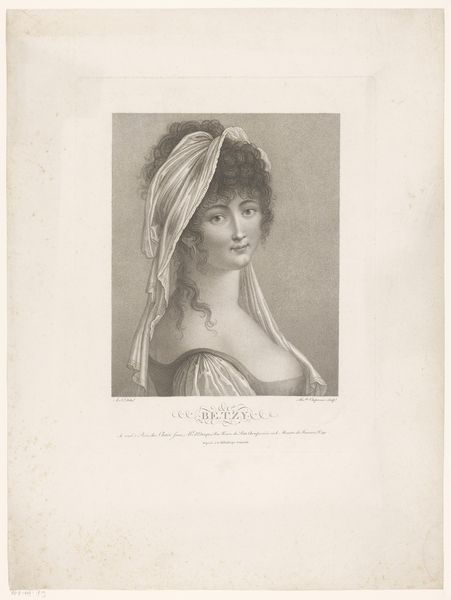

drawing, etching, pencil, engraving

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

etching

#

pencil sketch

#

figuration

#

pencil drawing

#

romanticism

#

pencil

#

pencil work

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 543 mm, width 362 mm

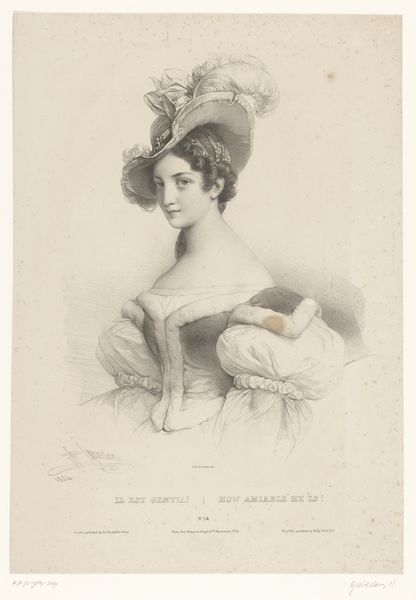

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this is Henri Grevedon’s "Portret van Juliette Récamier," made in 1826 using etching and engraving. It strikes me how delicate it is, the way the light and shadow define her face. What's your take on this portrait? Curator: Well, let's start with the materiality itself. Etching and engraving – these processes weren't just about reproducing an image. They were laborious, involving skilled artisans and specific technologies. Consider the social context: who had access to these printmaking workshops? Who controlled the means of distribution? Was Grevedon using these traditional print methods in response to newer forms like lithography? Editor: That's interesting, I hadn't thought about the actual physical work that went into it. The processes seem to reflect a certain emphasis on refinement. Does that speak to societal values at the time, maybe relating to consumption or class? Curator: Absolutely. The detailed rendering of Juliette Récamier's dress and the cushion she leans on – those details signal wealth and status. Romanticism often focused on individual expression and emotion, yet here we see it mediated through the material constraints and the economic realities of image production. This wasn't just about celebrating the sitter; it was also about showcasing the engraver’s skill and the technologies behind printmaking. Editor: So you are seeing beyond the face, to a whole world of production and labour? What about Romanticism being the style attached to it? Curator: Right, it challenges this view when we bring into question the accessibility of art materials. Not all of this image’s ‘world’ was equal! The mode of production makes Romanticism exclusive. The image is a luxury item produced with complex economic structure behind it, accessible for certain demographics, which contradicts its purported theme. Editor: I see what you mean. Thinking about the process, materials, and who controlled them gives the artwork a different weight. Curator: Exactly. Looking at art through a materialist lens offers new questions and interpretations, often disrupting conventional assumptions about art history. It also challenges those established stylistic boxes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.