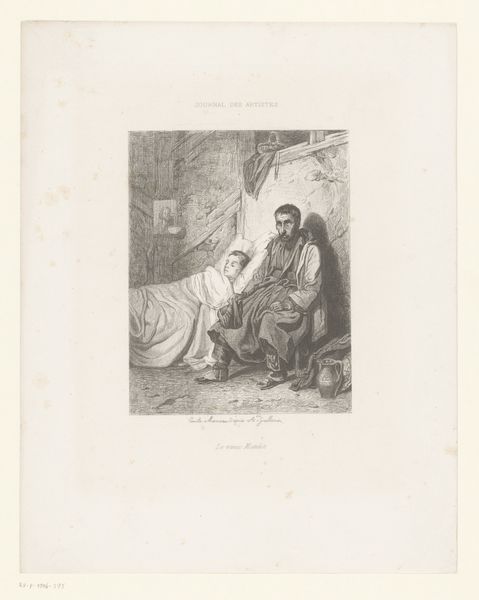

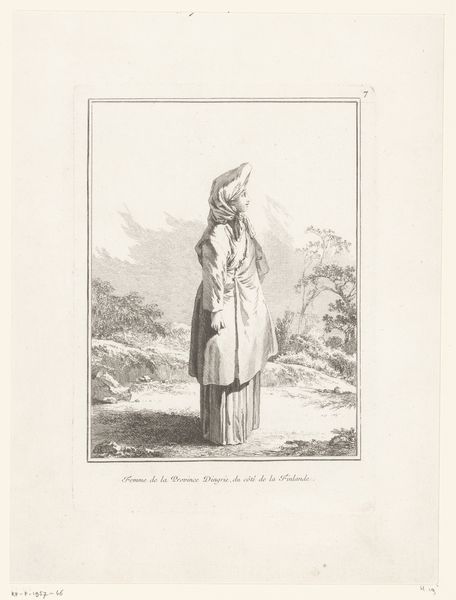

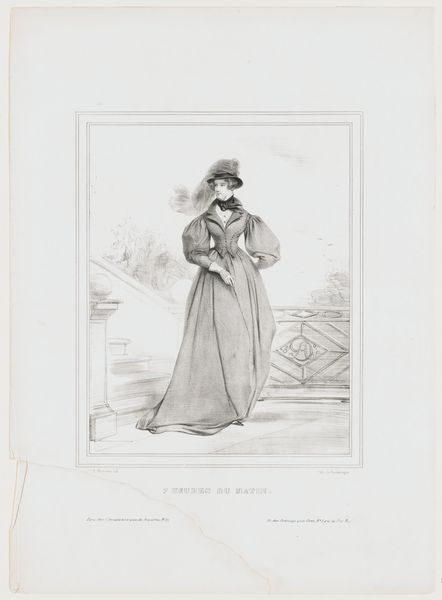

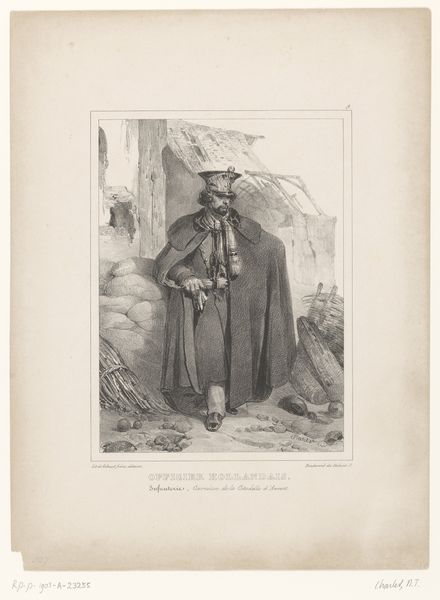

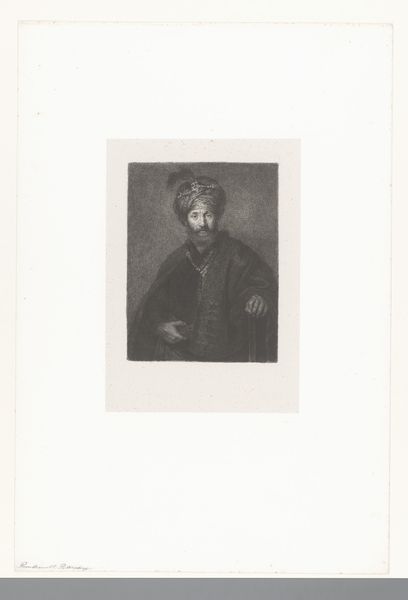

engraving

#

portrait

#

old engraving style

#

orientalism

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 304 mm, width 217 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have an engraving, dating from around 1838 to 1841, titled "Portret van Mahmud, sultan van het Ottomaanse Rijk," or "Portrait of Mahmud, Sultan of the Ottoman Empire." It depicts the Sultan in a somewhat theatrical pose. It's compelling, but what are we to make of a Western artist portraying an Eastern ruler this way? Curator: That’s the crux of it, isn’t it? This work reflects the rise of Orientalism in Western art, where the "Orient" became a site of fantasy and projection. While claiming realism, engravings like these helped construct and reinforce Western power dynamics. Who controlled the image, and thus, the narrative? Editor: So, even though it’s called a portrait, it’s not necessarily about accurately depicting the Sultan? Curator: Accuracy wasn't the primary concern. The image served a purpose, to depict a powerful 'other' within a framework accessible and appealing to a Western audience. Note how the artist uses familiar visual tropes: regal pose, luxurious textiles, hinting at exoticism. Consider what this image would communicate to the European public, both about the Sultan and about Europe's place in the world. Editor: It's almost like the engraving is saying more about the artist and his audience than it is about Sultan Mahmud himself. I’m curious how people perceived images like these in the 19th century. Curator: Exactly. It forces us to confront the biases inherent in how cultures represent one another, even with supposedly objective mediums like engraving. Images are never neutral; they participate in broader power structures. Editor: Thinking about the politics behind images helps me understand this work beyond just the visual. Thank you. Curator: Indeed, questioning representation keeps the past alive, so we do not repeat history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.