook art

#

initial sketch

Dimensions: 9 x 11 1/2 in. (22.9 x 29.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: This is "Man on Horseback with Standing Figure; Female in a Landscape" a sketchbook page by Thomas Sully, dating from around 1810-1820, made with pen and pencil. It’s so delicate and ephemeral, almost like a fleeting dream. What do you see in this work? Curator: It's fascinating to consider the sketchbook not just as a repository of ideas, but a site of labor itself. These rapidly executed sketches are records of Sully grappling with form and composition. We can consider the material realities of its production, like the cost of paper, pencils, and even the time Sully dedicated to this pursuit. How do these economical lines hint at broader social relationships to you? Editor: I see them as experiments... Sully's trying different things out, playing with the relationship between the figures and landscape. Is it typical for artists of this period to use sketchbooks in this way? Curator: Absolutely. Sketchbooks offer unique insight into an artist’s process. He could be observing people around him. Considering his economic class and social context during the romanticism era, Sully would be surrounded by wealth that fuels a vision, but may have caused him constraints depending on his patron’s needs. How do you think the materiality of these drawings influenced their reception? Did people at the time view these quick sketches as having the same value as a finished painting? Editor: Probably not the same value, I imagine that these drawings provide unique value because they offer a window into Sully's process and methods for his bigger work. It almost flattens the hierachial divide between sketch and ‘finished’ work… Curator: Precisely! By exhibiting such intimate, process-oriented work, institutions invite viewers to contemplate not only the finished product but also the labor, materials, and decisions that shaped its creation. It challenges the romantic vision of the artist as divine creator and humanizes art making process by underlining the cost, material, labor and the consumption value associated with art works. Editor: I hadn’t thought about it that way before. Looking at art this way makes the whole art experience seem more accessible to me. Curator: And that’s what material analysis helps us do - bring art closer to real life and the production realities involved.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.