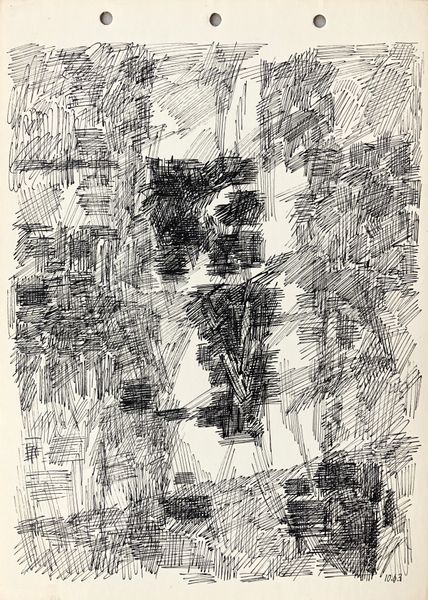

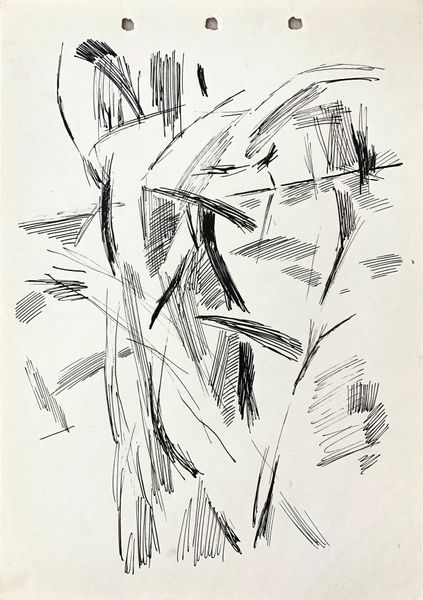

drawing, ink

#

portrait

#

17_20th-century

#

drawing

#

german-expressionism

#

figuration

#

ink

#

expressionism

#

line

Copyright: Public Domain

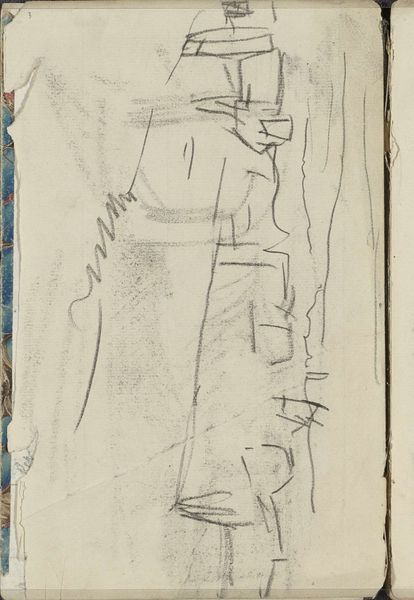

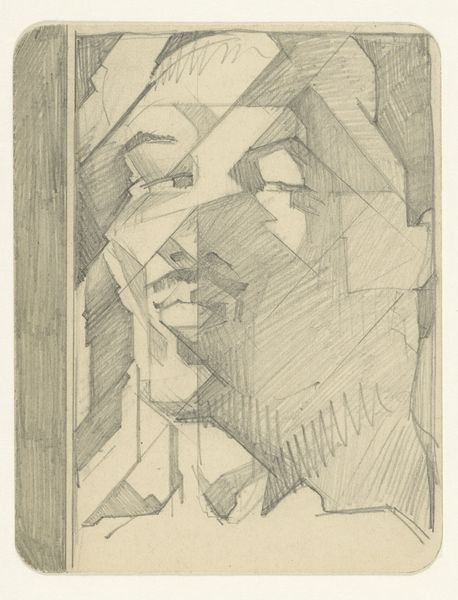

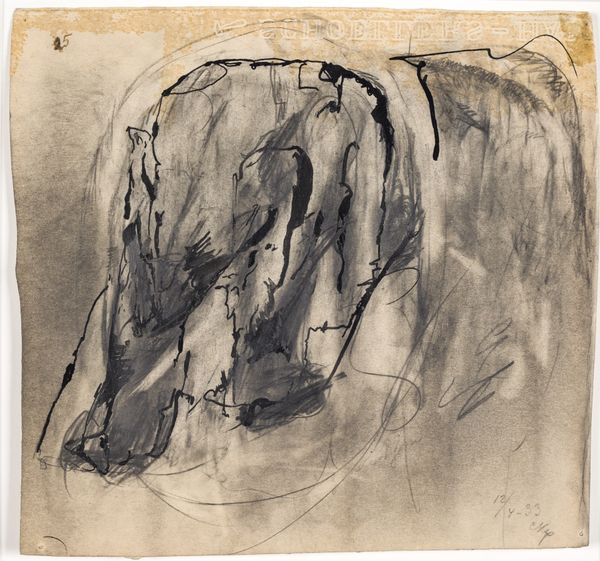

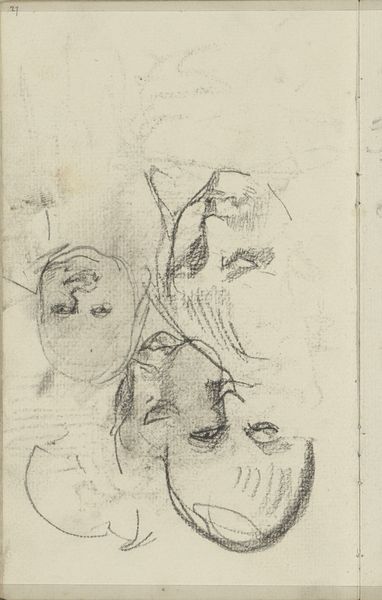

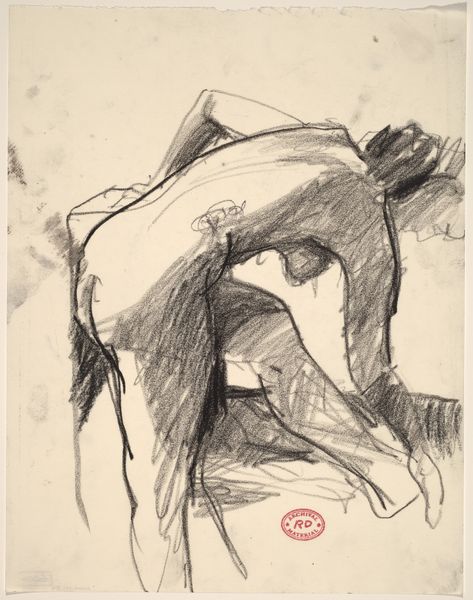

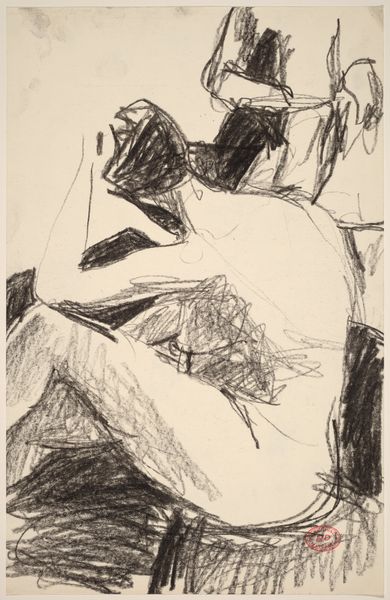

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner made this drawing of Erna with ink on paper sometime in the early 20th century. The strokes are so raw and immediate, like he’s trying to capture a fleeting thought. You can really see Kirchner working through the image, not trying to get it ‘right’ but being led by the process. Look at the lines around the eyes; they’re almost frantic, so thick and dark compared to the rest of the face. It gives the impression of someone who’s seen too much, or is weighed down by something. The mouth is just a few quick strokes, almost an afterthought, which makes me think about how much we communicate without saying a word. Kirchner's work reminds me of Francis Picabia who also embraced a certain kind of roughness and immediacy in their work. Both artists invite us to embrace the incomplete and the uncertain. These artists remind us that art doesn't have to be about perfect representation but can be about feeling, about the messy reality of being human.

Comments

stadelmuseum over 2 years ago

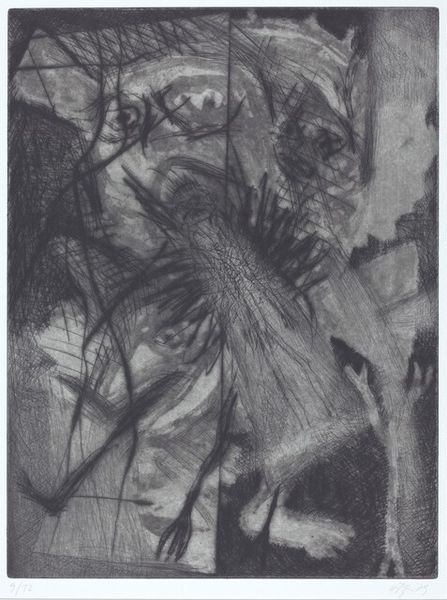

⋮

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner met his life companion, Erna Schilling (1884-1945), in Berlin in 1912. Various portraits from the early years of their relationship depict her striking face and severe bob hairstyle. In this reed-pen drawing, however, Kirchner seems less interested in the distinctive look of his girlfriend - which possesses neither grace nor charm - than in her state of mind. The long pen strokes look rapid and nervous, as do the few parallel curves