Copyright: Public domain

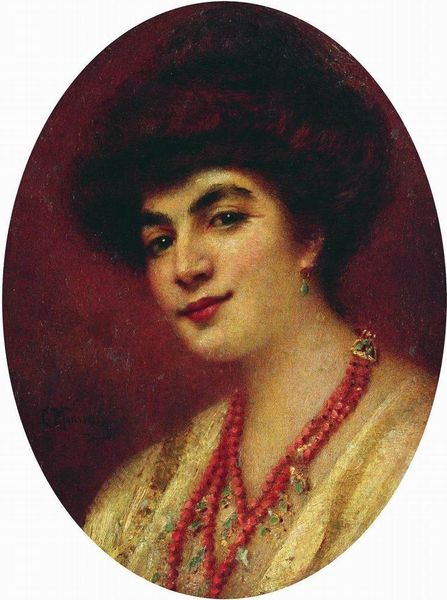

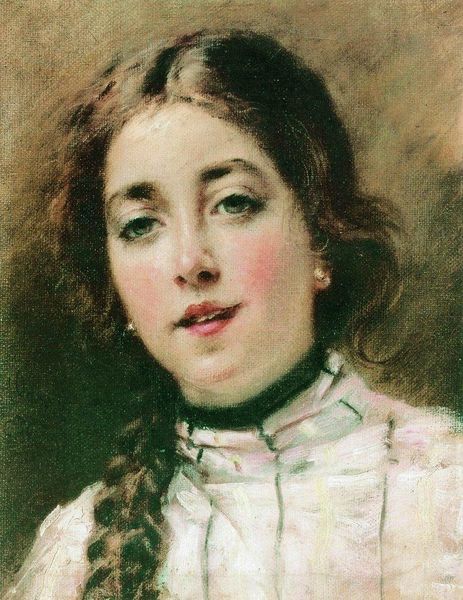

Editor: This is Fyodor Bronnikov’s "Portrait of an Italian Ballerina Virginia Zucchi," created in 1889, using oil paints. It’s interesting how the bright pink dress contrasts with the olive background. What do you see in this piece? Curator: I see a window into the commodification of performance. The oil paint itself, carefully applied, creates a product, a sellable image. The labor Bronnikov put into capturing Zucchi is transformed into monetary value, wouldn't you agree? Editor: That’s a different way to think about it! I was focusing more on the artistry of the portrait. Curator: But isn’t the artistry itself a form of labor? The very choice of oil paint speaks volumes – a durable, historically valued material designed for longevity and, therefore, increased worth. Also, note how the necklace on the ballerina, probably worth more than her outfit! How much work, likely artisanal in nature, had to be completed to create those elements featured in the portrait? What do you think? Editor: So you are saying the value of the painting isn't just Bronnikov's skill but also the physical materials, including labor to extract or build it, needed to make the artwork, the support system around it that gave it cultural value. Curator: Precisely. Bronnikov’s labor interacts with and enhances the value of other laborers as well. In many ways, the very existence of art hinges on materiality and labor. Editor: I hadn't considered that before. Looking at it now, I see how much the material choices and their origins really influence the value and meaning we give to the portrait. It also challenges the myth of the isolated artistic genius. Curator: Indeed, art is enmeshed in networks of material production and social relations. Think of the artist as merely the final contributor!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.