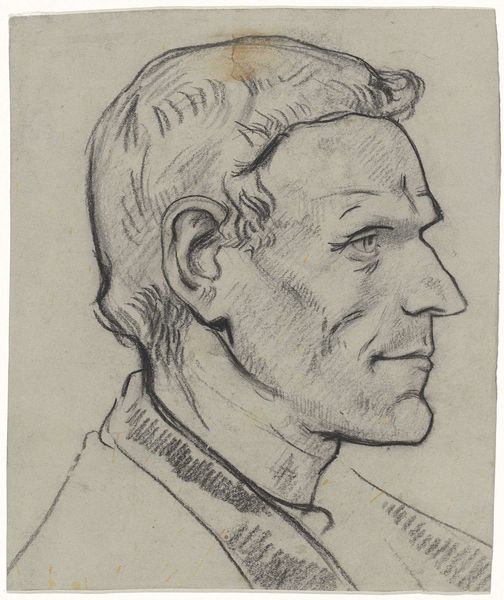

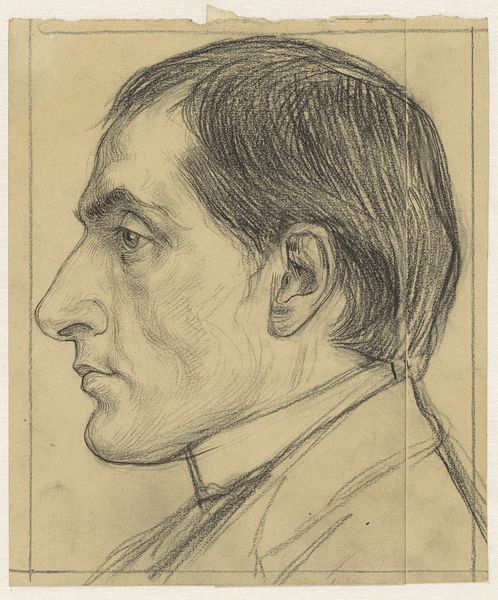

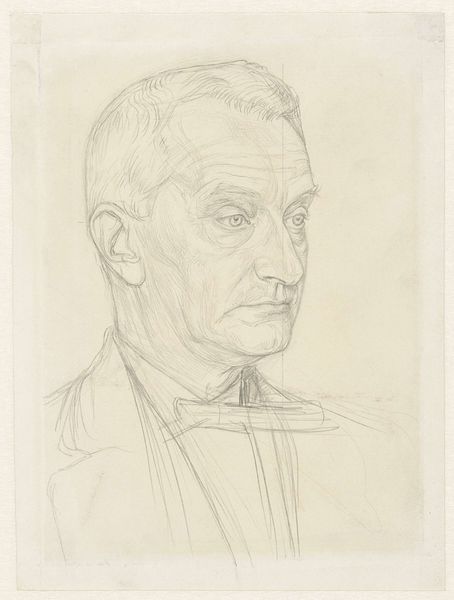

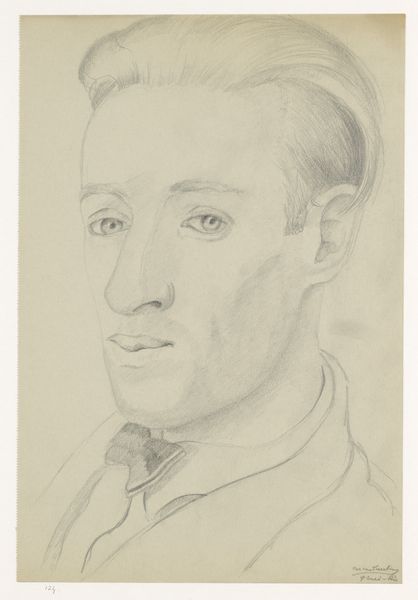

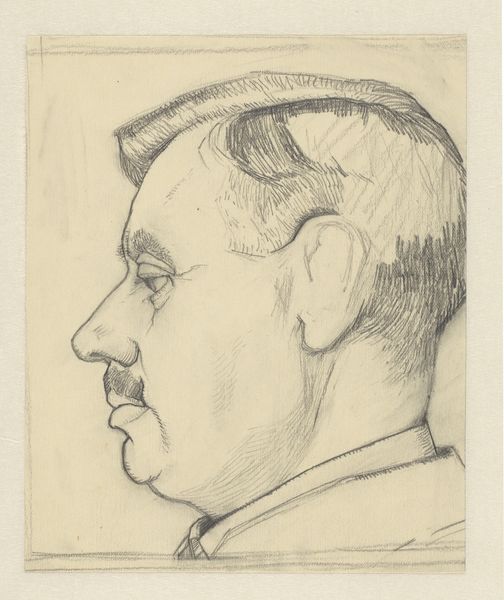

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

#

pencil

#

academic-art

#

realism

Dimensions: height 220 mm, width 165 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Richard Roland Holst’s “Head of a Man from Laren,” created in 1892, a pencil drawing. The precision of the lines makes me think of someone recording details for… posterity, maybe? It feels very formal in its presentation. What’s your take? Curator: My focus shifts to the materiality itself. Holst’s choice of pencil, a relatively accessible medium even then, speaks to the democratization of art production. Laren, as an artist’s village, complicates this further. Were these images meant to be exclusive fine art or, as a portrait, something more vernacular and accessible to its subject? Consider also the labour; a drawing like this, especially the delicate pencil work visible in the Rijksmuseum digital image, still required considerable skill and time. What purpose did that labour serve? Editor: So you’re looking beyond just the *who* and focusing on the *how* it was made and for whom? That's a great point. It really forces you to think about the artistic process less in terms of inspiration, and more in terms of… work. Curator: Precisely. What does this “academic art,” the portrait as genre, really do? Does it memorialize labor or obscure it? Is Holst documenting a particular individual or reinforcing ideas about rural identity within an emerging urban art market? These are the material questions the work raises for me. Editor: That's helpful. Looking at the details – the precise rendering, the sitter’s gaze–in combination with Holst’s access to materials makes it seem more than just a quick sketch. It suggests an intention that involves a public or, at least, a record beyond the purely personal. I see so much more than just the face now. Curator: Indeed. Thinking about process, materiality, and social context unveils new facets in even the most traditional of subjects.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.