describing the slight inclination of her head. Erratically rubbed parts indicate an eyebrow and the hairline emerging from beneath her hat, which is adorned with a few decorative tokens. The lowered gaze of her large dark eyes looks resigned in contrast to the nearby beams of light. Together with the firmly closed mouth, whose narrow lips are emphasised by two short superimposed lines, they express a profound sadness. After Kirchner had executed the reed-pen drawing, which essentially describes Erna's state of mind, he used a pencil to sketch in a conciliatory incorporation of the figure into the space. The interplay between the concentrated effect of the ink drawing in blue-grey ink and the light silver-grey of the pencil give the portrait a melancholy air.We know that Kirchner gave those around him great cause for concern at the time he created this drawing. Like Max Beckmann, Kirchner was in active service during the First World War and was discharged in 1915 because of mental illness, but was nonetheless haunted by the fear of being recruited a second time. Courses of treatment in sanatoriums in Königstein im Taunus and in Berlin were followed in 1917 by a first sojourn in Davos. Before he finally spent the longest period of his life here, among the mountains of Switzerland, he was admitted for ten months in the autumn of 1917 to the Sanatorium Bellevue in Kreuzlingen, on Lake Constance, where they attended to his health condition, which was considered to be incurable. It seems logical to regard the sadness expressed in Erna's portrait as a mirror of Kirchner's own state of health.The confiscations which were part of the 'degenerate art' campaign in 1937 under the National Socialists dramatically reduced the stocks held in the Städel collection. The donation of this and other drawings by Kirchner from the artist's estate, together with his works from the "Bequest of Dr. Carl Hagemann", today form a main area of focus on twentieth-century art at the Städel's Collection of Prints and Drawings.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.