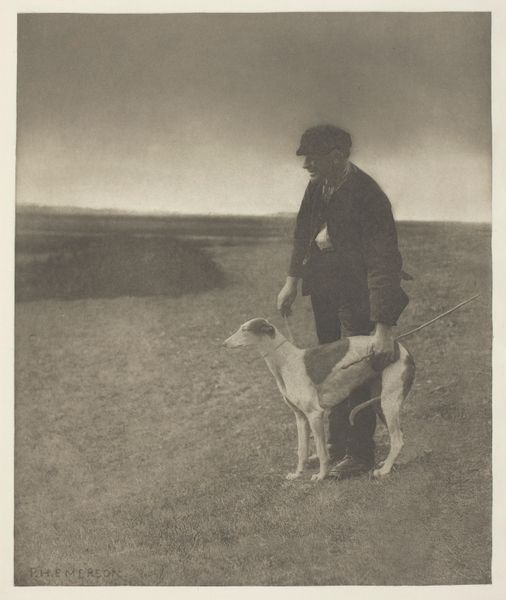

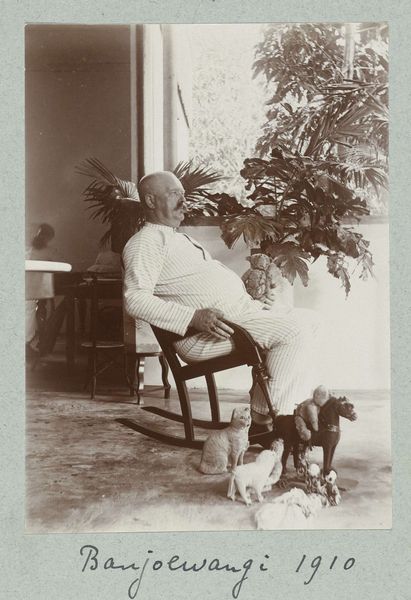

Jachtopziener Frans Stark met zijn hond Nemo in de Muyduinen op Texel c. 1900 - 1930

0:00

0:00

richardtepe

Rijksmuseum

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

print photography

#

dog

#

landscape

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

outdoor activity

#

genre-painting

#

naturalism

Dimensions: height 169 mm, width 225 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Richard Tepe’s “Jachtopziener Frans Stark met zijn hond Nemo in de Muyduinen op Texel,” a gelatin silver print, likely from sometime between 1900 and 1930. Editor: The overall effect is strikingly still, almost solemn. Stark's gaze is intense, the dog relaxed but alert—there’s a clear bond here. The monochrome tones create a lovely nostalgic feel. Curator: The gelatin silver process was pivotal. Its development allowed for mass production, bringing photography to a broader audience. Consider Tepe’s studio and the local clientele; this image provided both service and social representation, right? It captures the work and place within a larger system of production, not simply documenting a man and his dog, but showing a local authority on Texel. Editor: I agree—seeing beyond a sentimental portrait is key. Let's consider the sitter and his social standing. As a "jachtopziener," or game warden, Stark was charged with maintaining local ecological governance and social order. Curator: It’s interesting to think about the labour connected to his role. How the materials for both the print and the sitter’s garb were manufactured and accessed, particularly when considering naturalism as a developing style. What’s reflected in Stark’s attire connects to the place, emphasizing the man’s relationship to this environment, in terms of local or even national identities, you might say. Editor: Right, and by extension, this representation of work—man and dog as collaborators within a controlled rural landscape—needs interrogation. Were all members of this community afforded similar representation or social standing? Who gains and who loses through naturalized power structures on Texel at this moment in time? Curator: Those questions really help us dive deeper into understanding the power dynamics represented, prompting one to explore archives to know whose perspectives have been sidelined to create this particular story. Editor: Absolutely. I’m left thinking about the layers of meaning a seemingly simple portrait can hold when we actively look at it intersectionally, socially. Curator: It's an insightful and rewarding reminder to consider art’s function within systems of exchange. Editor: Agreed; every image is also an artifact of the processes used to create it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.