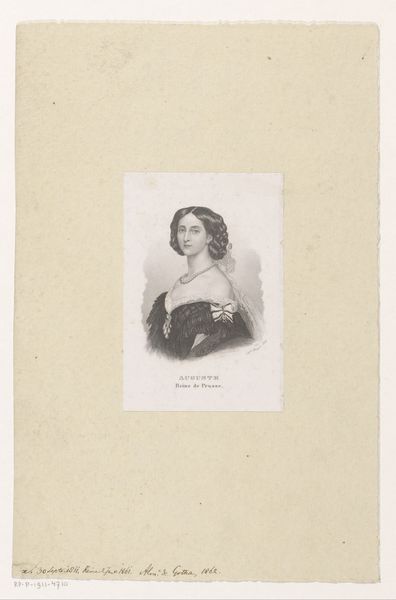

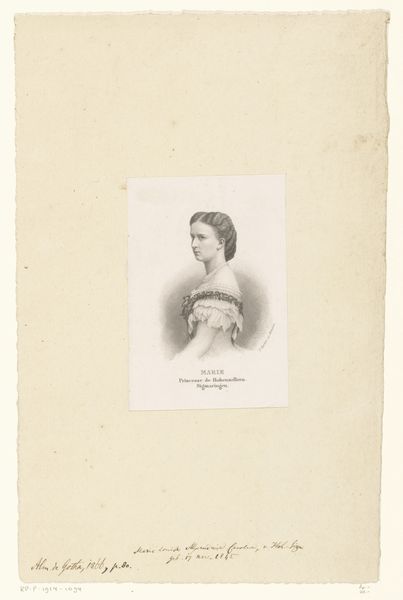

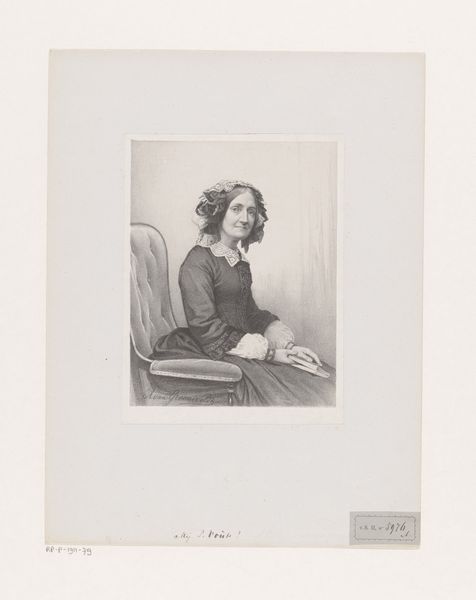

drawing, print, engraving

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil work

#

engraving

#

realism

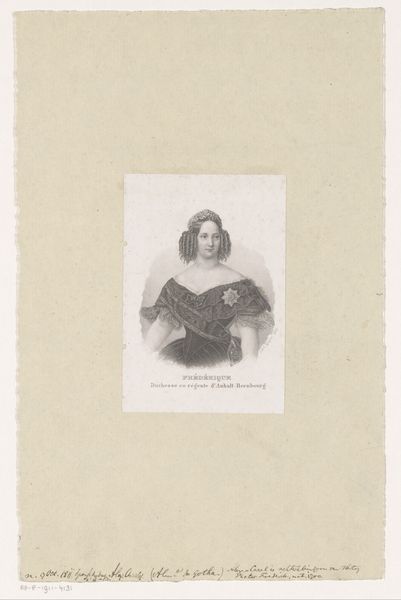

Dimensions: height 106 mm, width 73 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: What a delicate image. The "Portret van Amelia van Bourbon," attributed to Carl Mayer, residing here at the Rijksmuseum. The details state it was created sometime between 1834 and 1868, seemingly using pencil and engraving techniques. What is your first impression? Editor: A study in greyscale and restraint, I'd say. Her pose and attire suggest nobility, of course, but there's something in her expression that hints at a more complex inner life, perhaps reflecting the turbulence of the period. Curator: Agreed. It’s fascinating how Mayer blends what appear to be mechanical reproduction techniques with the human touch of a pencil sketch. Prints and drawings like these made portraits more accessible to a burgeoning middle class. It makes me wonder about the conditions in Mayer's workshop. Editor: That accessibility is key. Representation was shifting. To have one's likeness disseminated so widely… consider the implications for women, especially noble women, whose identities were so tightly bound to image and presentation. This portrait of Amelia then serves as evidence in the power structures related to Bourbon and the broader socio-political climate. Curator: It is striking to consider the physical labor. Engraving demands precision, the pencil allows for nuanced details on her face and clothing. What paper was used? Where did the materials come from? There is an economy inherent in image making that frequently goes unaddressed in work such as this. Editor: Precisely, and in what ways does her image play into or defy societal expectations of femininity and royalty during this time? What expectations are perpetuated, what new desires are created? I’m curious to know more about Amalia’s life, her position in court, how much agency she had over this representation. Curator: Examining art beyond its aesthetic qualities, dissecting its construction, offers new layers to interpret our collective and individual narratives. The work, material processes and implications—a valuable exercise to put these items in our shared world. Editor: Indeed. And through this layered approach, it’s no longer a static image, but a document alive with the complexities of its time, inviting a critical engagement with history and representation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.