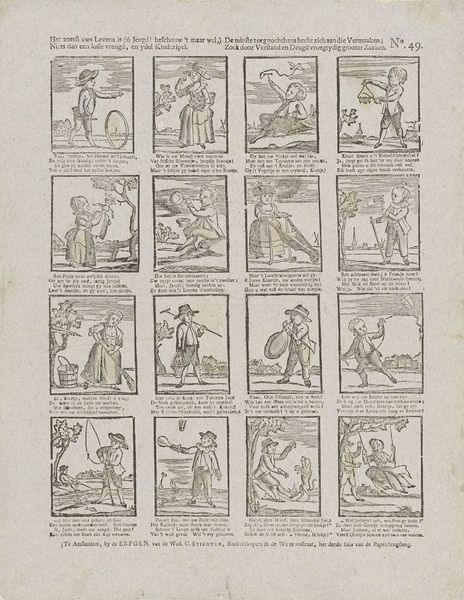

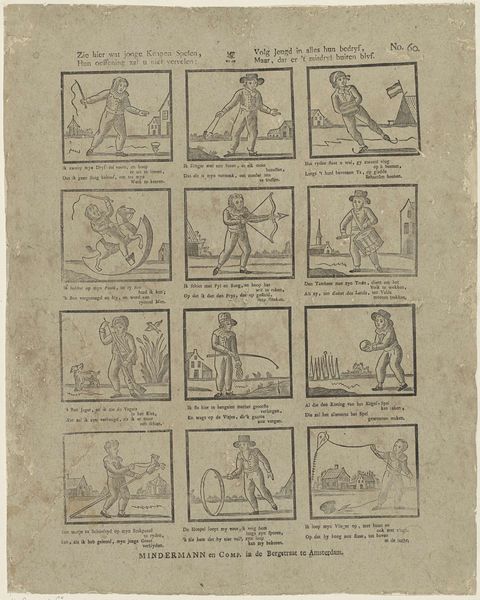

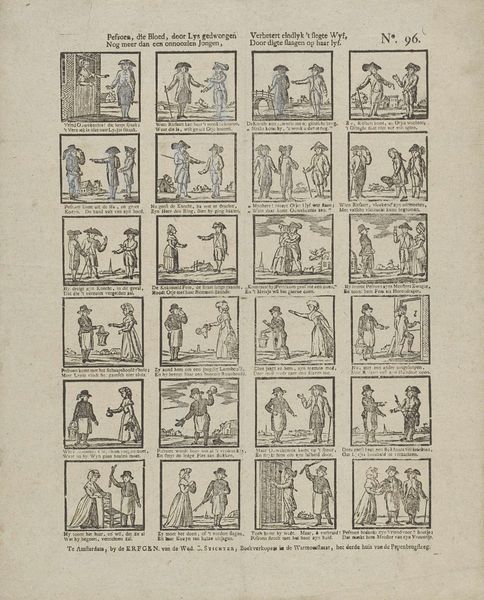

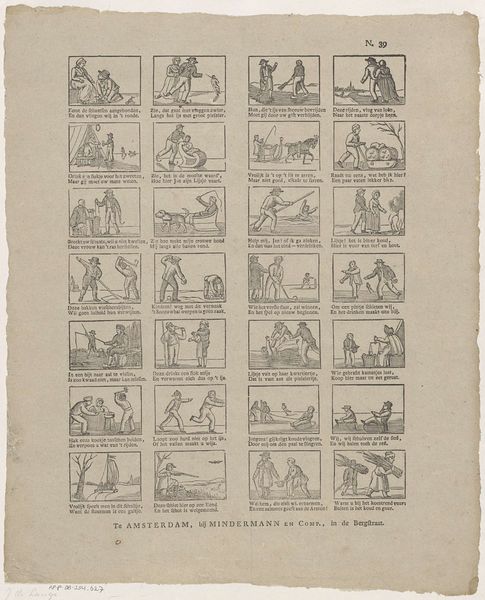

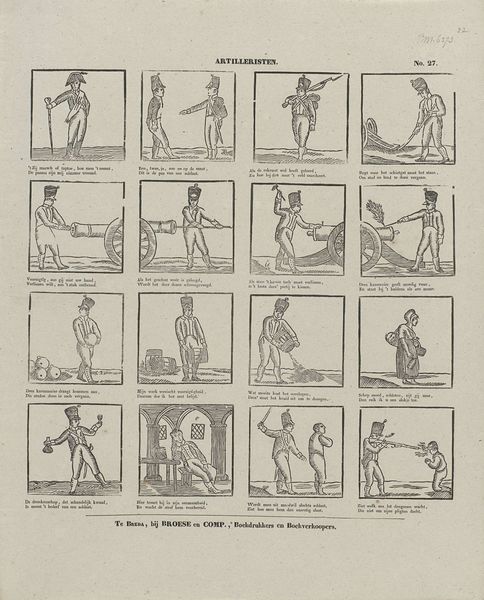

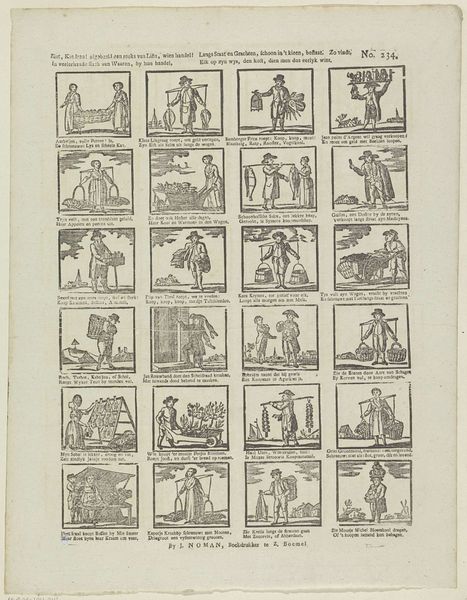

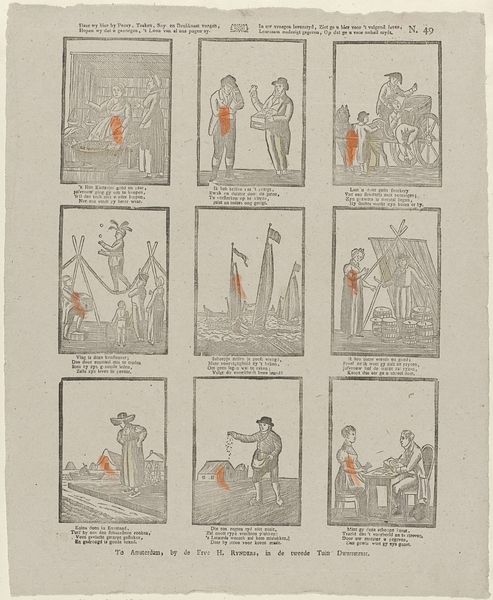

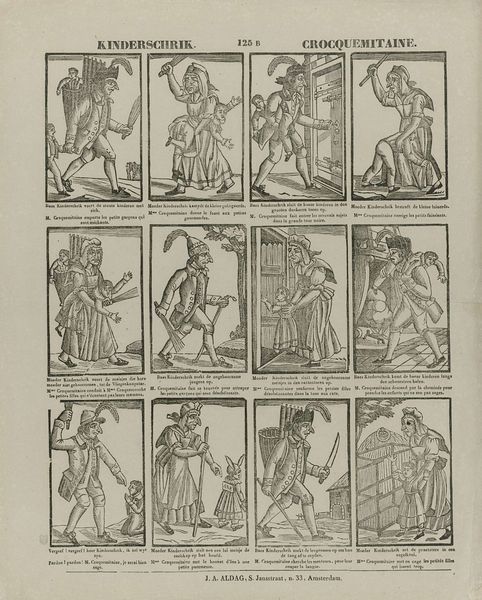

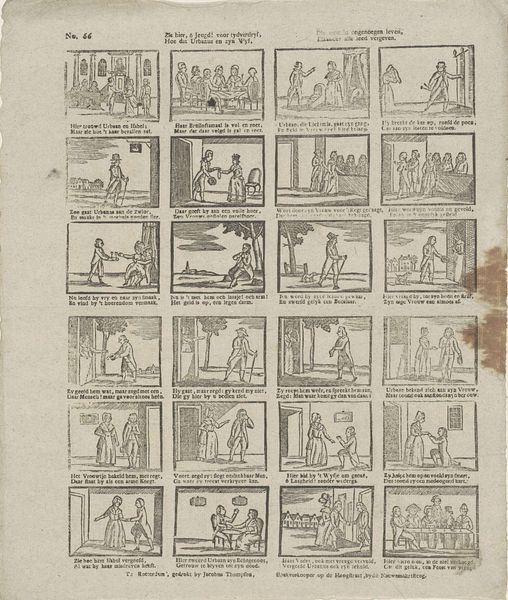

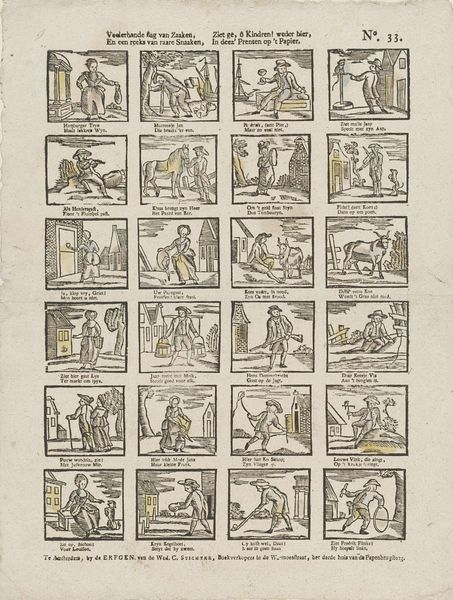

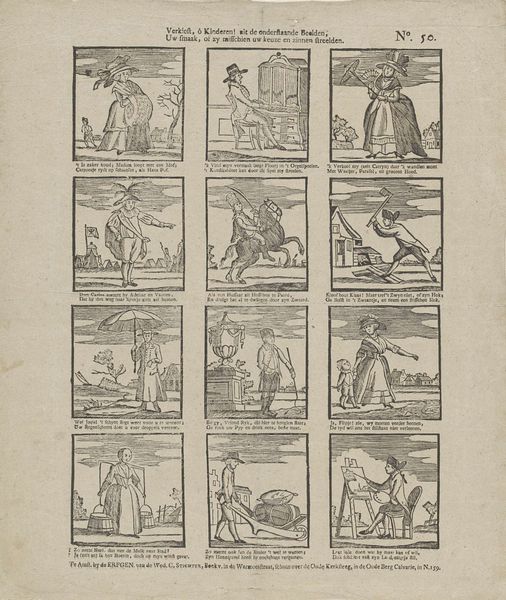

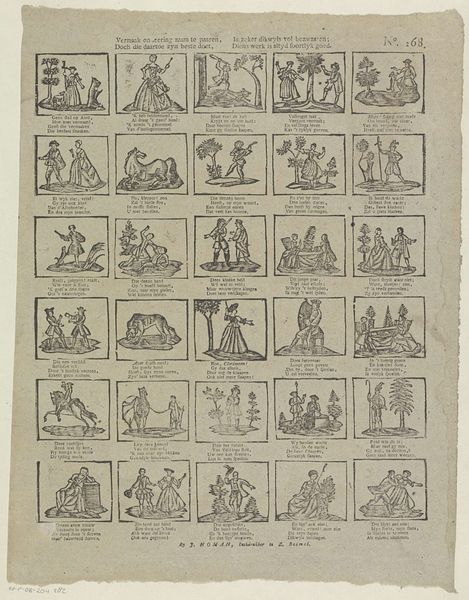

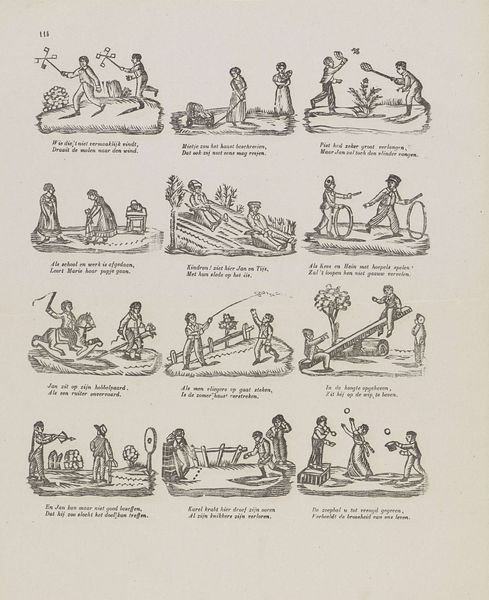

Zie hier tot uw vermaak, waarmeê gij al kunt spelen, / Op dat geen ogenblik, o jeugd! u moog' vervelen 1828 - 1849

0:00

0:00

ervewijsmuller

Rijksmuseum

drawing, print, paper, ink, engraving

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

old engraving style

#

bird

#

figuration

#

paper

#

ink

#

folk-art

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 410 mm, width 331 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This delightful engraving, dating from 1828 to 1849, is titled "Zie hier tot uw vermaak, waarmee gij al kunt spelen, / Op dat geen