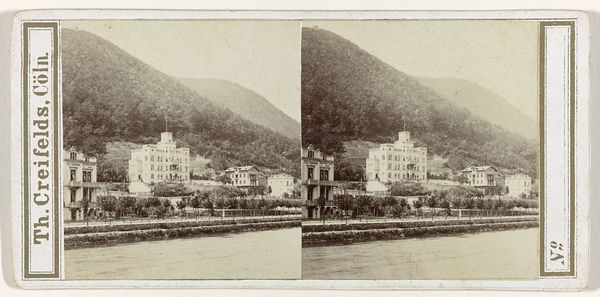

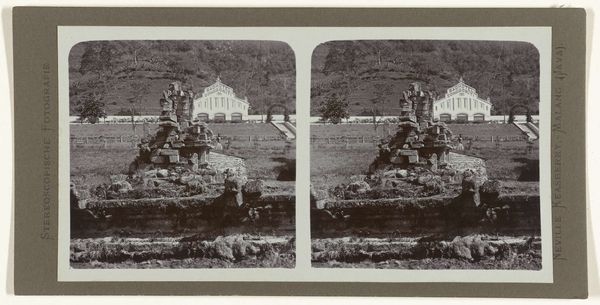

Kerk van de Heilige Alexandra aan de oever van de Lahn in Bad Ems, Duitsland 1874

0:00

0:00

daguerreotype, photography, architecture

#

landscape

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

coloured pencil

#

architecture

#

realism

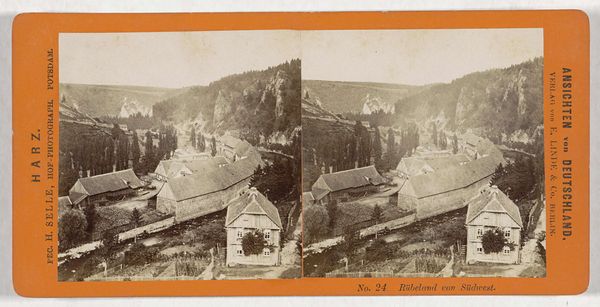

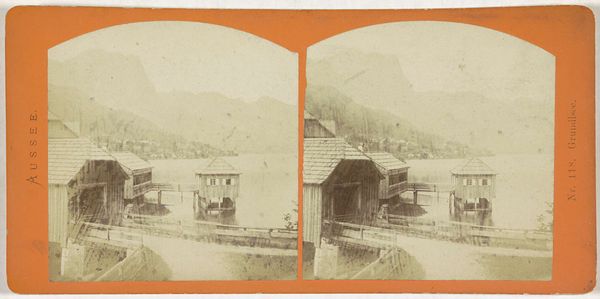

Dimensions: height 89 mm, width 180 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: What a remarkably still image. It feels incredibly…contained, somehow. Editor: Well, let's dive into it. This is a daguerreotype by Edmund Risse, created around 1874. It's titled "Kerk van de Heilige Alexandra aan de oever van de Lahn in Bad Ems, Duitsland," or in English, "Church of the Holy Alexandra on the banks of the Lahn in Bad Ems, Germany". A wonderful example of how architecture intersects with the rise of photography as a new means of visual representation. Curator: That river almost looks like quicksilver. The texture in that body of water certainly seems manipulated and refined by a laborious photographic practice of the era. Was he trying to give a Romantic sheen to the church through his treatment of materials? Editor: Perhaps. Bad Ems was a popular spa town and resort for the European elite in the 19th century. Capturing images like this one helped promote the town's beauty and tranquility, enticing visitors and bolstering the local economy. It presents an idealized version of the area’s attractions to lure people in and influence travel culture at the time. Curator: Right, there’s also this stark juxtaposition of architectural detail, like the Russian-style domes, against a rather industrial-looking building on the periphery that must’ve been of the region. The building behind reminds me of mass housing but feels quite disconnected and strangely desolate—which makes it rather modern. I’m intrigued by the tension he creates between high culture and this emerging utilitarian built environment. Editor: That’s a perceptive observation! And note how the architecture of the church imitates that in Russia at a time when Russians frequented such resort locations throughout Europe. It catered to a specific social group within the wealthy visitors to the town and reflected the global mobility of aesthetics. The very act of commissioning, producing, and disseminating these stereo cards participated in an elaborate exchange between artists, patrons, and a public eager for visual documentation of travel and leisure. Curator: So it was like an early postcard. I still return to this tension in terms of material, something between record and pure invention. Editor: Indeed, that balance informs much of 19th-century landscape photography. It documents, yet subtly promotes cultural narratives and tourism—an intriguing dynamic, wouldn't you agree?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.