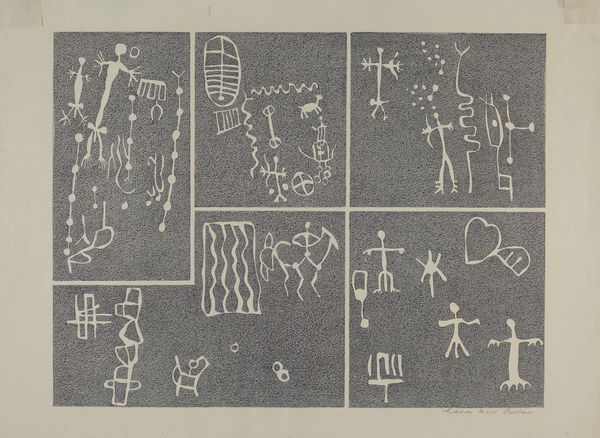

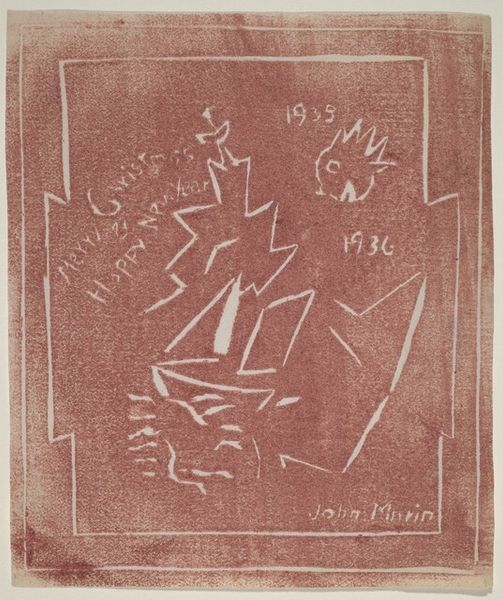

graphic-art, print, paper, woodcut

#

graphic-art

# print

#

figuration

#

paper

#

woodcut

Dimensions: Overall: 36.7 x 28 cm (14 7/16 x 11 in.) overall: 46 x 37.1 cm (18 1/8 x 14 5/8 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

