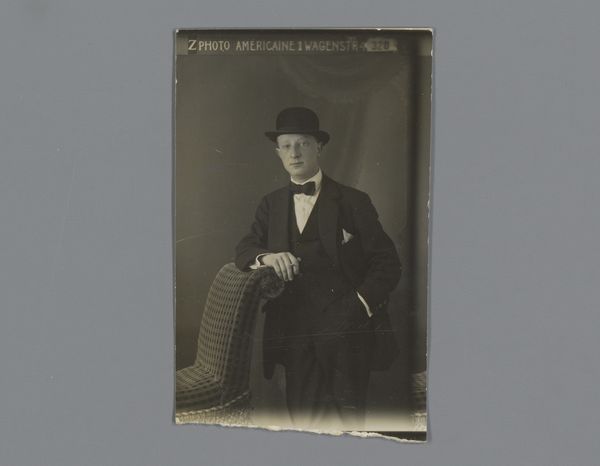

photography

#

portrait

#

photography

#

genre-painting

#

modernism

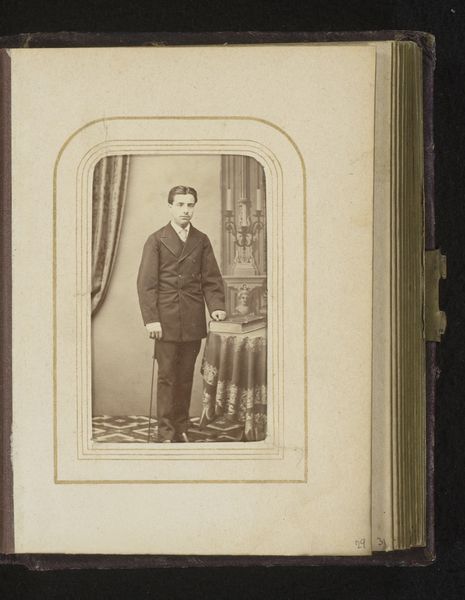

Dimensions: height 84 mm, width 49 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This portrait, attributed to Foto Americaine and titled “Portret van een man, aangeduid als Guilleame,” was likely created between 1912 and 1918. Editor: There's a compelling austerity to it. The sepia tones and the stiff pose convey a sense of formality, almost a melancholy detachment. I'm drawn to the sitter's hand, resting delicately on the patterned chair. Curator: Indeed. And consider the studio itself – Foto Americaine. Understanding the studio's location and clientele gives us a vital insight into the portrait's production. Was this a high-end establishment, catering to the bourgeoisie, or something more accessible? That affects the cost of having a portrait made, and the implied status of the sitter. Editor: Right. And thinking about materiality, it’s a photograph, meaning there’s a mechanical reproducibility inherently built into it, quite unlike painting. How does this affect our interpretation of this man’s desire to be seen and remembered? This photo presents an interesting perspective in our current culture where we're all creating images, but in the past, this may have been an incredibly unique commodity for this man. Curator: Precisely! This era was witnessing photography becoming more commonplace, influencing visual culture profoundly. Portraits once reserved for the elite were gradually democratized. Was "Guilleame" conscious of his representation within a shifting social landscape? Editor: What kind of labour and craft underpinned this? The photographer needed technical skills, equipment, chemicals… then the sitter presumably had to pay for the service, wearing particular clothing that denoted social status. Every element seems carefully curated. The patterned chair even appears very intentionally posed in this frame. Curator: Absolutely, it's all meticulously arranged! Looking closer at the material context opens up considerations about the very politics of imagery. This isn't just a man's face, but a statement about identity, class, and participation in modern society at that specific moment. It’s about visibility and being visible in a controlled and prescribed manner. Editor: So, we see a tension – a carefully constructed representation intersecting with this new potential for photographic democratisation. It forces you to ask, how revolutionary was the impact of photography, and how many elements of traditional hierarchical portraiture survived in this new medium? Curator: Yes, the history here challenges us to consider not just the sitter, but the whole complex web of societal forces, institutional settings and photographic technology which combined to produce this very singular portrait. Editor: The convergence of production, labor, materiality, and class certainly complicates our interpretation beyond just 'a picture of a man.' Curator: Indeed. It encourages a more critical and expansive engagement with the historical significance of photographic portraiture and studio context of early 20th-century imagery.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.