print, etching

#

portrait

#

allegory

#

baroque

#

pen drawing

# print

#

etching

#

figuration

#

vanitas

#

line

#

islamic-art

#

history-painting

#

realism

Dimensions: height 115 mm, width 95 mm, height 77 mm, width 55 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

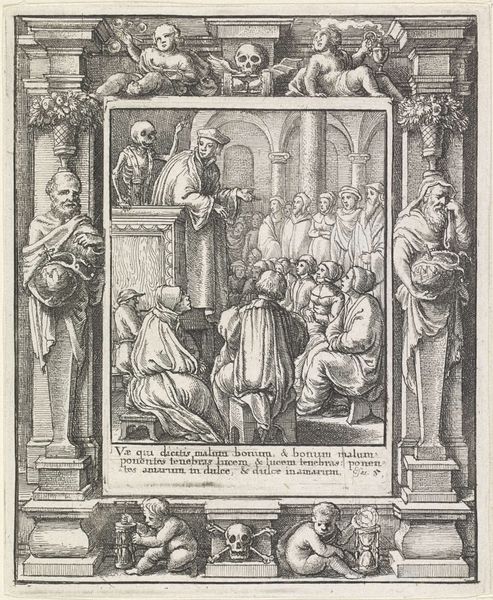

Curator: This is "The Abbess and Death" an etching by Wenceslaus Hollar, dating from 1651. It's quite striking. Editor: It is somber, definitely. The starkness of the etching emphasizes the gravity of the scene. Look at how death is almost leading her into what looks like a building, while her young apprentice is gesturing. Curator: Indeed. The print medium itself plays a vital role in understanding this piece. Etchings like this one, with their relatively low production cost, made such allegorical imagery accessible to a broader public than, say, an oil painting might. Consider who might have bought or distributed prints like these— what workshop produced them and for what purpose? Editor: Right. Prints had a different kind of social life back then. Their impact extended into homes and perhaps inspired different kind of popular, didactic discourse in ways we can't imagine now. The image of Death leading away the Abbess reflects a society grappling with disease and mortality. The Catholic Reformation's focus on penance and mortality must also be taken into consideration. How do you see the inscription tying into all of that? Curator: It’s interesting. “Laudani magis mortuos quam viventes” —praising the dead more than the living. Its material inclusion, the physical act of adding text, solidifies its purpose as more than just aesthetic, almost a functional reminder. The production here wasn’t just about aesthetics; it was about creating and distributing cultural value centered on certain social and spiritual behaviors. Editor: Absolutely. And it would be worthwhile to research how images of Death and dying were regulated, circulated and consumed during this period in places like Prague and elsewhere. Where exactly was this print made, for what audience? It all contributes to our understanding. Curator: Examining its presence in different collections might show its importance for understanding 17th-century Central European artistic culture and its ties to broader social phenomenon such as post-plague reflections on earthly impermanence. Editor: Yes, tracing those historical pathways through both institutional and public spaces gives us greater clarity not just on Hollar's artistry, but the complex interplay of art, religion, and public perception. I keep noticing all of the hourglass figures within the ornamentation—another obvious Vanitas. Curator: Considering both the materiality of the work, and its journey throughout the centuries makes for a potent investigation indeed. Editor: I agree. I find myself moved by how such a small etching opens into such a panoramic view of history and human existence.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.