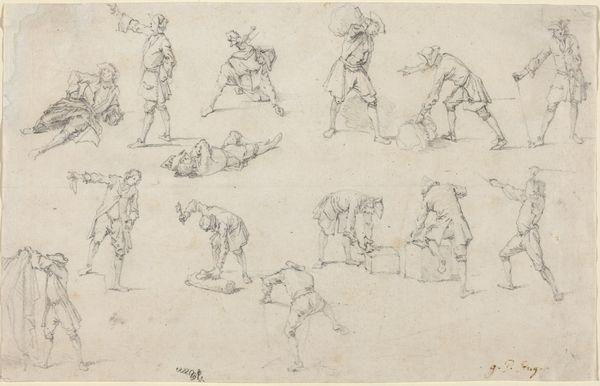

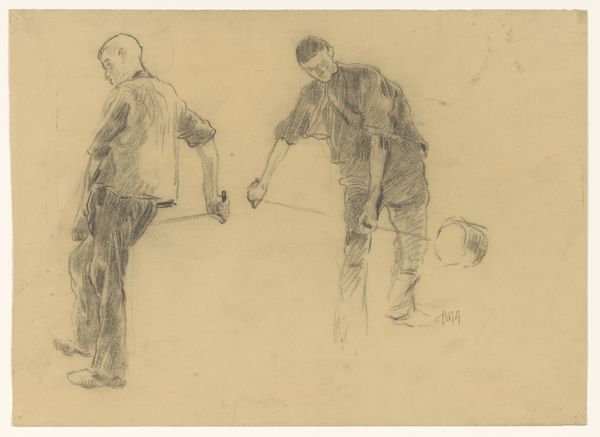

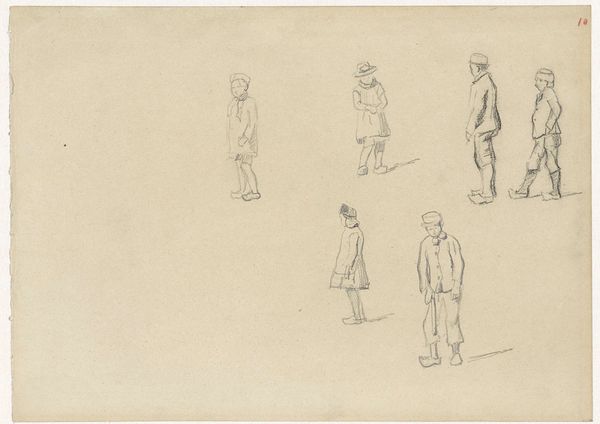

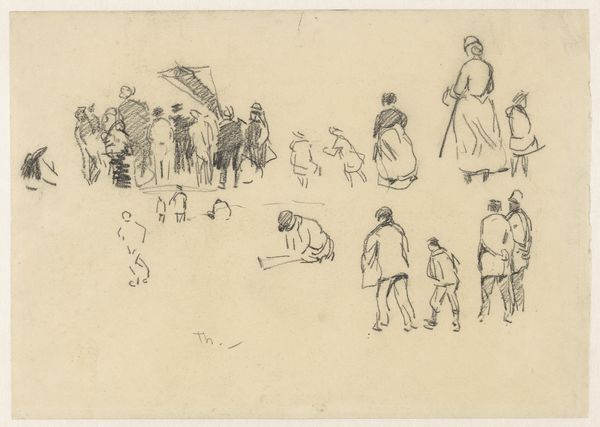

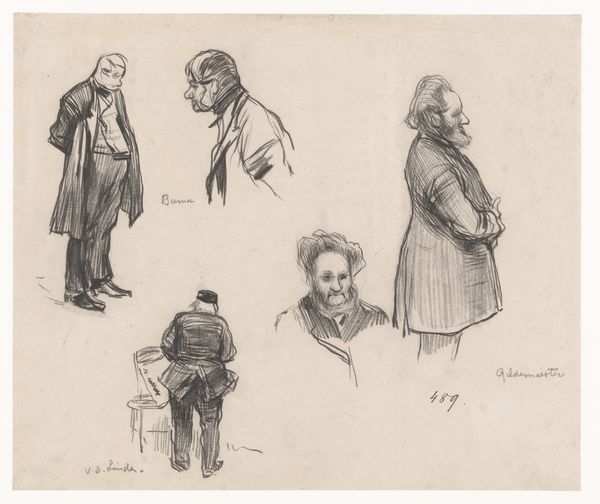

Studieblad met schetsen van een spittende arbeider 1871 - 1906

0:00

0:00

pieterdejosselindejong

Rijksmuseum

drawing, pencil, graphite

#

drawing

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

pencil

#

graphite

#

genre-painting

#

academic-art

#

realism

Dimensions: height 294 mm, width 457 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

