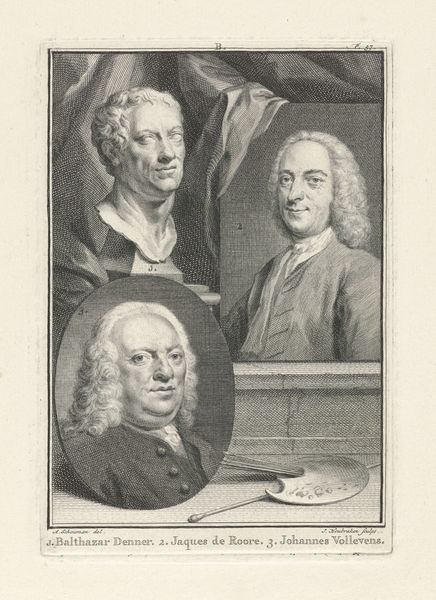

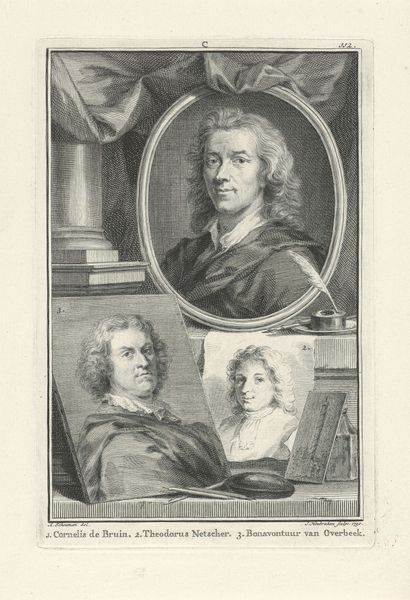

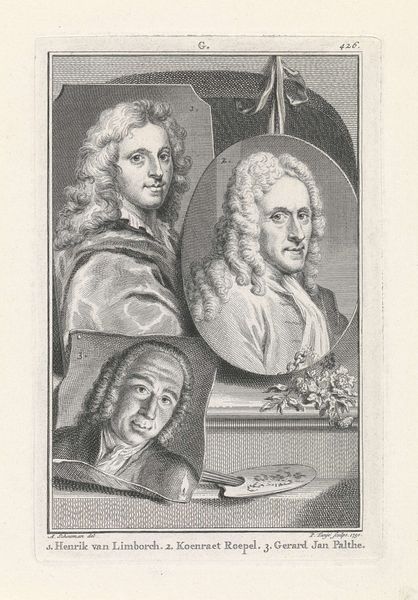

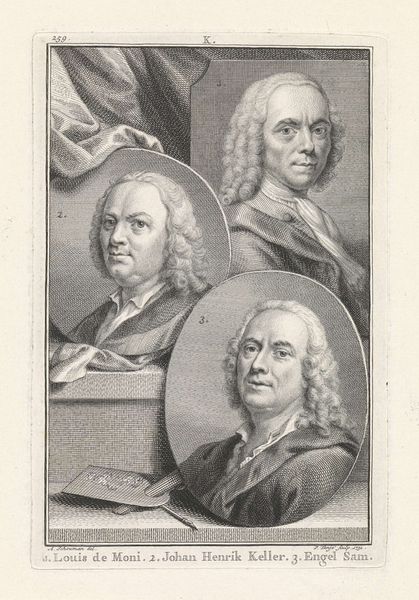

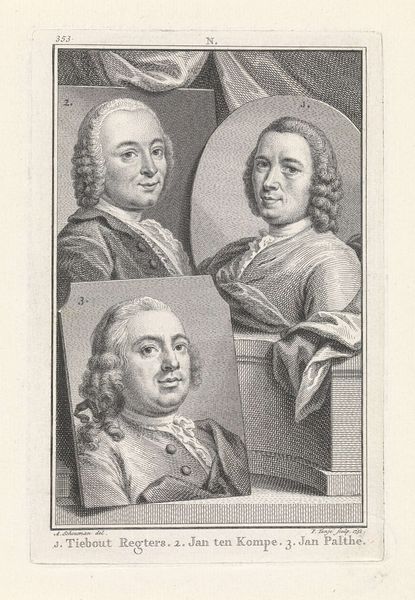

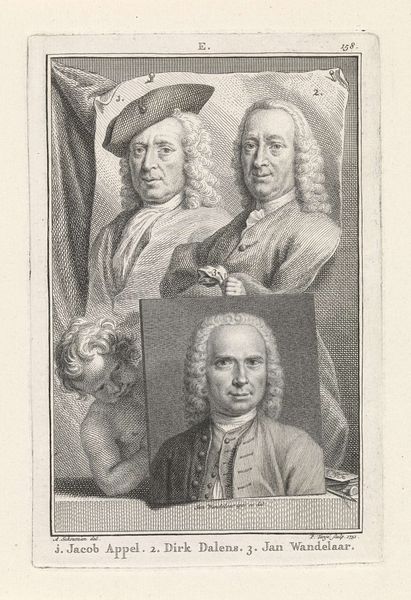

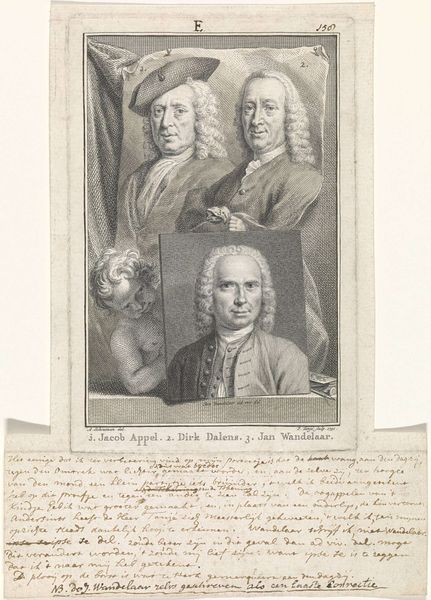

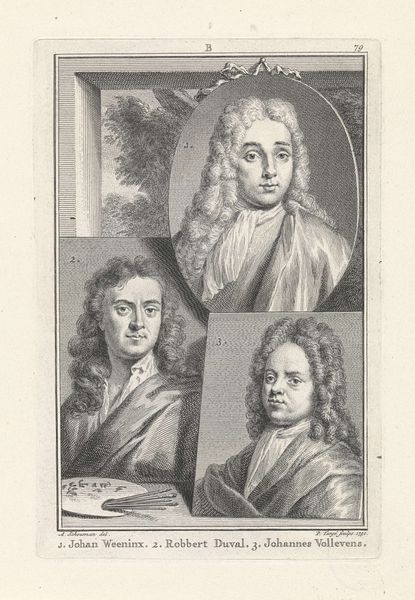

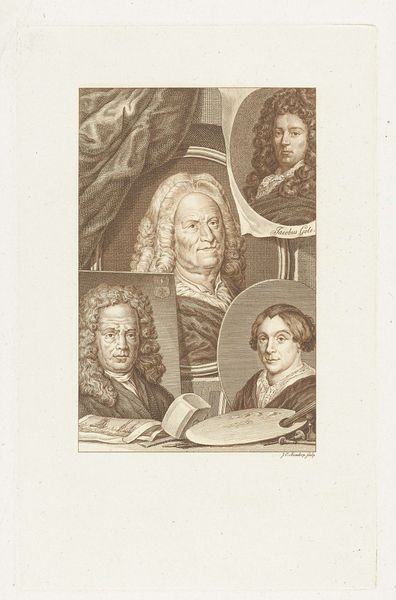

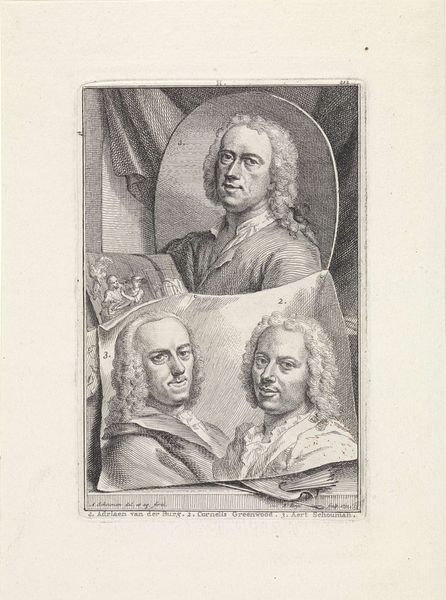

Portretten van Arnold Boonen, Carel Borchaert Voet en Isaac de Moucheron 1750

0:00

0:00

pietertanje

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

traditional media

#

group-portraits

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 158 mm, width 105 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this engraving, "Portretten van Arnold Boonen, Carel Borchaert Voet en Isaac de Moucheron," made around 1750 by Pieter Tanjé and currently residing at the Rijksmuseum, the most immediate thing I notice is the rigidity of its layout. Editor: That's interesting. My first impression is of a certain… stuffiness, even a discomfort emanating from these men. Maybe it's the powdered wigs, but there’s something about their collective gaze that feels a bit unsettling. What kind of social statements are being made through presenting them this way? Curator: Well, beyond personal discomfort, such group portraits during this time served specific social functions. They visualized power structures, artistic communities, and elite networks. This print functions as a kind of eighteenth-century "who's who," and probably served to solidify the social standing of the subjects by literally engraving them into cultural memory. Editor: So, we're not just seeing individual portraits; we're seeing the construction of a cultural elite. It raises questions about who is included, who is excluded, and whose narratives get perpetuated. The decision to include these three, and how they are visually presented, reinforces specific societal values and power dynamics. Curator: Precisely. We also must consider the material and its accessibility. As a print, this image could be reproduced and disseminated, broadening its impact beyond an oil painting commissioned for a private collection. How does the very act of reproducing these images change the way the artwork or the artworkers are understood and valued by Dutch society in 1750? Editor: That act of wider distribution is indeed significant. Who got to see this print and what conversations might it have provoked? I find myself thinking about the role of these individuals beyond the art world and asking, How does the depiction of these men impact our broader understanding of art history in that period? Curator: The Baroque period's aesthetics are not always accessible and equitable. So understanding these complexities—these visual cues, these inclusions, these social gestures—becomes paramount in how we discuss pieces such as these portraits from Pieter Tanjé. Editor: Absolutely. For me, questioning these pieces from an intersectional lens allows us to engage more fully with the artwork in this present moment, recognizing the inherent subjectivity embedded in the portraits from the 1750s, while revealing an even broader narrative for today’s audiences.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.