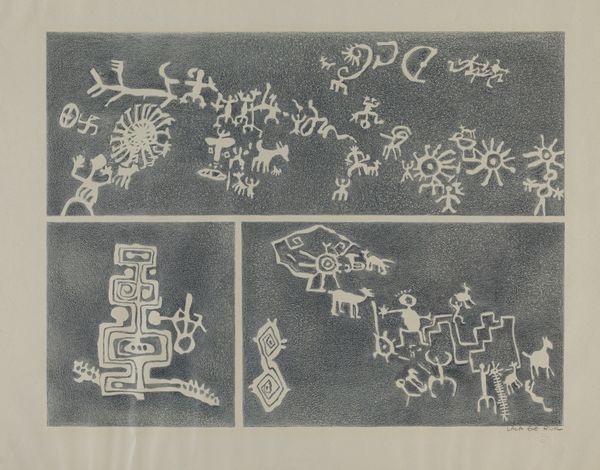

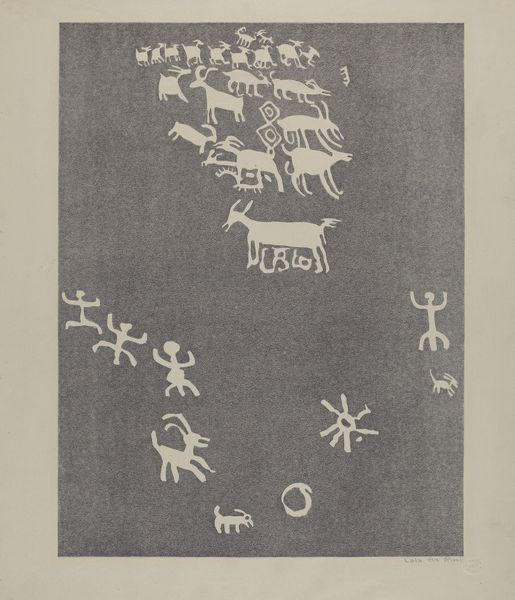

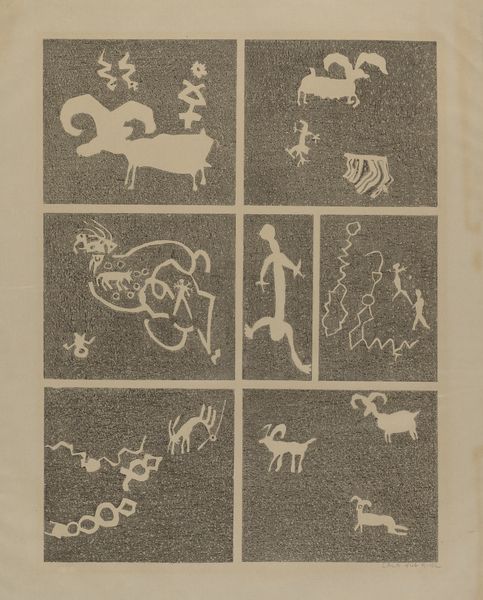

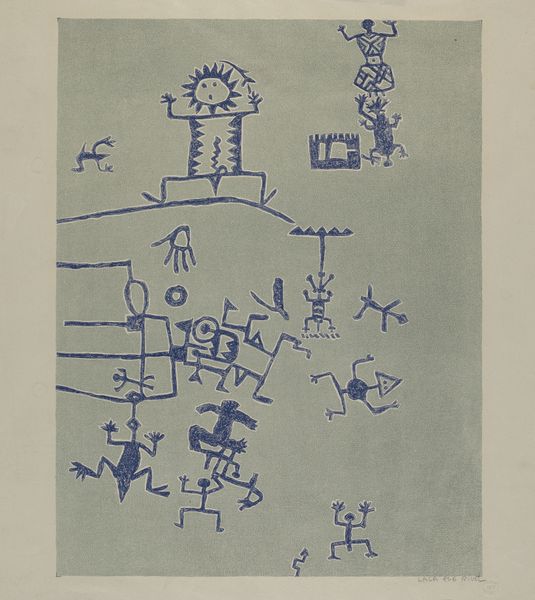

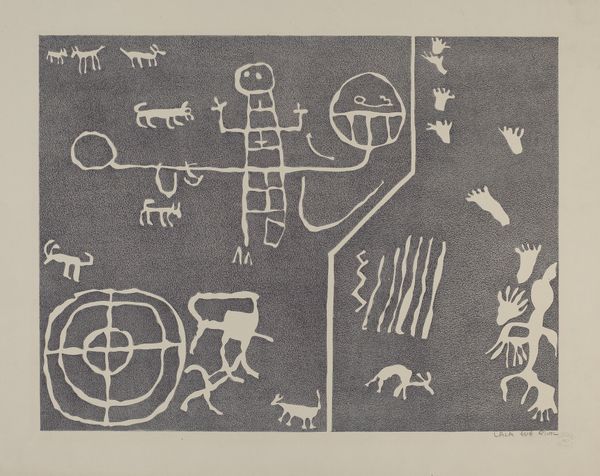

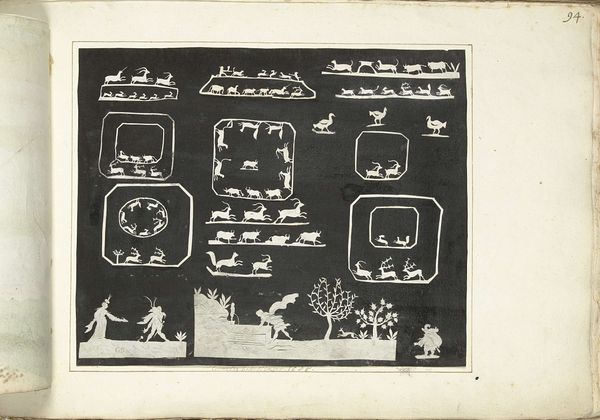

Curator: Alright, let's spend a little time with Lala Eve Rivol’s "Petroglyph", likely created sometime between 1935 and 1942. It's presented as a print, with the linework a ghostly white against a blue-grey ground. First impressions? Editor: Immediately, I’m drawn to its sense of layering—almost like archaeological strata exposed. The animals, the symbols… they speak of ritual and perhaps some kind of mapping exercise? Like finding a hidden language in plain sight. Curator: Yes, the layering is crucial. Considering Rivol’s printmaking process, it mimics the act of uncovering history, revealing images seemingly etched over time. And the visual language does evoke ritual—possibly depictions of hunting scenes, cosmology, maybe even records of seasonal migrations? These markings point to ways of relating to, and recording, land use over vast expanses of time. Editor: Given that these are presented as prints, and thus were designed for reproduction and dissemination, how does the transition from unique rock carvings to a commercially produced print form change the status of the "petroglyph" and its cultural value? And the blue ground is interesting—a kind of ersatz sky or sea perhaps? It looks so synthetic. Curator: That tension between the ancient markings and the mass-produced print is really what gets me thinking. I mean, we're dealing with a simulacrum—a representation of a representation. On the one hand, you’re amplifying ancient stories and sharing knowledge with a wider audience, while also losing something incredibly precious: the direct link to the land. I wonder, does its availability dilute its power? Or is Rivol democratizing access to Indigenous knowledge? I lean towards both/and. Editor: I wonder too if Rivol herself engaged with or collaborated directly with the communities whose visual languages she employed, and if so, what that looked like. This approach could bring indigenous making to a broader contemporary audience while perhaps exploiting the narratives themselves. Also the very clear demarcation by horizontal lines into distinct registers also suggest it's being made 'legible' by a kind of modern western way of looking. Curator: Exactly. And as a reflection, this piece offers us insight into how we grapple with interpreting symbols and understanding narratives from different cultures and temporalities—to look beyond surface appearances. I think "Petroglyph" reminds us of the responsibility that comes with interpreting fragments of the past. Editor: Absolutely. By highlighting the layers of creation and interpretation—the artist’s hand, the historical record, the act of replication—Rivol forces us to confront the ethics of cultural representation itself, its limitations, its transformative possibilities and power dynamics. It's not just *what* is depicted, but *how* and *why*.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.