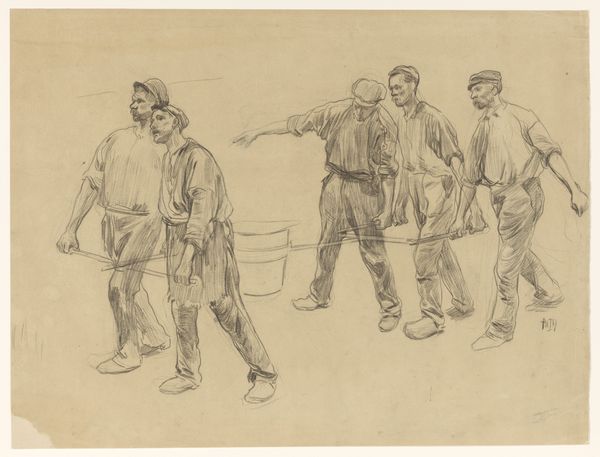

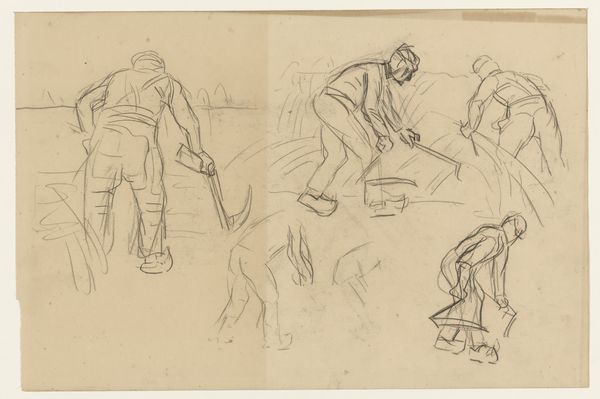

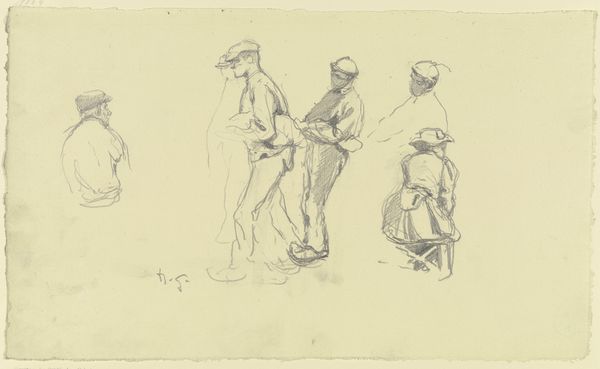

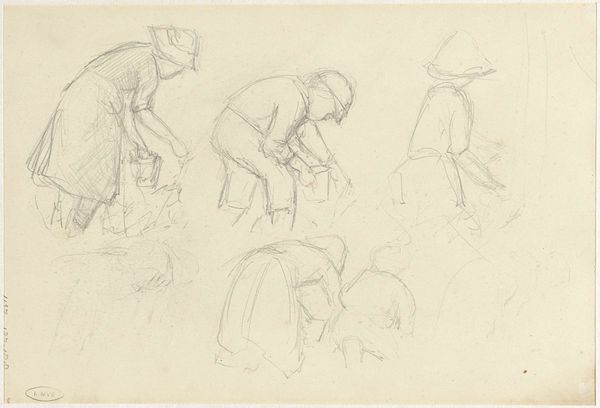

Curator: Right, let's talk about this compelling study by Pieter de Josselin de Jong, dating from 1871 to 1906, called "Studieblad met schetsen van een spittende arbeider." It's a page filled with sketches of a laborer digging, created with pencil and graphite. Editor: It strikes me as an ode to toil, though a somewhat detached one. The repetition gives it an almost scientific feel, like documenting a process rather than celebrating a human being. The different poses and angles offer dynamism to the scene. Curator: Exactly. Academic art of this period often explored the everyday life of the working class, but with an eye for observation. Look at the details—the way he captures the weight and strain in the man's posture, the bend of his back, the set of his jaw, there is beauty to be found in repetitive, demanding labour. You can almost feel it, like observing the motions of Sisyphus but rendered with reverence and respect. Editor: For me it highlights how the representation of labour is often divorced from its reality. The almost rhythmic repetition, like a stop motion of a physical job, abstracts the labour into an aesthetic exercise and it obscures the material reality behind it – the fields being tilled, who owns them, the produce of this hard toil, where is it sold, and who benefits? Curator: That is true, this isn't about the social injustices of the time. De Jong seems most fascinated with the human form in motion and, I imagine, practiced his draftsmanship by observing this man. I see those individual lines almost like strands of fabric or elements of a social class. It has a quality almost like a textile: woven by a machine doing mechanical motions with one man becoming a template or avatar of that industrial process. Editor: I do see that, how the individual forms become a tapestry representing work! But ultimately, even considering those small observations of musculature, you're left with a feeling that this exercise transforms labour, that the action itself becomes just another object, viewed clinically and almost dehumanized. Curator: A fair point, perhaps. I suppose it comes down to how we view labor – as an ennobling activity, or simply a means to an end. Editor: Indeed. It's in these tensions, I think, that we find the most interesting dialogues with art. This piece raises difficult questions for me in my position. What should I be amplifying about material art history? Curator: Well put. These are exactly the type of conversations art should spark and provoke. It certainly provides us all, at least, food for thought.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.