Copyright: Public domain

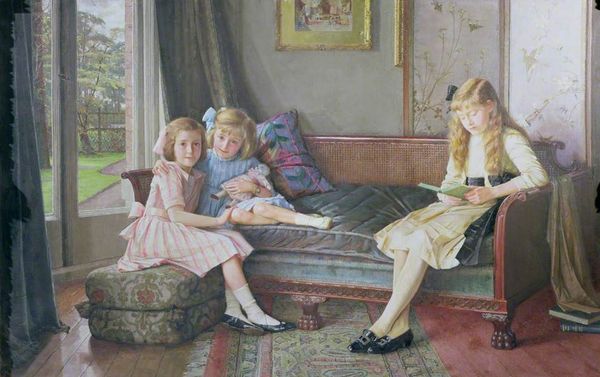

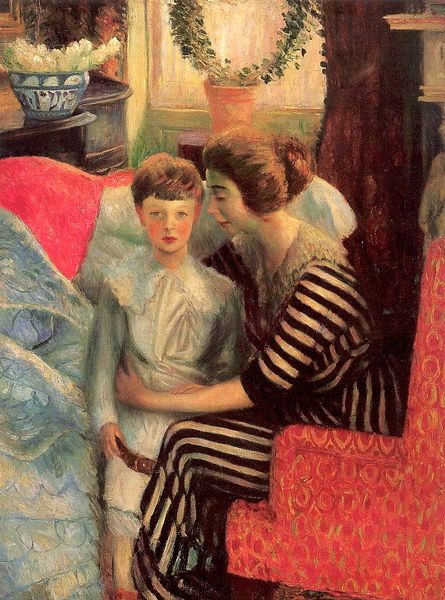

Editor: Here we have Theo van Rysselberghe’s "Three Children in Blue" from 1901, created with oil paint. It strikes me as a very formal, almost stiff portrait despite the impressionistic style. What do you make of this piece? Curator: It's tempting to simply read it as a charming portrait, isn't it? But as a Materialist, I see something more profound embedded in the very fabric of this painting. Look at the facture, the repetitive dabs of paint, a near-mechanical application. How does that process, that labor, connect to the subjects themselves? Editor: Well, the dresses are quite elaborate, suggesting a certain level of wealth, perhaps? Curator: Exactly. And the Pointillist technique, popularized by Seurat and others, wasn’t just a style, it was a means of production. Think of the meticulous work that went into crafting those garments. This level of detail speaks volumes about the means of production of both art and the clothes represented within it, and their implied consumption and place in the social structure. Is the artist subtly critiquing this opulence, this consumption? Or is he complicit in its glorification? What are your thoughts? Editor: That’s a perspective I hadn’t considered. It challenges the initial, purely aesthetic appreciation. Curator: Precisely! And consider the blue. It’s not a naturalistic color for skin, so it invites speculation. The artificiality of the dresses, rendered in painstaking detail using an artificial approach, mirrors, and potentially questions, the manufactured nature of social identity. Editor: I see your point. It’s much more than just pretty dresses. The materials, the making – it’s all intertwined with the social context. It makes me think about how different artistic choices influence perceptions of value. Curator: Exactly, you see, material and method directly contribute meaning and provoke discussion!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.