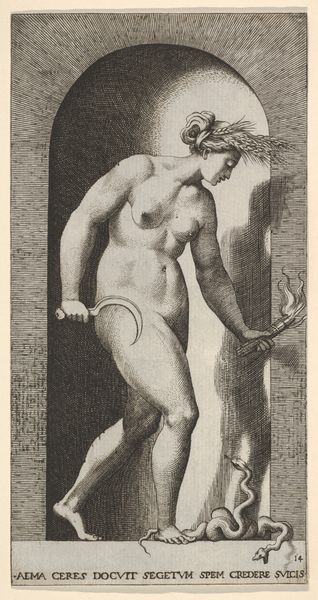

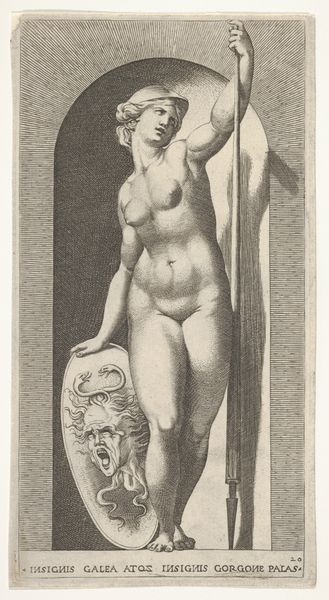

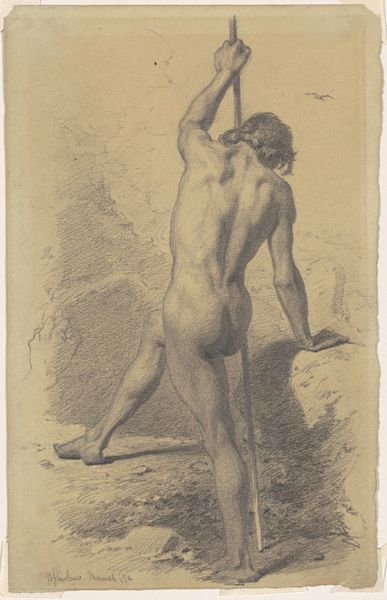

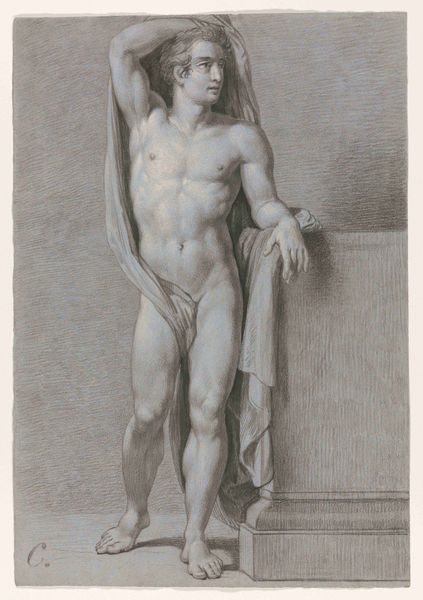

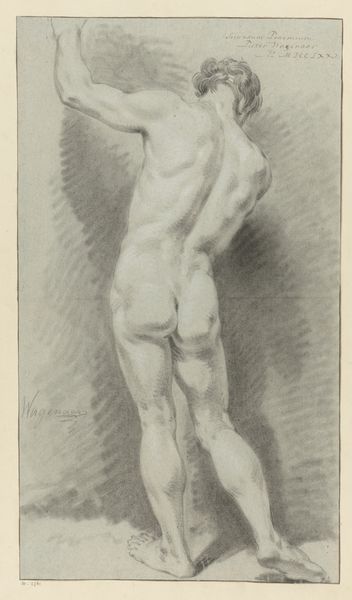

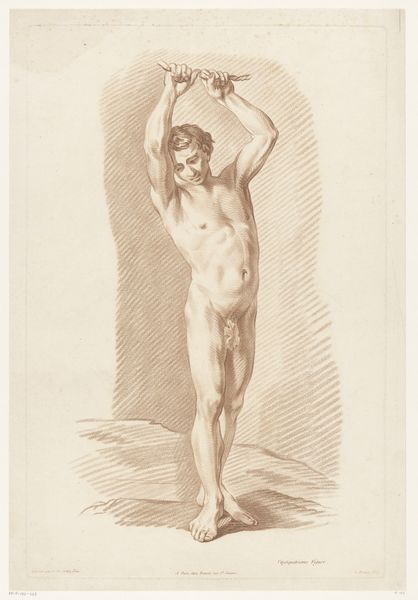

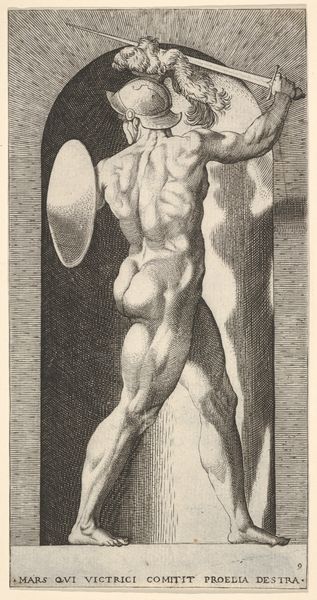

Plate 16: Hebe in a niche with her hands in the air, running to the left while looking to the right, from a series of mythological gods and goddesses 1526

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

# print

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

italian-renaissance

#

nude

#

engraving

Dimensions: Sheet: 8 9/16 × 4 1/2 in. (21.7 × 11.5 cm) Plate: 8 3/8 × 4 5/16 in. (21.3 × 11 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Let’s discuss this engraving by Giovanni Jacopo Caraglio, made in 1526. It's titled "Plate 16: Hebe in a niche with her hands in the air, running to the left while looking to the right, from a series of mythological gods and goddesses." What’s your immediate take on this depiction, Editor? Editor: She seems caught, like she's bursting out of that architectural frame—urgent, maybe escaping something? I see a female figure, nude, seemingly rushing toward something—or fleeing. Curator: Yes, it’s Hebe, the Greek goddess of youth, caught mid-motion. Consider the production process here. Caraglio, a master engraver, translated classical sculpture—likely a bronze or marble—into a graphic print. That act of translation shifts the very nature of the form. He wasn't casting bronze. He was carefully cutting metal, impressing an image onto paper, allowing the reproduction and dissemination of classical forms. Editor: It makes me think about the politics of idealized beauty