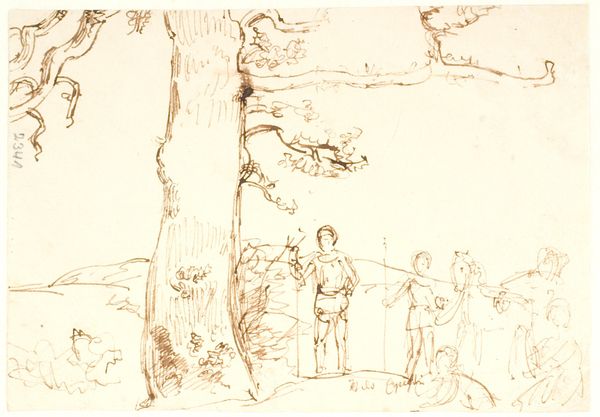

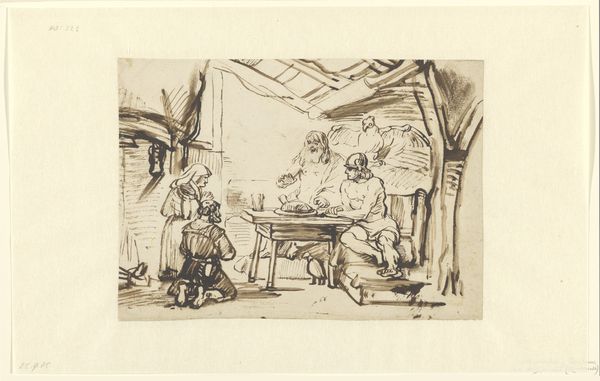

Jacob and Esau (recto); Head of a Young Woman Asleep (verso) 1647 - 1678

0:00

0:00

drawing, paper, ink, pen

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

#

ink painting

#

dutch-golden-age

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

paper

#

ink

#

pen

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: 94 × 156 mm

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have a drawing by Samuel van Hoogstraten, a Dutch Golden Age artist. It's entitled "Jacob and Esau," and dates to somewhere between 1647 and 1678. Editor: My first impression is how delicately the artist handled the ink; it's almost ethereal. The washes create a subdued and dreamlike atmosphere, despite the narrative scene depicted. Curator: It's interesting you say that. Hoogstraten, a student of Rembrandt, really manipulates the materiality of ink and paper. Consider how he utilizes varied line weights to create depth, essentially crafting an illusion. Also note that the drawing appears to have another, softer, drawing on the reverse: "Head of a Young Woman Asleep." That detail of a work on each side shows how paper, at the time, would have been utilized as a valuable commodity. Editor: Absolutely, and beyond its value as a commodity, paper acts as a veil to another world, literally so in this case. Focusing on the primary image, the narrative, we have a poignant rendering of the story of Jacob deceiving Isaac. It shows the transfer of a birthright for material sustenance. Notice the father seems frail in his reclined pose and the symbolism behind the outstretched hands between father and son—almost echoing depictions of the Christian blessing. Curator: Right, you point to the central transaction happening in this biblical scene, a foundational story, where, as we know, Jacob steals Esau's birthright. It also brings to mind questions of labor and the relationship between man and nature, as well as access to natural resources. The figures aren't simply in a space; they actively extract, negotiate, and manipulate within it. Note also the animals as they graze, passively unaware. This shows the economic backdrop to Hoogstraten's work. Editor: Agreed. But beyond the context of resources and economics, I'm drawn to the familial conflict played out through the symbolism. It’s about familial duty, and inherent destiny questioned—it speaks volumes about humanity's relationship with the divine, our desires, and deception. Curator: Well, this piece provides a valuable peek into Hoogstraten's technique. Thinking about his engagement with paper and pen as technologies in early modern Holland helps to really understand art and commerce. Editor: It’s a reminder, perhaps, of art's ability to not just capture moments but to distill timeless emotional struggles into easily-understood symbols.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.