tempera, painting

#

narrative-art

#

tempera

#

painting

#

figuration

#

costume

#

russian-avant-garde

Copyright: Public domain

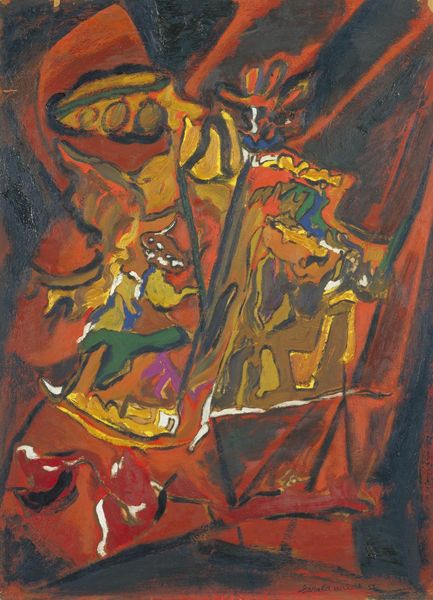

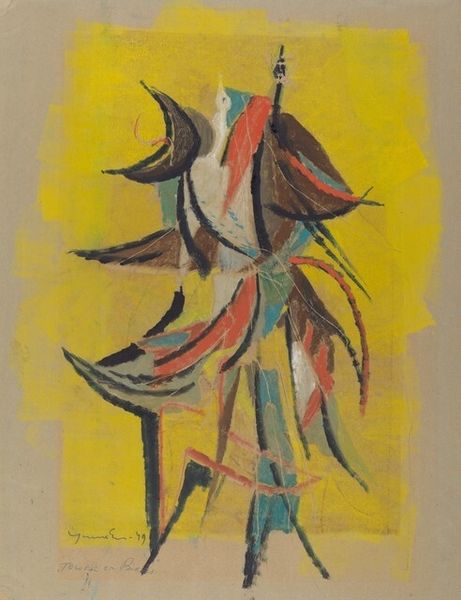

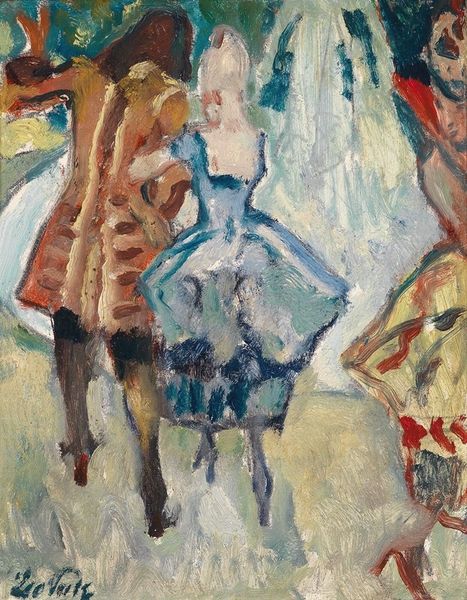

Editor: So here we have Nicholas Roerich’s “Costume design for "Tale of Tsar Saltan"” from 1919. It looks like it’s tempera on…something, maybe board? The figure’s really striking, but what really gets me is how the materiality itself almost feels theatrical. What jumps out to you? Curator: The means of production are vital. Roerich wasn’t just creating an image; he was designing a material object to be reproduced, worn, and perceived within a theatrical performance. The Russian avant-garde were quite interested in blurring the boundaries between the fine arts and utilitarian art practices, like costume and set design. Can you see how the texture of the tempera, the specific pigments chosen, might speak to the practical considerations of costume production and use? Editor: That’s a fascinating point! I hadn’t considered the direct relationship between the *making* of the painting and the making of the costume. Do you mean how the broad strokes and vivid colors could translate to easily visible details on a stage? Curator: Precisely. Think about the labor involved. Someone had to source these materials, mix the paints, and then, imagine the costume makers trying to translate these painted textures into fabric and adornments. This wasn't just art for art's sake. How does the material quality affect your understanding of this work now? Editor: It shifts everything. I was initially focused on the image itself, the character… but thinking about it as a set of instructions, almost a pattern for creation...It really changes the emphasis to process, the people who brought it to life. Curator: Exactly. Recognizing the means of production re-centers our attention. Instead of only seeing a historical artwork, we start to understand the social network that surrounds art creation. It forces us to consider the art beyond the surface.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.