Copyright: Public domain

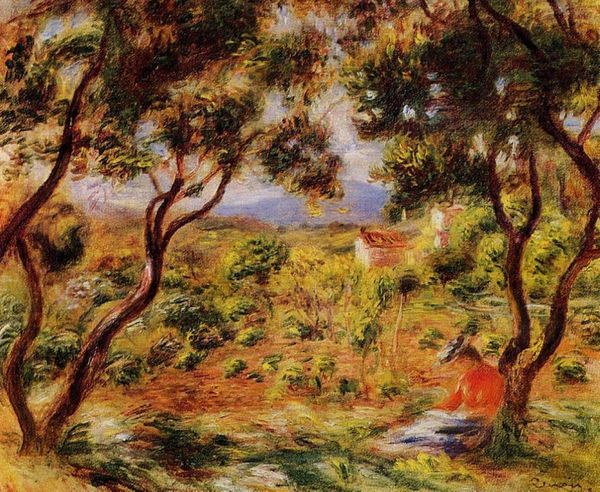

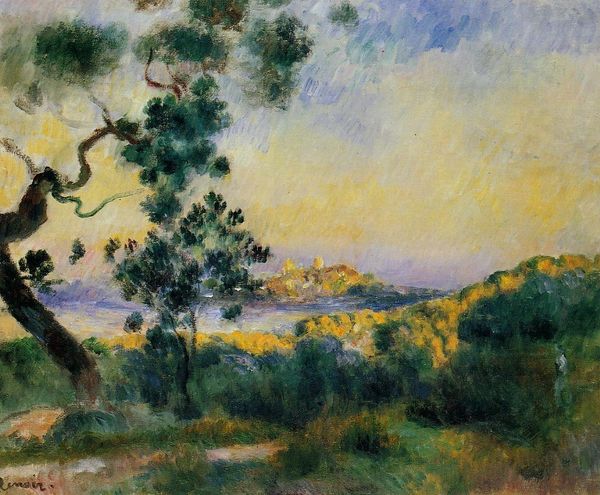

Curator: Editor: Here we have Renoir's "Landscape at Beaulieu," created in 1899, using oil paint. It really evokes the feeling of a warm summer afternoon. What do you make of this landscape? Curator: I see a piece deeply invested in the physicality of paint. Look at how Renoir builds up the surface, the visible brushstrokes. The landscape becomes less about representation and more about the act of applying pigment to canvas. Consider where the pigments came from at that time, their production, and their cost. These materials shaped the very possibilities of painting itself. Editor: That's fascinating! So, you're saying the material is more important than what is depicted in the painting? Curator: Not necessarily more *important,* but inseparable. Think about the labor involved in creating this artwork. The preparation of the canvas, the grinding of pigments, the act of plein-air painting itself—these are all physical processes rooted in a specific social and economic context. Also, where would paintings like this hang, and for whom, during this period? The means of artistic production cannot be separated from its cultural use and valuation. Editor: It definitely shifts my perspective. It makes me think about how reliant he was on those materials, and on the industrial processes of making and selling those paints. I hadn't really thought about that aspect before! Curator: Exactly! By examining the materials, we start to unpack the web of social relations embedded within the artwork. The finished painting isn’t just an image; it’s the culmination of numerous material and labor-related processes. Editor: That really provides a new lens for appreciating art; from the consumption of paint to social contexts that enabled the artist to make it. Curator: Indeed. It is all deeply entangled.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.