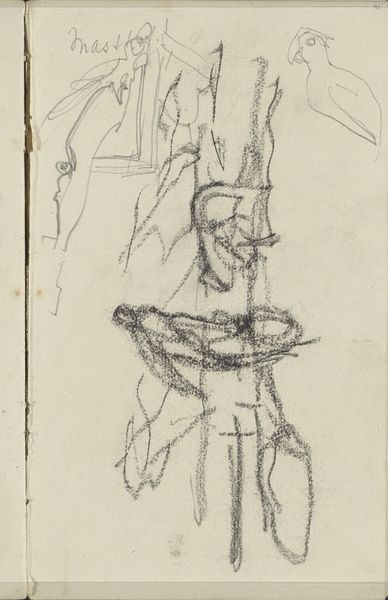

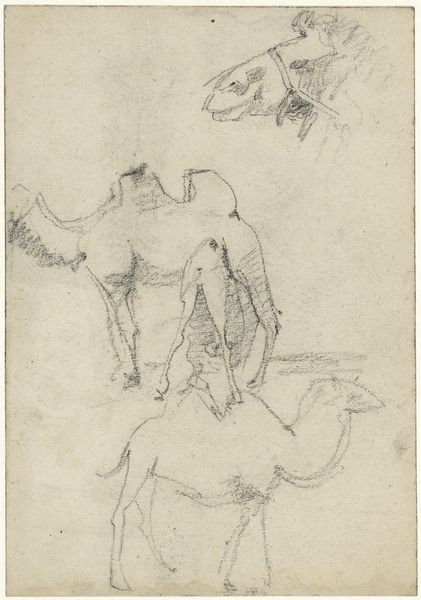

drawing, pencil

#

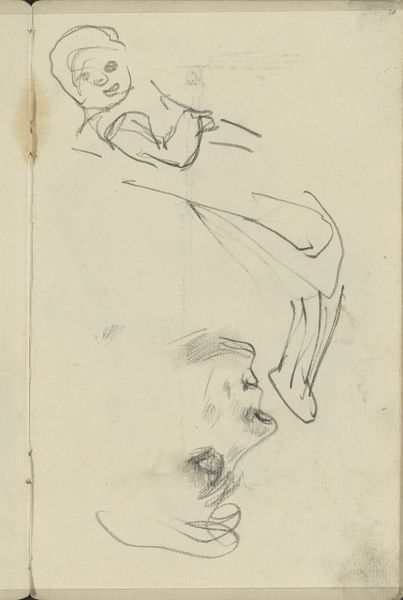

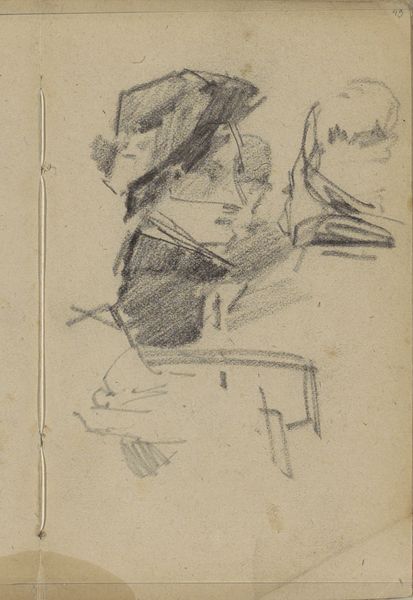

portrait

#

drawing

#

quirky sketch

#

dutch-golden-age

#

impressionism

#

figuration

#

personal sketchbook

#

idea generation sketch

#

sketchwork

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pencil

#

line

#

sketchbook drawing

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

sketchbook art

#

initial sketch

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

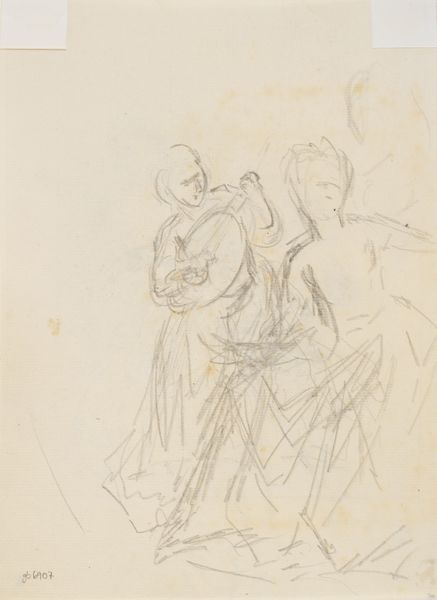

Curator: Here at the Rijksmuseum, we have "Zittende vrouw," a pencil drawing created around 1882 by George Hendrik Breitner. The piece seems to capture a fleeting moment, a woman captured in an intimate and informal setting. Editor: It’s a captivating, but subdued, sketch. The tentative lines and visible erasures convey such immediacy and an exploratory mood, as if the artist were thinking through his observations in real time with no frills or over encumbrances of materials. Curator: Breitner was known for documenting daily life in Amsterdam. I wonder about the woman portrayed, a potential model and her role. Was she of the working class? What would be the broader narrative of female representation during that period of societal change? Editor: The hasty nature of the marks suggest to me that this study comes directly from life: a person observed quickly on a train, perhaps? A domestic helper in the background? The rapid sketch makes it inherently ‘of the people,’ devoid of formal commissions from the bourgeoisie or pretensions of a Royal sitting. Curator: Indeed, his process reflected that modern sensibility of direct experience, influenced by movements like Impressionism. But if we examine art history, there are gaps in understanding—particularly how class, race, and gender intersected with labor during the industrial revolution. Did such works play a part of critiquing structures? Editor: To your point, considering this piece as more than an observation opens up rich territory: what exactly was the paper source for this study, its physical makeup and costs? What specific grade of pencil would Breitner use here to rapidly deploy an aesthetic, or his specific viewpoint of society onto something tangible and reproducible for his patrons? Curator: Looking at such sketches lets us connect these seemingly random acts to their sociohistorical context. The quick, deft strokes may belie greater discussions happening among a collective. In turn, it provides some means of addressing structural omissions prevalent across art historical circles, so we become critical in how value judgments have taken place. Editor: Precisely! By connecting these observations with the materiality and means of artistic labor and production—sketch paper, graphite, distribution of patronage—, it allows us an enriched tangible and nuanced perspective. Curator: It has given me much food for thought! Thank you for taking that brief look with me, Editor. Editor: My pleasure. Let's look into a new one soon!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.