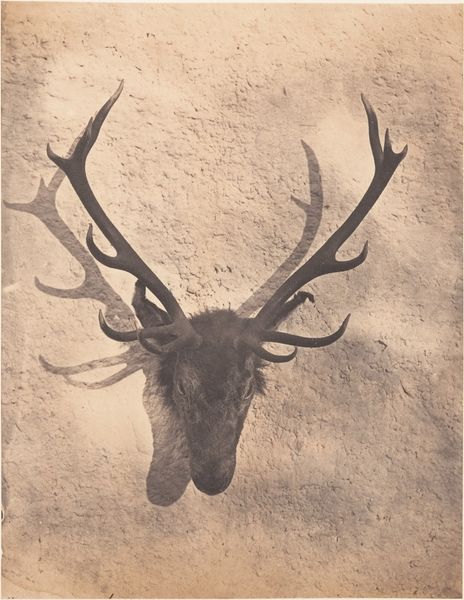

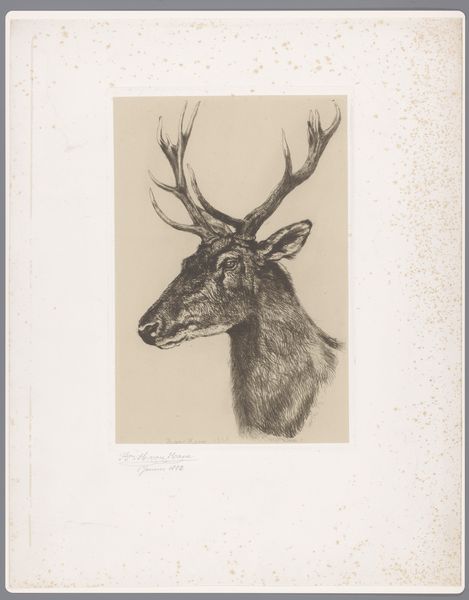

![[Stag Trophy Head, Killed by Ned Ross] by Horatio Ross](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzLzExZjIwNjBlLWI5ZDAtNDU5MS1iNGJkLWUxMjIxZTE0YmVkMC8xMWYyMDYwZS1iOWQwLTQ1OTEtYjRiZC1lMTIyMWUxNGJlZDBfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

print, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

# print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

Dimensions: 17.9 x 14.9 cm (7 1/16 x 5 7/8 in.), corners trimmed diagonally

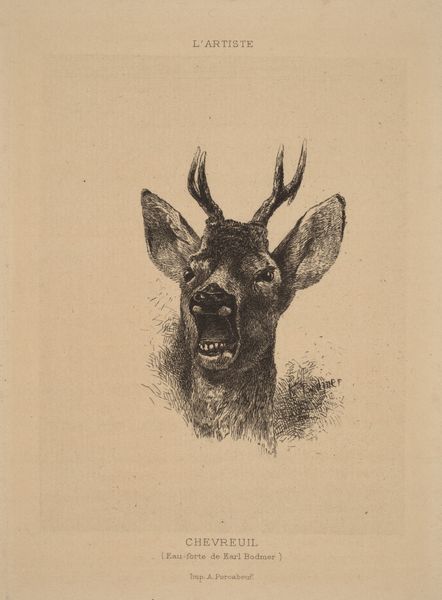

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: So, this is [Stag Trophy Head, Killed by Ned Ross], a gelatin-silver print from 1858 by Horatio Ross. The image of the stag’s skull feels surprisingly stark, even haunting, despite the sepia tones. What do you see in this piece, given its age? Curator: I see a potent symbol of Victorian-era masculinity intertwined with colonial hunting culture. Consider the trophy itself, a monument to domination over the natural world, particularly the Highlands of Scotland, during a period of intense social stratification and land enclosure. What does it mean to “kill” and then display nature in this manner? Editor: I guess it’s a power statement? Ross showing off his skill? Curator: Exactly. Ross, who was part of the privileged class, participated in hunting, thus performing and solidifying his elite status. But let's not forget the historical backdrop; this was taken when Scotland experienced massive changes, including clearances which displaced local communities from their lands, often for deer stalking estates for wealthy landowners. Editor: So you’re saying the stag head isn’t just about hunting; it also hints at social injustice? Curator: Precisely! The "sport" celebrated here contrasts starkly with the dispossession of many Highlanders. We could also explore the link between this display of ‘mastery’ and prevalent Victorian ideals about control and subjugation – the animal kingdom, colonial subjects, even women. Does photographing the trophy change or reinforce these ideas? Editor: It definitely makes you think about who gets to control the narrative, who’s in the photograph, and who's left out. Thanks! I hadn't thought about it that way. Curator: My pleasure! It’s essential to contextualize these objects; only then can we engage in truly critical art history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.