ogenblik, o jeugd! u moog' vervelen," and it comes to us from Erve Wijsmuller. Editor: What a curious and compelling piece! There's an innocence radiating from it. It feels so deeply rooted in childhood pastimes. The presentation almost feels like a set of postage stamps! Curator: I see it similarly. These are definitely illustrations created from etching or engraving, printed on paper with ink, offering glimpses into 19th-century childhood amusements. Each image, a miniature narrative, invites us to consider the cultural value placed on play and leisure at the time. It feels pedagogical. Editor: Indeed! Note the recurring figures. Are these meant to symbolize types? The diligent worker, the daydreaming child, the aging caretaker? Each possesses familiar attire, suggesting specific roles. Look closer and you might recognize certain characters that reflect an idyllic domestic space. What can you tell us about that recurring visual trope of a bird on a branch? Curator: Considering its origins within the print shop of Erve Wijsmuller, the mass production aspect cannot be understated. These engravings, likely intended for children’s books or educational materials, suggest an interesting tension between artistic expression and industrialized creation. The relatively crude drawing only adds to that suggestion, even its possible consumption as folk art. It's fascinating how the very act of reproducing and distributing such imagery shapes our understanding of childhood in that era. Editor: Absolutely, and this almost lends the illustrations symbolic weight. The simple act of a child with flowers becomes an icon of youthful curiosity, the toy horse transforms into a representation of imagination taking flight. We cannot ignore how folk art uses repetition, of symbols and forms to connect past, present, and future to reinforce cultural narratives that go beyond pretty images. It creates meaning. Curator: It really does offer insight into the lives, labor, and cultural priorities of its era. Editor: I quite agree! By examining its components of craft, reproduction, iconography, and societal function, we reveal this print's richer historical narrative, both materially and culturally.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.