Dimensions: height 602 mm, width 442 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

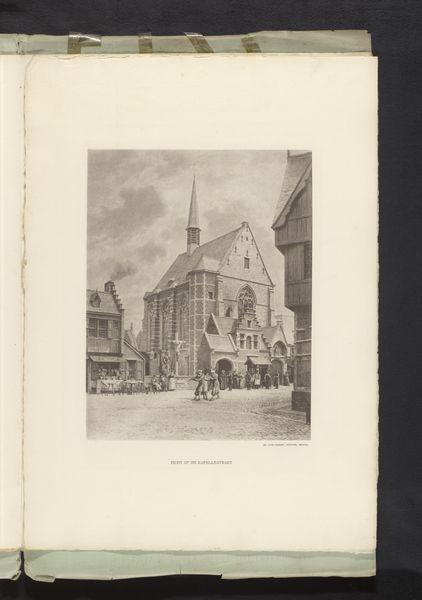

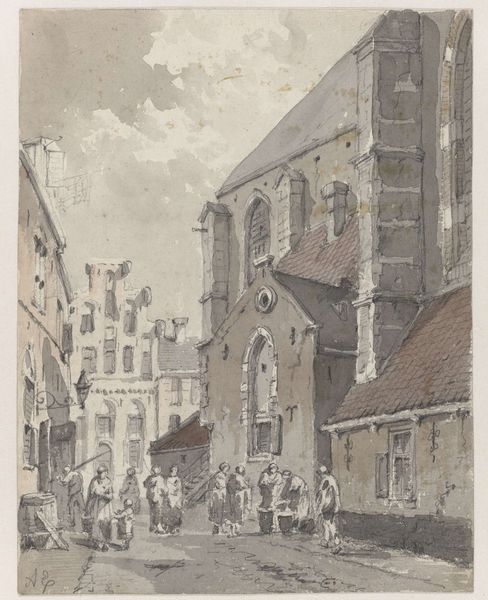

Curator: It possesses a quiet reverence, doesn’t it? There's a sense of solemnity, but also of community, gathered outside the church. Editor: Indeed. We're looking at Alexander Schaepkens' rendering of "Gezicht op de Sint-Maartenkerk in Sint-Truiden," created sometime between 1830 and 1899. The Rijksmuseum houses this cityscape, executed with watercolor and colored pencil, wouldn’t you say? Curator: Absolutely. The soft washes of color give it an ethereal quality, like a memory fading into time. The church spire piercing the sky is such a classic Romantic symbol, pointing towards transcendence. But I am wondering about the social context and about why the image maker was intent on reproducing the image this way... Editor: A crucial question. Consider how the Romantic movement itself emerged amidst the tumult of industrialization and urbanization. These cityscape paintings, particularly of churches, functioned almost as nostalgic yearnings for an imagined pre-modern past. Curator: I agree. I think the very style reflects this impulse— watercolor offers a gentler, less assertive form compared to the rise of photography, which might have looked overly technical to many who enjoyed similar pictures, not only artists. I notice the repetition of the vertical lines—the spire, the building facades, the figures standing tall in procession – like visual echoes. Is it some appeal to tradition or is there something more that strikes your interest? Editor: I can consider the growth of historical societies, art preservation movements and changing audiences as elements to add to the social history you describe here. The colored pencil additions help give texture, a sense of the buildings weathered over time, reinforcing that historical connection to the urban past, so that, through those repeated elements and those media, the viewer relates to it viscerally. And churches—powerful symbols of civic stability during turbulent eras of societal transformation. The building itself acts as a container, guarding a collective memory. Curator: Beautifully put! A testament to the enduring power of place and the art that captures it. Editor: Yes, how it reflects an idealized image in response to societal change, not necessarily objective historical realities. Something for visitors to keep in mind.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.