aged paper

toned paper

light pencil work

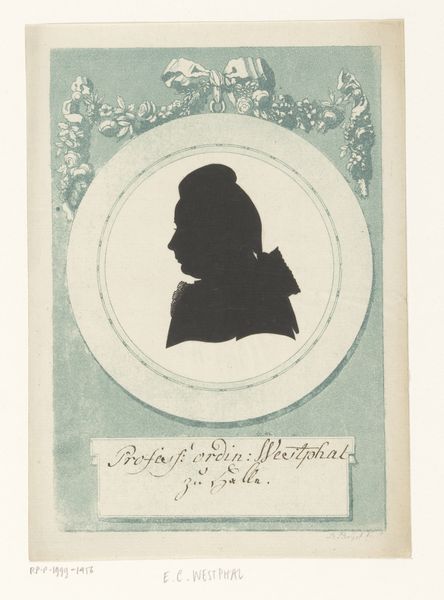

pale palette

parchment

light coloured

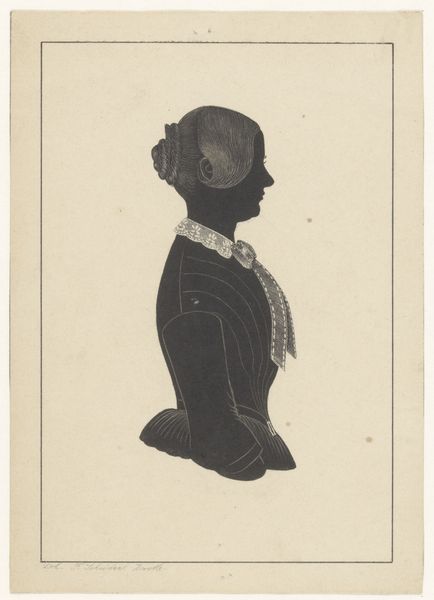

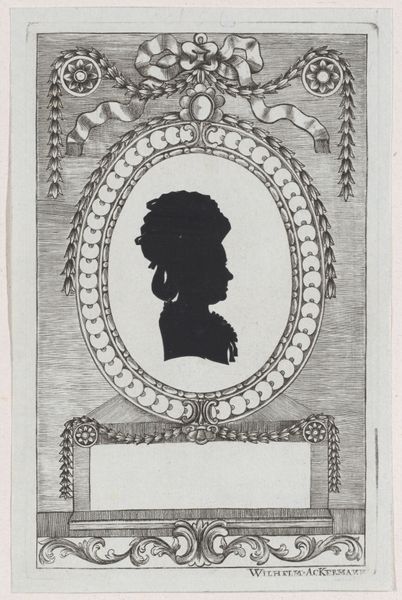

old engraving style

wood background

golden font

vignette lighting

Dimensions: height 181 mm, width 119 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This silhouette portrait of Johann Kaspar Lavater, dating from sometime between 1760 and 1799, is really striking in its simplicity. The crisp black figure against the lightly etched background makes it feel both formal and delicate. What historical factors do you see influencing the creation and reception of a work like this? Curator: It's important to consider the context. Silhouette portraits like these became popular precisely because they were affordable and reproducible, allowing for a wider distribution of images of prominent figures. Lavater, himself, was a hugely influential figure, known for his work in physiognomy - that is, the idea that one's character could be discerned from their facial features. So the production and widespread consumption of this image speaks to a fascination with Lavater's theories, and how art like this engaged in shaping public perception of individuals and promoting the study of these figures, making "knowledge" accessible through imagery. Do you think that the choice of the silhouette as a medium impacted how his ideas were received? Editor: That's fascinating! I hadn't thought about the link between the easy accessibility of silhouettes and the democratisation of knowledge, even pseudoscientific knowledge, like physiognomy. It’s interesting how such a simple image could play a role in shaping intellectual trends of the time. It almost feels like a very early form of mass media. Curator: Precisely! The silhouette, though seemingly simple, held a specific social and cultural weight. The use of reproducible image and their consumption reveal larger forces about cultural identity. By displaying figures within portraiture we can analyze the relationship to its impact and to the viewer, considering what such images tell us about how individuals saw and presented themselves. This informs a more complete portrait of the culture within the frame as well. It’s important to look not only *at* the image but through it! Editor: That gives me a lot to consider – seeing beyond just the face to the forces shaping the world around it. Thanks for that perspective!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.