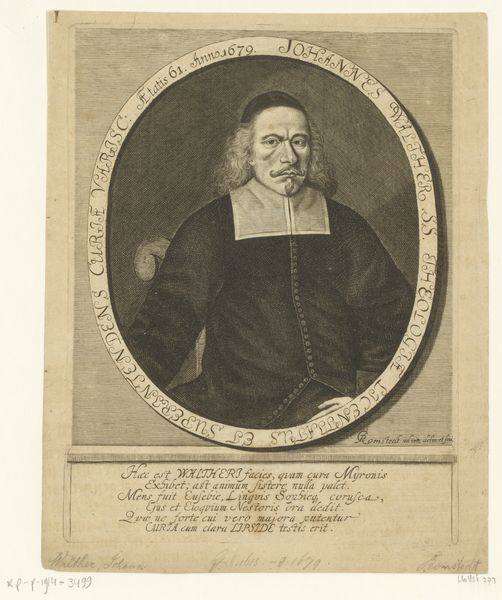

print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

old engraving style

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 136 mm, width 84 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this is Johann Christoph Boecklin’s "Portret van Martin Luther," a print from after 1697. It’s striking how Luther’s gaze feels so direct, even in this small engraving. What significance do you see in representing Luther in this way, especially so long after his death? Curator: This portrait, made well after Luther’s death, underscores his continuing symbolic power. Consider the cultural landscape: after 1697, religious identity was still intensely politicized. Boecklin's print isn't just a likeness; it's a political statement meant for public consumption. Editor: A political statement? In what way? Curator: Think about printmaking as a medium. It's inherently reproducible, easily disseminated. A portrait like this could be distributed widely, reinforcing Luther's image as a key figure of Protestant identity, thus subtly challenging Catholic authority and potentially stoking sectarian tensions. How does the inscription contribute to that political message? Editor: It reads “Living, I was your plague, Dying, I shall be your death, O Pope.” So, pretty blatant! This makes me wonder about its target audience. Were these images primarily for private devotion or for wider ideological persuasion? Curator: It's likely a mix. While personal faith was central, public demonstration and assertion of religious affiliation held social and political weight. Disseminating Luther’s image served to fortify a collective Protestant identity and memory, thus publicly contesting Catholic hegemony. Boecklin clearly understood art's ability to shape history and memory. Editor: I never thought about a simple portrait functioning like that, almost like propaganda! Curator: Indeed. It shows how art, especially in the form of a reproducible print, was instrumental in shaping and disseminating religious and political narratives, even long after the figure’s lifetime. It prompts us to question how images actively create historical realities and consolidate cultural identities.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.