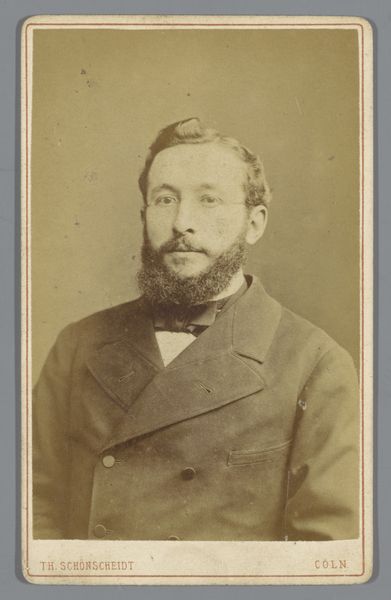

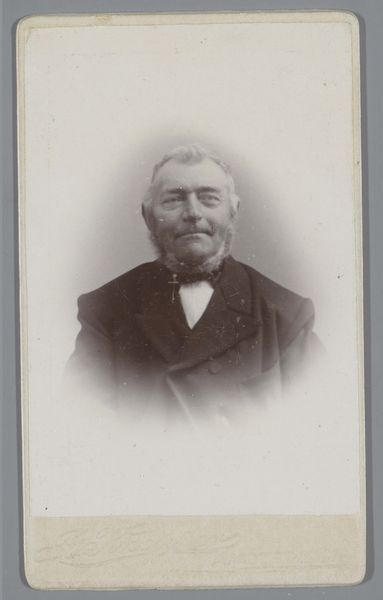

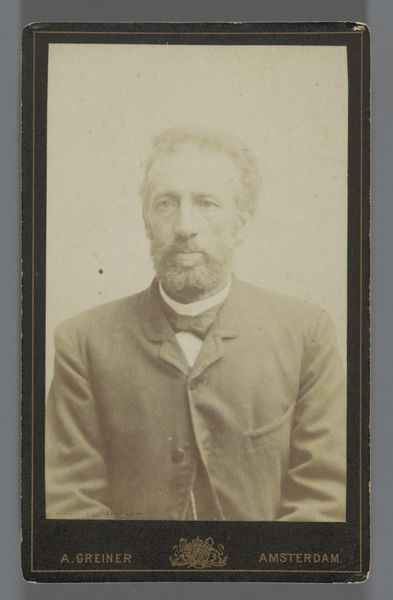

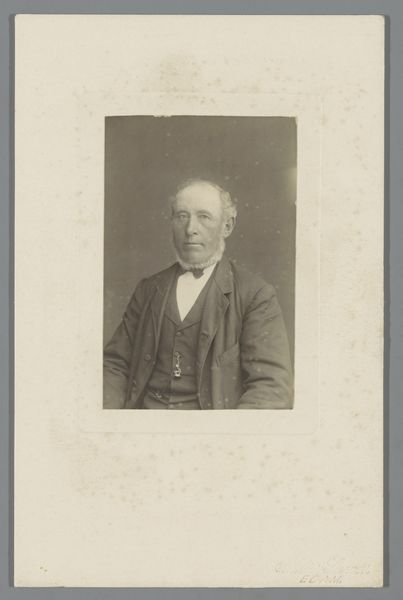

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

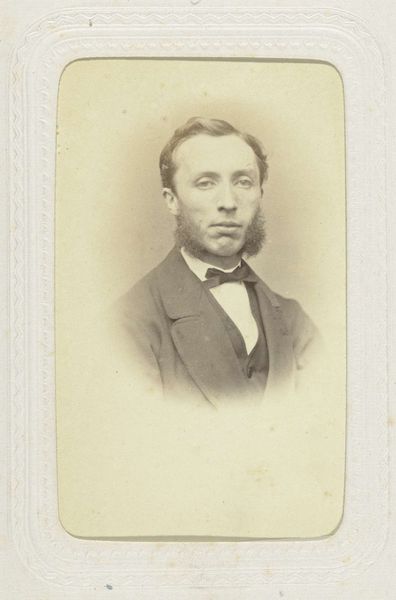

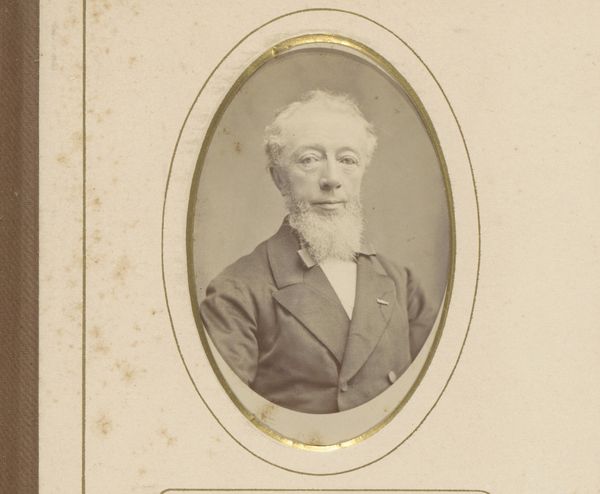

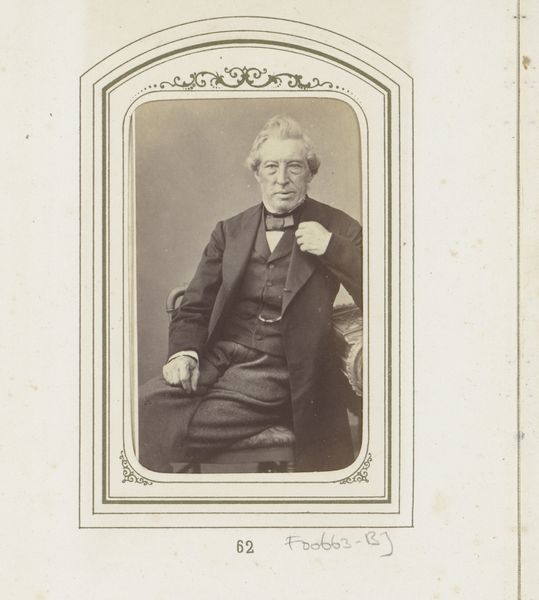

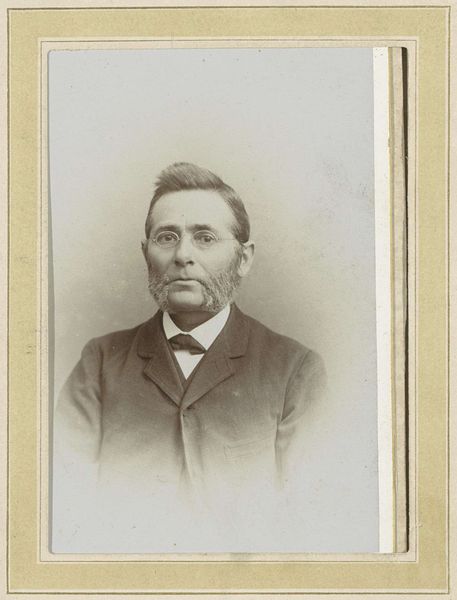

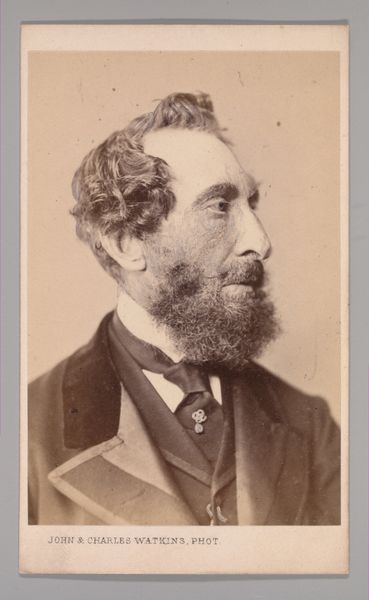

portrait

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

19th century

#

realism

Dimensions: height 96 mm, width 57 mm, height 102 mm, width 61 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is a fascinating image—a portrait of Samuel Coronel, possibly from 1878. It’s a gelatin-silver print, giving it that lovely, almost ghostly quality. It's so typical of 19th-century portraiture, quite formal, but I find myself wondering about the process involved in creating these early photographs. What can we say about it? Curator: For me, this image immediately speaks to the radical shift in art production that photography instigated. Before this, portraiture was the domain of painting, a luxury item dependent on highly skilled labor. Photography, even in its nascent stages, democratized image-making. How do you think this affected social structures? Editor: It must have changed the perception of who deserved to be represented. Suddenly, having your image captured wasn’t solely for the elite, even though there were still obvious class dynamics at play related to access and the technology itself. Curator: Exactly. And look closely at the materiality – the specific qualities of the gelatin-silver print. The textures, the subtle tonal gradations - they are a direct product of a specific chemical process, the application of a particular kind of labour. Think about the photographer, Staas. What does it mean for an artist's role when the creation of the image is so tied to industrial processes and scientific understanding? Editor: That's a great point! I suppose we need to think beyond traditional notions of artistic skill and authorship here. It's much more than simply someone pressing a button; it is about mastering a technology and perhaps responding to that technology itself, pushing it and seeing what it's capable of capturing. Curator: And influencing the broader understanding of representation. The image then becomes an object for widespread consumption and display, reproduced in multiples, shaping perceptions and narratives about identity and social standing in ways paintings couldn’t. Editor: I see, so it’s not just about the image itself but the means of production and how those material conditions transformed art and society at that time. Curator: Precisely!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.