during the Renaissance. Caraglio’s Hebe seems like an allegory for perpetual youth, which would certainly be relevant considering how much women were commodified at this historical juncture. This image seems to idealize feminine form while stripping it of much individual agency. Curator: Exactly. Look closely at the lines. They’re meticulously rendered, mimicking the contours of a sculpted body. Note also the niche around Hebe—that shape almost imprisons her. This emphasizes the goddess's perfection but does, in some sense, immobilize her. The medium serves a specific end here. Editor: It’s fascinating how you can trace those concerns about artifice and fabrication— the lines almost simulate a classical aesthetic while simultaneously exposing the limits of what an engraving can actually accomplish. How much can you really “liberate” the goddess Hebe with an artistic format such as this one? Curator: Right—engravings could be mass produced and shared widely and, yet, its materiality speaks to very careful acts of manual reproduction. I mean, consider the labor that was involved, carving into the metal, proofing, adjusting. These processes are, in essence, collaborations between human intention, material properties, and practical applications. Editor: It raises intriguing questions around art and production. By paying close attention to engravings, we gain insights into gender, power, beauty and freedom, while we contemplate what the production process truly entails for both maker and muse. Curator: Agreed. This small print contains so much about the processes and cultural dialogues during its making. Editor: A lasting commentary that moves beyond aesthetics.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.