Dimensions: height 41.2 cm, width 30.3 cm, thickness 0.8 cm, depth 5.6 cm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

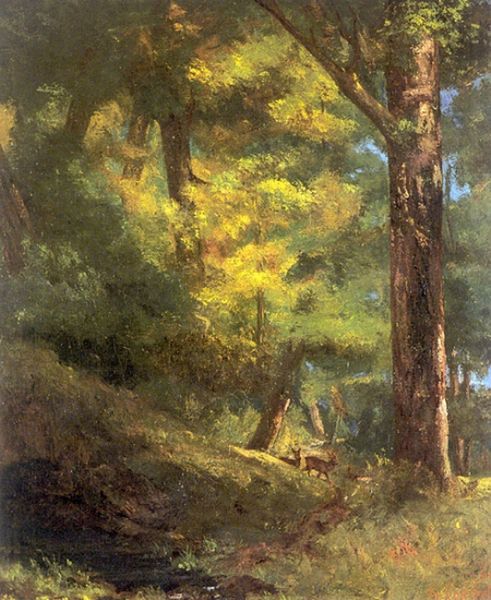

Curator: Immediately, I notice the subtle lighting – it feels very northern European, melancholic. Editor: Indeed. Here we have Johannes Warnardus Bilders' "Bosgezicht bij Wolfheze," created sometime between 1860 and 1890. It's an oil-on-canvas landscape scene currently housed here at the Rijksmuseum. Curator: The application of paint is quite remarkable. It suggests a dedication to "en plein air" painting—I wonder how the shift to tube paints impacted his ability to be out in the landscape versus studio-bound. Were ready-mixed colors more egalitarian in production, allowing more landscape artists to operate outside traditional art systems? Editor: That's an interesting consideration. Looking at the painting through a social lens, one can't help but contemplate the romanticization of nature and its connection to ideas of national identity and perhaps even escapism amidst the increasing industrialization of the Netherlands. Who has access to this "nature"? How is land being commodified and experienced differently based on class and labor at this time? Curator: Well, Bilders did mentor many artists in his home, and he actively critiqued the Hague School style dominant at the time. His dedication to accurately portraying tones led him to unique glazing techniques that are still debated today. This commitment reflects a very active artistic network, concerned with developing a particularly "truthful" way of rendering the Dutch landscape. Editor: Absolutely. Bilders’ meticulous technique is undeniable, but the act of framing and idealizing a scene also holds social significance. Landscape painting can also contribute to the erasure of histories. It can obscure narratives of displacement, labor exploitation, and ecological change that occur on these same lands. Who are present and who is made absent here in Wolfheze, in the late 19th Century? What are the silent, excluded voices? Curator: So you’re challenging us to ask who benefits and suffers when we aestheticize specific landscapes through artistic means. Editor: Precisely. By looking at these pieces as complex reflections of cultural and political tensions, we might more fully address and challenge any assumptions made when faced with the quiet stillness and beauty depicted in his landscape. Curator: That really shifts how I view Bilders’ artistic intention, framing him less as purely an objective recorder and more as a conscious participant in broader conversations. Editor: Hopefully it's reminded us that this evocative work offers, not just visual delight, but critical opportunity to engage in complex discussions about place and power.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.